On September 29, 1639, the Red Bull players found themselves on the wrong side of the law. They’d recently performed The Whore New Vamped, whose author has since faded into obscurity. The play satirically alluded to the new duties on wine, which were instigated by Charles I but supported by few members of the Vintner’s Company of London. In a government statement, the players were accused of having “in a libellous manner traduced and personated some persons of quality and scandalised and defamed the whole procession of proctors belonging to the court of the civil law.”

Willam Abell

The New Whore Vamped pokes fun at William Abell, an alderman of London and Master of the Vintner’s Company of London. Abell spearheaded the effort to move the Vintner’s Company from an autonomous, self-governing entity to a royal monopoly. The move rankled not only Vintner’s members, but also members of the general public. This play would not be the first to call Abell to task; indeed, the war against Abell and his co-conspirators raged in print even before the infamous Long Parliament took up the issue.

An Influential and Privileged Organization

Though the exact date of the first English guild’s establishment is unknown, a number of livery companies had been established in London by the medieval period. People who practiced the same trade lived in the same area, and they often organized themselves to influence the market for their products and services. These groups had immense power: they influenced not only the economy and politics, but also social institutions and even religion. It’s no wonder, then, that the groups came to be known as guilds, a word that derives from the Anglo-Saxon word for “to pay.”

The Vintner’s Coat of Arms, circa 1633

The vintner’s guild seems to have been well established by the 1200’s; there was already record of “lawful merchants of London” fixing the price of wine. The Vintner’s Company received its first official charter on July 15, 1363. The charter was actually more like a grant of monopoly on trade with Gascony. A far-reaching document, the charter gave the guild duties of search and the right to buy cloth and herring to trade with the Gascons. Over the next century, wine would become vital to England’s economy. From 1446 to 1448, wine comprised almost a third of England’s entire import trade, and the Vintner’s Company was the eleventh most important of livery companies in London.

In the sixteenth century, the Vintner’s Company lost some of its prestige, along with its duties. Edward VI drastically limited the company’s country-wide right to sell wine in 1553. The company managed to regain some of its previous favor with the early Stuarts. Unfortunately a fateful alliance with Charles I would tarnish the Vintner Company’s reputation.

An Unsavory Arrangement with the King

When Abell took office as Master of the Vintner’s Company, the organization was a self-governing organization whose members oversaw all aspects of the wine business in London. But in June 1638, Willam Abell struck a deal with the king. He used the organization’s seal to sign a four-part indenture that transformed the Vintner’s Company into a royal monopoly. Under the contract, any profit or power derived from the wine trade went into a common “farm” that the company would purchase from Charles’ courtiers each year for the not-so-paltry sum of £57,000. While the arrangement might have been profitable for the company—and certainly for the king—many members saw it as far from ideal. As a royal monopoly, the organization was now much more susceptible to the whims of a monarch—and to transitions of power.

Then thanks to the Bishops’ Wars, Charles was forced to call Parliament to meet in 1640. He needed them to pass finance legislation to fund his war. But the MP’s hardly bent to the monarch’s wishes. They passed an act stating that the session of Parliament could not be dissolved until the members agreed to do so. They would not officially end the session until twenty years later, earning the nickname the Long Parliament. The Parliament moved to strip Charles I of the powers he’d accrued since ascending the throne, effectively ensuring that he would never again be an absolute ruler. They also freed everyone held in the Star Chamber and passed the Triennial Act of 1641, sometimes called the Dissolution Act, which stipulated that no more than three years would elapse between sessions of Parliament.

The Long Parliament also launched an investigation of Abell’s agreement with the king. They swiftly threw Abell and his co-conspirators in jail, but it took them ten months to work through the rest of the affair. In August 1641, Parliament took aggressive action, declaring forty importers delinquent for taking part in the wine contract. These merchants, too, were thrown in prison. Clearly Parliament stood not with the Crown-supported merchants, but with the city shopkeepers.

