By Margueritte Peterson

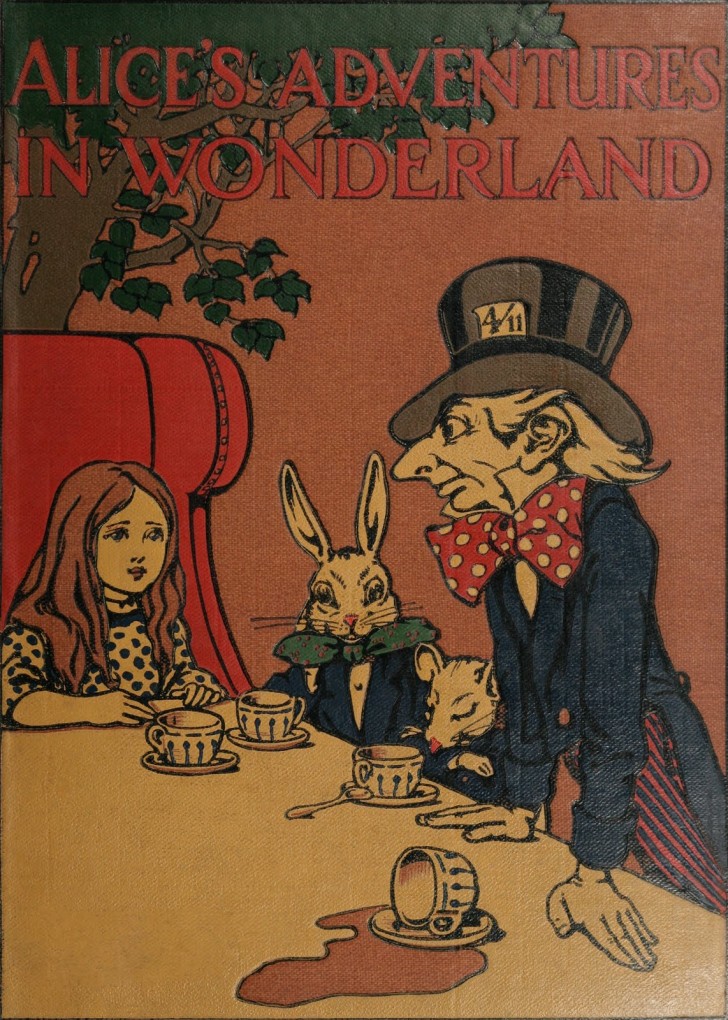

One of my most favorite Children’s writers of all time was born on the 27th of January, 1832. Scratch that – one of my most favorite writers, period, was born on the 27th of January, 1832. Many critics of great literature have commented on the fact that one of the most lasting kinds of literature is the kind that speaks to both children AND adults – writers whose works you can read when you are both 5 and 75 and learn something equally important at both of these starkly different ages. It is my super humble (though really awesome) opinion that the writer we honor today, on what would be his 184th birthday, is one of those writers. It is perhaps also appropriate that we honor his memory this week, as in less than a month there will be an ABAA Fair in Pasadena named after some of his most well-known work. The name of the fair? A Wonderland of Books. Can you guess who it is yet?

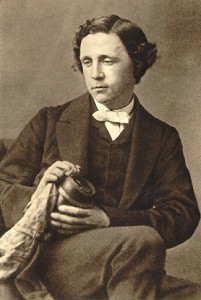

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (pen name Lewis Carroll – for those readers that are having one of those really slow days) was the fourth child of what would be a family of 12 (just children, that is). He and quite a few of his siblings would suffer from an unfortunate stammer for their lives, a condition often thought to be brought on when a naturally left-handed child is forced to become right-handed early in childhood (though there is no specific evidence that shows this to blame for Dodgson in particular). This stammer would cause the author no end of misery as he felt inferior throughout life and led to his later relationships with children (sparking great work and no end of controversy to this very day). A (somewhat vague) problematic time in Dodgson’s upbringing would arrive when the 13-year-old Dodgson was sent to Rugby School – an independent boarding school in Warwickshire. Years after leaving the school, Dodgson would write, “I cannot say … that any earthly considerations would induce me to go through my three years again … I can honestly say that if I could have been … secure from annoyance at night, the hardships of the daily life would have been comparative trifles to bear.” Though never expanded on, one can assume that Dodgson was either teased mercilessly or suffered even worse hardships at the hands of his fellow students.

