When Louisa May Alcott published Little Women in 1868, she immediately found the fame and fortune she’d sought since childhood. The legendary author is best remembered for this and other children’s books, but her true authorial passion was for writing cheap thrillers. Unbeknownst to most of her adoring readers, Alcott undertook her now classic novels only as a means to support her family. Indeed, Alcott has proven a much more complex individual than most of us would guess.

When Louisa May Alcott published Little Women in 1868, she immediately found the fame and fortune she’d sought since childhood. The legendary author is best remembered for this and other children’s books, but her true authorial passion was for writing cheap thrillers. Unbeknownst to most of her adoring readers, Alcott undertook her now classic novels only as a means to support her family. Indeed, Alcott has proven a much more complex individual than most of us would guess.

A Childhood of Privation

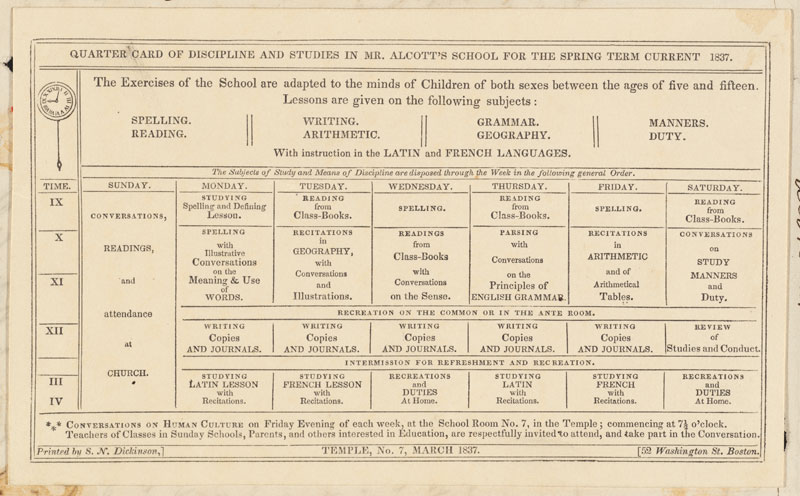

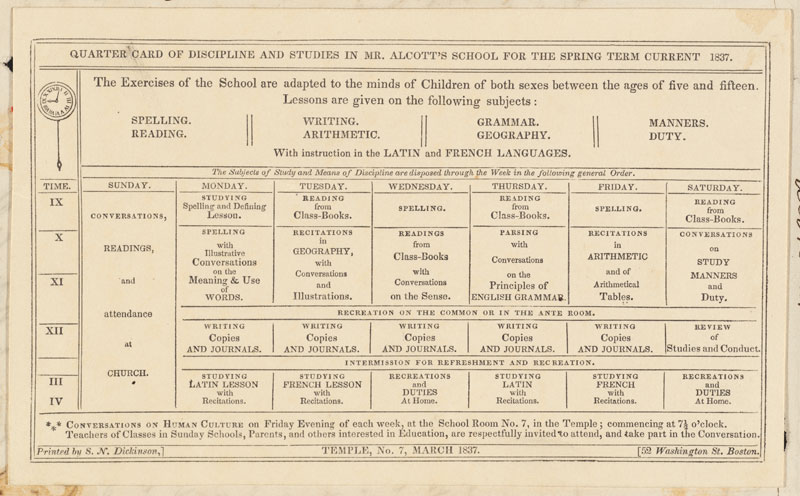

Born on November 29, 1832, Louisa May Alcott was the second of four daughters. Her mother, Abigail May Alcott, hailed from a distinguished Boston family. Her father, Amos Bronson Alcott, was a farmer who’d educated himself in philosophy. The members of the Alcott family were quite progressive for their time. In 1834, Bronson set up a school with a controversial co-ed curriculum. He managed to find students, but the community was soon turned off by his disciplinary tactics and frank discussion of religion. The final straw was when Bronson refused to dismiss a black student he’d admitted. White parents withdrew their children from the school, and Bronson was forced to shut down.

The progressive curriculum at Bronson Alcott’s Temple School

The family remained ardent abolitionists, participating in the Underground Railroad. When she was seven years old, Alcott opened an unused stove to discover a former slave hiding inside. The man was initially terrified that he’d been discovered, just as Alcott was frightened to find a man in the oven. Alcott taught the man to write his letters. This experience and others would eventually compel Alcott to serve in the Civil War so that she could contribute to ending slavery.

