By Margueritte Peterson

If someone says “Children’s Books” to you, what is the first thing that comes to your mind? Picture books? Perhaps here is the better question… what author first comes to mind? I would venture to bet that at least 90% of you come up with the same name. However, did you know that the name you come up with is not his true name? (Probably most of you do, since you are members of the book world or bibliophiles and would know something like that… but humor me!)

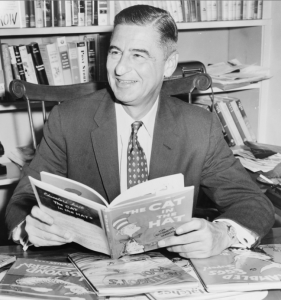

Theodor Seuss Geisel was born on March 2nd, 1904 to a German family in Springfield, Massachusetts. His father ran a family-owned brewery in Massachusetts (well, until the Prohibition did away with that). Geisel went to school in Massachusetts until he went to Dartmouth College in New Hampshire, graduating in 1925. During his time at Dartmouth, Geisel first showed skill and interest in humorous literature as rose to the role of editor-in-chief of the literary magazine the Dartmouth Jack-O-Lantern before graduating. Unfortunately, one college incident threatened to end his early literary career – when Geisel was caught drinking gin (the Prohibition was in effect) in his dorm room with some of his friends. In punishment for this crime, Geisel was forced to resign from his position at the magazine. In order to continue publishing his work at the Jack-O-Lantern, Geisel began writing under the pen name “Seuss”, his middle name. The beginning of Dr. Seuss was underway.

Theodor Seuss Geisel was born on March 2nd, 1904 to a German family in Springfield, Massachusetts. His father ran a family-owned brewery in Massachusetts (well, until the Prohibition did away with that). Geisel went to school in Massachusetts until he went to Dartmouth College in New Hampshire, graduating in 1925. During his time at Dartmouth, Geisel first showed skill and interest in humorous literature as rose to the role of editor-in-chief of the literary magazine the Dartmouth Jack-O-Lantern before graduating. Unfortunately, one college incident threatened to end his early literary career – when Geisel was caught drinking gin (the Prohibition was in effect) in his dorm room with some of his friends. In punishment for this crime, Geisel was forced to resign from his position at the magazine. In order to continue publishing his work at the Jack-O-Lantern, Geisel began writing under the pen name “Seuss”, his middle name. The beginning of Dr. Seuss was underway.