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (pen name Lewis Carroll – for those readers that are having one of those really slow days) was the fourth child of what would be a family of 12 (just children, that is). He and quite a few of his siblings would suffer from an unfortunate stammer for their lives, a condition often thought to be brought on when a naturally left-handed child is forced to become right-handed early in childhood (though there is no specific evidence that shows this to blame for Dodgson in particular). This stammer would cause the author no end of misery as he felt inferior throughout life and led to his later relationships with children (sparking great work and no end of controversy to this very day). A (somewhat vague) problematic time in Dodgson’s upbringing would arrive when the 13-year-old Dodgson was sent to Rugby School – an independent boarding school in Warwickshire. Years after leaving the school, Dodgson would write, “I cannot say … that any earthly considerations would induce me to go through my three years again … I can honestly say that if I could have been … secure from annoyance at night, the hardships of the daily life would have been comparative trifles to bear.” Though never expanded on, one can assume that Dodgson was either teased mercilessly or suffered even worse hardships at the hands of his fellow students.

In 1850 Dodgson entered Christ Church College in Oxford, where he excelled academically, despite not always being the most faithful of students. He received first-class honors in Mathematics at the College, and continued teaching and studying the subject until 1855, when he won the Christ Church Mathematical Lectureship, a post he then held for the next 26 years. It was during this period that he began to be published nationally (having been writing poetry and satires, often humorous in nature, since young adulthood), in magazines like The Comic Times and The Train. It was during this period (1856, to be exact) that Dodgson first published a poem under the pseudonym “Lewis Carroll” – a work entitled “Solitude” published in the magazine mentioned above – The Train.

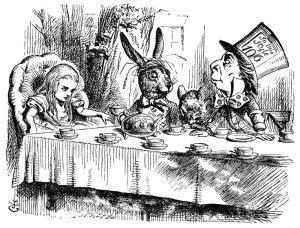

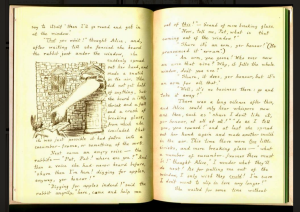

In the same year as the publication of “Solitude”, a new Dean arrived at Christ Church – Dean Henry Liddell. The Liddell family would feature heavily in Dodgson’s life for years to come, as he became an important influence and friend to the Liddell daughters – Lorina, Edith, and Alice. He would often take the Liddell children on short day-trips around Oxford – rowing or going for walks – and it was on one of these trips that he first began the story that would eventually turn into one of the most beloved children’s books of all time – Alice in Wonderland. His story of a precocious and questioning young girl was a story told to Alice Liddell, who in turn begged Dodgson to put it to paper for her. His personally illustrated manuscript entitled “Alice’s Adventures Under Ground” was completed in 1863. After Dodgson’s longtime friend (and fellow author) George MacDonald got ahold of the story, it was his persistence that led to its publication in 1865, with new illustrations by Sir John Tenniel. The book was an instant commercial success – with “Lewis Carroll” receiving attention from around the world.

In 1871 Dodgson published a sequel to Alice, titled “Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There”. Though it was popular as well, it’s somewhat darker mood and gloomier settings did not garner the same amount of success as the first novel. In 1876, “Carroll” published his next great work – a humorous and fantastical poem – “The Hunting of the Snark.” Another work came even later, in a two-volume set of a fairy story titled “Sylvie and Bruno” – though not as well known it has remained in print ever since.

A great love of Dodgson’s throughout his life was photography. The first photographs that are attributed to the author date back to 1856 – around the time that he began his association with the Liddell family. Often, even today, Dodgson comes under scrutiny when fans find out that over half of his photographic subjects include little girls – sometimes scantily clad in what one might consider strange positions or situations. Though no evidence has ever come into question of an inappropriate relationship between Dodgson and any of the girls he came into contact with (as most of his “friends” were children – Dodgson was notoriously shy around adults), many continue to wonder whether he ever considered a more intense relationship with the girls in the photographs. Nevertheless, they are interesting pieces of early photographic work – all done with full knowledge of the subject’s parents and often commissioned by the families themselves!