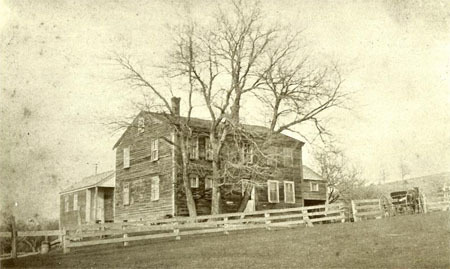

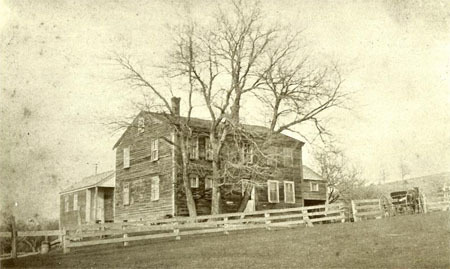

Among the family’s closest friends were Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau. Alcott grew up with their mentorship, studying in Emerson’s library and getting botany lessons from Thoreau. Despite this rich intellectual life, the Alcotts were quite poor. Bronson worked hard, but didn’t pay much attention to actually earning a living. His family often subsisted on nothing but bread and water, and they frequently moved–by the time they settled at Orchard House in 1858, the family had had around thirty temporary homes, and they could afford the home only with the support of relatives and Emerson, who wished Alcott’s sister Beth to pass her last days in comfort and security.

Fruitlands was strictly vegetarian. Residents were not even supposed to till the soil, as they might injure a worm.

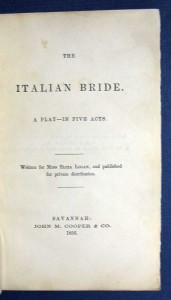

When Alcott was ten years old, the family undertook a radical experiment. Bronson co-founded the utopian community of Fruitlands with English reformer Charles Lane. Their goal was to survive without animal products or any commodities that had been generated by slavery, including coffee and tea. After only six months, the project had obviously failed. The Alcotts were completely destitute, and Bronson was on the brink of suicide. Alcott resolved that she would one day be rich and famous. At first she wanted to be an actress, and she soon began writing, directing, and acting in plays.

Early Financial Responsibility

Alcott began keeping a journal when she was eight years old, and she wrote her first novel at age seventeen. Heavily influenced by Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre, the novel would not be discovered and published until over a century later. Though Alcott wrote prolifically in her off time, she also worked hard as a teenager to help support her family. She had a series of jobs: teacher, governess, laundress, and even household servant. Her mother took work with an unemployment agency, and the family encountered women who had to take the roughest jobs. Moved by the plight of these illiterate immigrant and African American women, Alcott, her mother, and her sister Anna offered free reading and writing instruction.

Bronson, on the other hand, did little to support the family. He embarked on a long speaking tour–only to return with a single dollar in his pocket. The family, it seemed, would never escape poverty. The family’s dire straits gave Alcott a unique vantage point as a female author; most women writers of the era came from much more privileged backgrounds. It also hardened Alcott’s resolve “to turn my brains into money by stories.” In her early twenties, Alcott began writing romances for local papers. She rapidly learned how to tailor her writing for different markets and to experiment with different genres.

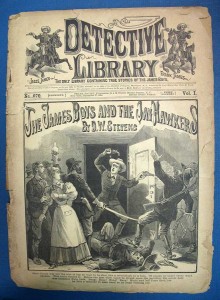

A Scandalous Little Writing Habit

Alcott also knew that writing such sensational stories would tarnish her own reputation, and she was not confident in the quality of her writing. She wrote these stories either anonymously or pseudonymously, thus protecting her own reputation. Harriet Reisen, author of Louisa May Alcott: The Woman Behind ‘Little Women,’ noted in an interview with NPR, “Louisa made herself a brand. She suppressed the fact that she had written pulp fiction that included stories about spies and transvestites and drug takers.”