A War Waged with Pamphlets

Meanwhile on April 21, 1640, members of the Vintner’s Company had formed a committee to consider the wine sellers’ grievances with Abell’s contract. They made less than satisfactory progress, however, as the members could agree on little. Around this time, many vintners started refusing to pay tax on wine. And when Parliament convened, they delivered a petition without approval from company leaders.

All this time, a war was being waged with the printing press. From 1640 to 1642, countless pamphlets were printed by both Abell’s defenders and the Vintner’s Company. The Abell contingent claimed that the deal struck between Abell and the court represented the apotheosis of two years’ discussion among Vintner’s Company members. They said that the decision to become a royal monopoly had the full support of the membership, and had even passed when put to a vote.

Abell’s opponents claimed that Abell had achieved agreement only by threatening members with “many promises and persuasions,” some of which took the form of “divers and fearful threatenings.” By 1642, eminent parliamentary pamphlet printer Henry Parker had taken up the vintners’ cause, rushing to defend the company’s “own Reputation to the World.”

Cromwell Undermines the Company

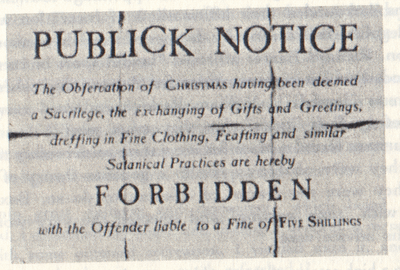

The Long Parliament would sit from 1640 to 1648, when the membership was purged by the New Model Army. Remaining members were called the Rump Parliament. When Oliver Cromwell effectively took complete control of England in 1653, he sent all the MP’s home. A Puritan, Cromwell believed that extraneous entertainments should be eliminated. Women could no longer wear make-up or colorful dresses. The theaters were shut down. Cromwell even outlawed Christmas.

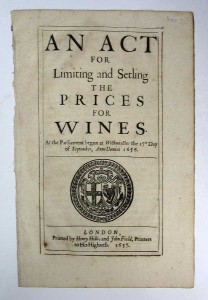

Though Cromwell’s rules were stringent, he did facilitate a number of important improvements, including stimulating the British economy. On September 17, 1656, Cromwell issued an Act for Limiting and Setling (sic) the Prices for Wines limiting the prices of Spanish and French wines. The act was a direct hit to the Vintner’s Company. Such a move from Cromwell should hardly surprise anyone; he actively and loudly supported the execution of Charles I and sought to undo as much damage from the former monarch as he possibly could. Charles II and James II similarly restricted the company’s influence. The Vintner’s Company took another hit with the Great Fire of London in 1666, when Company Hall and other properties were destroyed.

Though Cromwell’s rules were stringent, he did facilitate a number of important improvements, including stimulating the British economy. On September 17, 1656, Cromwell issued an Act for Limiting and Setling (sic) the Prices for Wines limiting the prices of Spanish and French wines. The act was a direct hit to the Vintner’s Company. Such a move from Cromwell should hardly surprise anyone; he actively and loudly supported the execution of Charles I and sought to undo as much damage from the former monarch as he possibly could. Charles II and James II similarly restricted the company’s influence. The Vintner’s Company took another hit with the Great Fire of London in 1666, when Company Hall and other properties were destroyed.

William and Mary restored some of the privileges that had been stripped away by their predecessors, but the Vintner’s Company would never regain its former dominance in the British wine trade. In 1725, the duty of search was finally abandoned, and membership dropped off. Yet the Vintner’s Company has survived to this day, a testament to the evolution of the wine trade.

The Abell-Kilvert controversy is merely one episode in the rich history of grape cultivation and wine making. Today there is little controversy over the statement that California has become one of the premier producers of quality wines. Next Tuesday Tavistock Books will issue a 40+ item FS list, with wine as its focus, and California looming large in this offering. Please watch for it.

Related Posts:

Au Paris: Food, Wine, and Rare Books!

Temperance, Prohibition, and the WCTU

George Cruikshank: “Modern Hogarth,” Teetotaler, and Philanderer

Thanks for reading! Love our blog? Subscribe via email (right sidebar) or sign up for our newsletter--you’ll never miss a post.