Dodgson is well-remembered for Alice and for the children’s stories he came up with, but it should be noted that this Mathematician also produced works that are still remembered if not used today in Mathematical sciences. He published almost a dozen books under his real name (not the pseudonym) on the science, and himself developed new ideas in the subject of linear algebra. He taught Mathematics in his post at Christ Church until 1881, and then remained in residence there for the rest of his life. On January 14th, 1898, two weeks away from his 66th birthday, Dodgson passed away from pneumonia following a bout of influenza, and is buried in Guildford. One thing is for sure and certain, whether you wish to remember him as Charles Dodgson or Lewis Carroll – this author remains, to this day, one of the most well-known names in Children’s Literature (if not the most well-known), and deserves to be celebrated on this his 184th birthday!

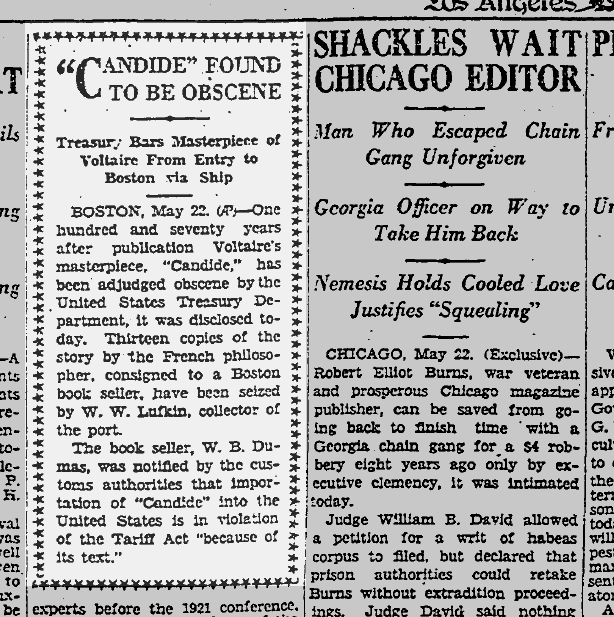

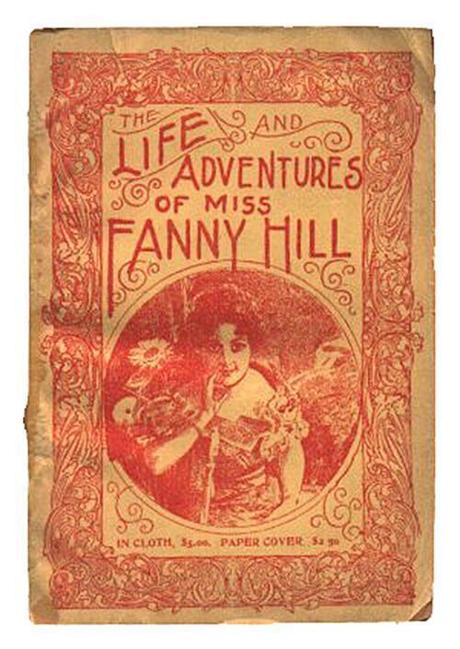

Considered the first pornographic novel published in English, Fanny Hill is every bit as lurid as one would expect from the fictional memoir of a Georgian prostitute. Even more scandalous: the eponymous protagonist enjoys the work of earning “profit by pleasing.” Author John Cleland and the book’s original publisher were immediately thrown into jail after the book was published. And in America, Fanny Hill was the subject of the country’s very first obscenity trial: in 1821, two men were charged with printing an illustrated version. That edition and subsequent contraband editions became hot collector’s items; even Benjamin Franklin was said to have a copy. The book found its way back to the US Supreme Court in 1963 after Massachusetts banned the book. The Supreme Court found the book lewd–and ruled that it was protected by the First Amendment.

Considered the first pornographic novel published in English, Fanny Hill is every bit as lurid as one would expect from the fictional memoir of a Georgian prostitute. Even more scandalous: the eponymous protagonist enjoys the work of earning “profit by pleasing.” Author John Cleland and the book’s original publisher were immediately thrown into jail after the book was published. And in America, Fanny Hill was the subject of the country’s very first obscenity trial: in 1821, two men were charged with printing an illustrated version. That edition and subsequent contraband editions became hot collector’s items; even Benjamin Franklin was said to have a copy. The book found its way back to the US Supreme Court in 1963 after Massachusetts banned the book. The Supreme Court found the book lewd–and ruled that it was protected by the First Amendment.