It wasn’t until after her death that the full breadth of Alcott’s work was revealed. But Alcott found writing such potboilers quite thrilling, admitting that when she wrote them she slipped into a kind of “vortex” where time, food, and sleep simply didn’t exist. Scholars hypothesize that these stories were also an excellent outlet for Alcott, who never married and spent much time worrying about her family’s well-being.

Heeding the Call to Duty

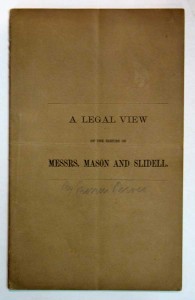

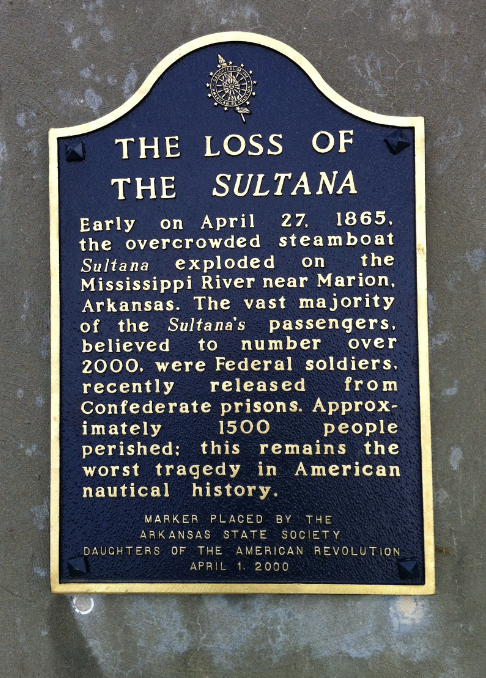

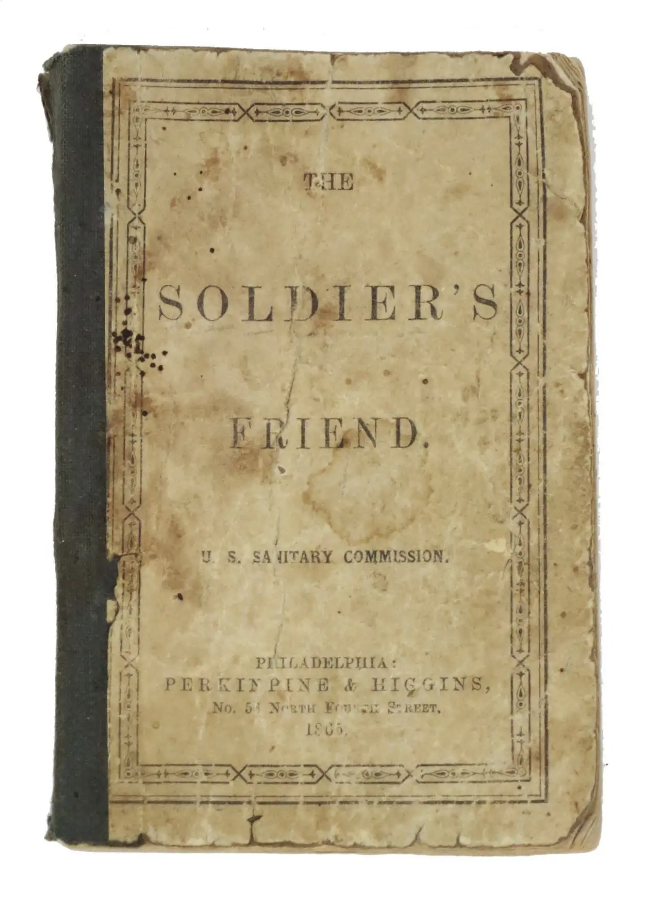

Then the Civil War broke out in 1861. Alcott reported to the Concord town hall, where she sewed uniforms and made bandages. As soon as she turned thirty, Alcott entreated family friend Dorothea Dix to let her become a field nurse even though she wasn’t married. Dix relented, and Alcott went to Washington, DC, where she ministered to soldiers after the Battle of Fredricksburg. Alcott fell prey to pneumonia and typhoid fever, cutting short her tenure as a nurse. Her treatment included doses of calomel, which contained mercury. It left Alcott weak and sickly for the rest of her life.

Unable to continue serving as a nurse, Alcott decided to support the war effort through her writing. She adapted her letters home into Hospital Sketches, and the book immediately became a bestseller. It represented a dramatic departure from Alcott’s other authorial endeavors–and it was published under her real name. The book’s success renewed Alcott’s confidence and resulted in new interest in her writing.

A Parisian Affair

Alcott had always wanted to travel, and in 1866, she had the opportunity to travel to Europe as a companion to an invalid. In Switzerland, she met Ladisas Wisniewski, a Polish freedom fighter who was thirteen years her junior. The pair managed to overcome the language barrier, passing a fortnight together in Paris. Cavorting with a twenty-year-old man without a chaperone certainly raised a few eyebrows, but Alcott dismissed the allegations of impropriety, pointing out that she was 33 years old.

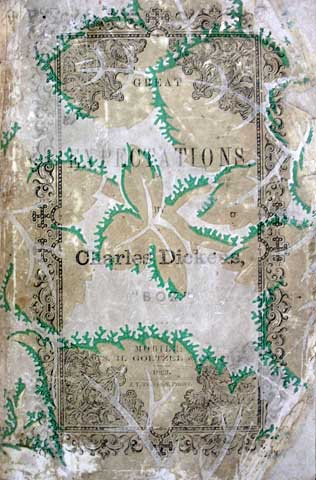

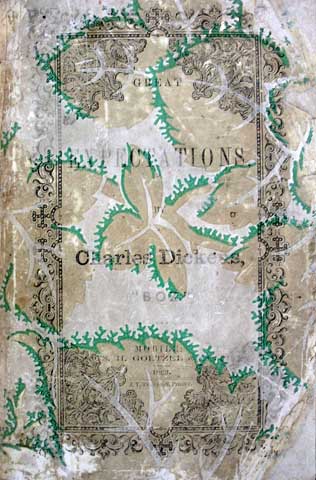

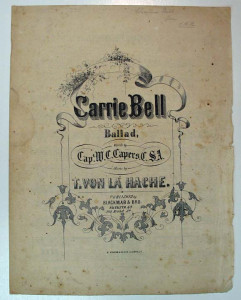

Alcott affectionately called Wisniewski “Laddie,” and he would be one of the inspirations for the character of Laurie in Little Women. The other was Alf Whitman, who was also much younger than Alcott. The two met at the Concord Dramatic Union (now the Concord Players), where they played Dolphus and Sophy Tetterby in Charles Dickens’ Haunted Man. Alcott doted on Whitman, and the two remained friends long after Whitman had married and had children. Alcott wrote to Whitman, “I put you in my story as one of the best and dearest lads I ever knew. ‘Laurie’ is you and my Polish boy [jointly].”

Challenging Gender Stereotypes

Though Alcott would have multiple ambiguous relationships with younger men, she claimed never to have loved them. In an 1883 interview with Louise Chandler Moulton, Alcott said, “I am more than half persuaded that I am a man’s soul, put by some freak of nature into a woman’s body…because I have fallen in love in my life with so many pretty girls and never once the least with any man.”

Alcott’s choice to remain a spinster was an unusual one for the time, even for a woman who had become a caregiver to her family. Yet Alcott had seen how dependent her mother had been on her father–and how poorly her father had provided for the family. “I’d rather be a spinster and paddle my own canoe,” she once wrote. That same sense of independence drove Alcott to campaign tirelessly for women’s suffrage. She attended the Woman’s Congress of 1875 in Syracuse, New York. In 1879, Alcott successfully campaigned for women’s suffrage in the election of the Concord school committee. The men of the town boycotted the vote, and Alcott was one of twenty women to cast a ballot.

Resigned to Writing “Moral Pap”

Alcott returned from Europe to find her family, predictably, in debt. Now able to “earn more from my pen than from my needle,” Alcott decided to write her way into fortune. She wrote in her journal in May, “Father saw Mr. Niles [of Roberts Brothers publishing house] about a fairy book. Mr. N wants a girls’ story, and I began Little Women. So I plod away, though I don’t enjoy this kind of thing. I never liked girls or knew many, except my sisters, but our queer plays and experiences may prove interesting.”

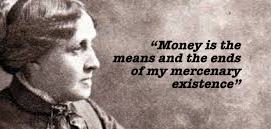

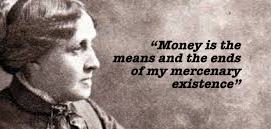

Alcott went about Little Women methodically over the course of a few weeks, with none of the joy she found in her thrillers. The first edition was published in 1868, when Alcott was 35 years old. It met with instant success, and Alcott’s fate as a writer was essentially sealed; she would build her career writing what she considered “moral pap for the young” because that’s what would support her family. Though Alcott was not upset to be “the goose that laid the golden egg,” she took a rather cynical view of her writing: “Money is the means and the ends of my mercenary existence.”

Because Little Women was so obviously based on Alcott’s own childhood, her family gained celebrity along with her. Bronson was quite fond of the attention. Now wealthy and widowed, he sported fine clothes and toured the country as “The Father of the Little Women.” He started publishing (very verbose) volumes of philosophy. Alcott built him the Concord School of Philosophy, so that he could again enjoy lecturing to an audience. His exploits were curtailed by a stroke, and he was forced to retire to a beautiful home in Louisburg Square, provided by his dutiful daughter, who visited almost every day. Alcott, however, wanted nothing to do with fame–perhaps because she saw so little merit in the books that had made her famous. Tourists shamelessly came calling at Orchard House, and Alcott would often pretend to be her own maid to avoid their attentions.

Because Little Women was so obviously based on Alcott’s own childhood, her family gained celebrity along with her. Bronson was quite fond of the attention. Now wealthy and widowed, he sported fine clothes and toured the country as “The Father of the Little Women.” He started publishing (very verbose) volumes of philosophy. Alcott built him the Concord School of Philosophy, so that he could again enjoy lecturing to an audience. His exploits were curtailed by a stroke, and he was forced to retire to a beautiful home in Louisburg Square, provided by his dutiful daughter, who visited almost every day. Alcott, however, wanted nothing to do with fame–perhaps because she saw so little merit in the books that had made her famous. Tourists shamelessly came calling at Orchard House, and Alcott would often pretend to be her own maid to avoid their attentions.

Then tragedy struck the Alcott family yet again. Alcott’s sister Anna Alcott Pratt had married into a wealthy family. While she was in Europe, her husband died unexpectedly, leaving her with two small children and no income. To ensure their financial comfort, Alcott again put pen to paper, this time writing Little Men. She assigned the royalties to her nephews, who would live with her until she passed away ten years later. When her sister May died in childbirth a few years later, Alcott took custody of the infant, who was named after her. Nicknamed “Lulu,” the child would call Alcott “Mother” and live with her until Alcott’s death.

When Alcott’s own health began to fail, she sought both traditional treatment and explored alternative medicine. In 1888, she went to a Roxbury convalescent home, convinced that proper rest would extend her longevity. That March, she visited her father for what she knew would be the last time. He passed away on March 4, 1888, and Alcott followed two days later.

Because Little Women was so obviously based on Alcott’s own childhood, her family gained celebrity along with her. Bronson was quite fond of the attention. Now wealthy and widowed, he sported fine clothes and toured the country as “The Father of the Little Women.” He started publishing (very verbose) volumes of philosophy. Alcott built him the Concord School of Philosophy, so that he could again enjoy lecturing to an audience. His exploits were curtailed by a stroke, and he was forced to retire to a beautiful home in Louisburg Square, provided by his dutiful daughter, who visited almost every day. Alcott, however, wanted nothing to do with fame–perhaps because she saw so little merit in the books that had made her famous. Tourists shamelessly came calling at Orchard House, and Alcott would often pretend to be her own maid to avoid their attentions.

Because Little Women was so obviously based on Alcott’s own childhood, her family gained celebrity along with her. Bronson was quite fond of the attention. Now wealthy and widowed, he sported fine clothes and toured the country as “The Father of the Little Women.” He started publishing (very verbose) volumes of philosophy. Alcott built him the Concord School of Philosophy, so that he could again enjoy lecturing to an audience. His exploits were curtailed by a stroke, and he was forced to retire to a beautiful home in Louisburg Square, provided by his dutiful daughter, who visited almost every day. Alcott, however, wanted nothing to do with fame–perhaps because she saw so little merit in the books that had made her famous. Tourists shamelessly came calling at Orchard House, and Alcott would often pretend to be her own maid to avoid their attentions.