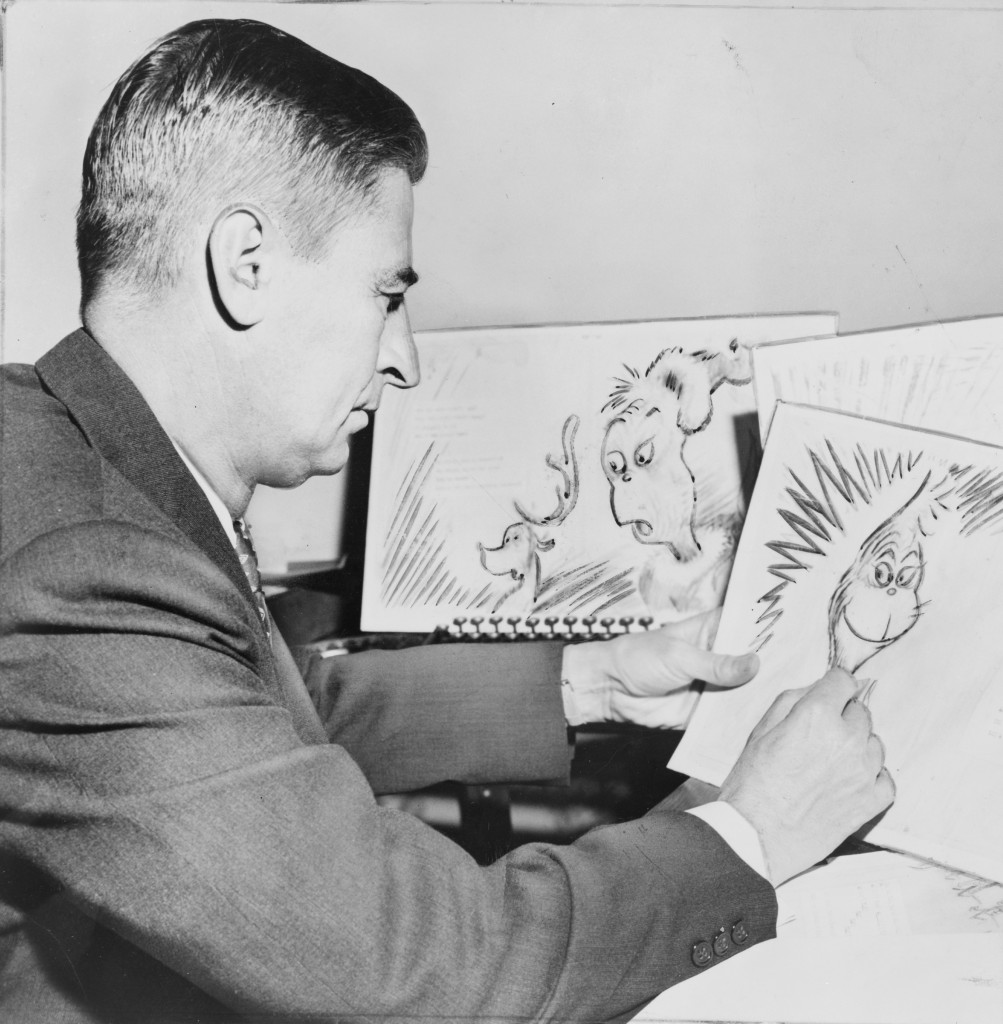

Once graduating from Dartmouth, Geisel began his PhD studies at Lincoln College, Oxford, to earn a degree in English Literature. Though he left Oxford without a degree in early 1927, Geisel was still able to begin his living publishing humorous cartoons. He accepted a job at the humor magazine Judge and 6 months after he began working at the magazine he first published work under his pen-name “Dr. Seuss.” Geisel’s cartoons gained popularity throughout the end of the 1920s and the entirety of the 1930s, largely due to his help with advertisements of popular brands like General Electric and Standard Oil – adverts that helped him and his wife maintain financial stability through the Great Depression. Due to help from a friend (despite his popularity), Geisel was able to begin publishing humorous poems with the Vanguard Press. In 1940, he published a poem under the title “Horton Hatches an Egg” – a poem that has, to this day, sparked further books, movies, animated films and even musical productions.

Our inscribed copy of Bartholomew and the Oobleck can be found here!

Throughout the 1940s and WWII, Geisel created hundreds of political cartoons criticizing Hitler and Mussolini and strongly supported the US war effort. Shortly after the war, Geisel and his wife Helen moved from New York to La Jolla, California and he returned to writing children’s books. Between 1950 and 1960 Geisel published many of the works he is most well-known for today, such as Bartholomew and the Ooblek (1949), If I Ran the Zoo (1950), Horton Hears a Who! (1955 – a more in-depth work on his original poem), If I Ran the Circus (1956), The Cat in the Hat (1957), How the Grinch Stole Christmas (1957) and Green Eggs and Ham (1960). In 1954, William Ellsworth Spaulding challenged Geisel to write a book with 250 words chosen by the education division of Houghton Mifflin of words that all 1st graders ought to know. The result contained 236 of the 250 words and was Geisel’s famed The Cat in the Hat!

Though Geisel (surprisingly) never won a Newbery or Caldecott award, he was awarded an honorary doctorate from Dartmouth (1956), a Laura Ingalls Wilder Medal in 1980, and the Pulitzer Prize in 1984 (for his “substantial and lasting contributions to children’s literature”). Geisel also never had children of his own (perhaps he was too busy teaching and entertaining everyone else’s children!), but will forever be remembered as one of the fathers of Children’s Literature!

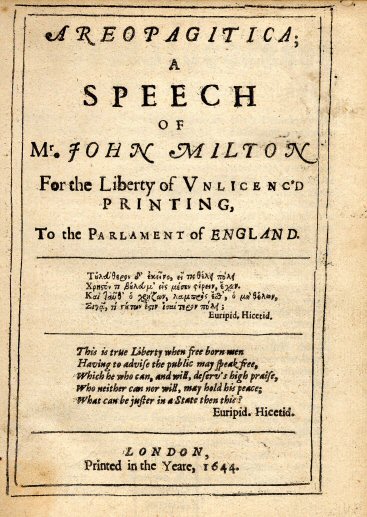

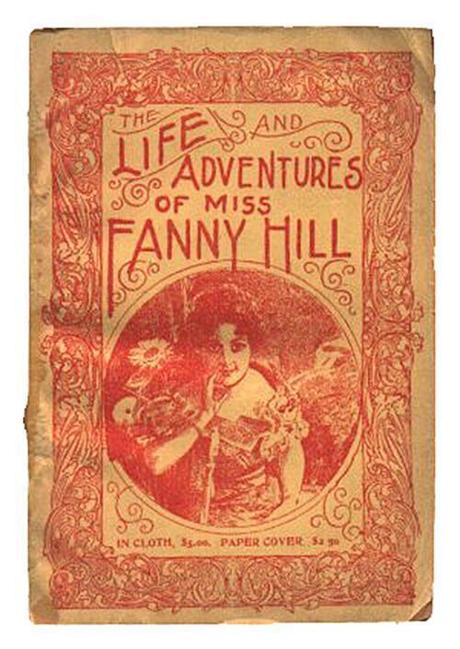

Considered the first pornographic novel published in English, Fanny Hill is every bit as lurid as one would expect from the fictional memoir of a Georgian prostitute. Even more scandalous: the eponymous protagonist enjoys the work of earning “profit by pleasing.” Author John Cleland and the book’s original publisher were immediately thrown into jail after the book was published. And in America, Fanny Hill was the subject of the country’s very first obscenity trial: in 1821, two men were charged with printing an illustrated version. That edition and subsequent contraband editions became hot collector’s items; even Benjamin Franklin was said to have a copy. The book found its way back to the US Supreme Court in 1963 after Massachusetts banned the book. The Supreme Court found the book lewd–and ruled that it was protected by the First Amendment.

Considered the first pornographic novel published in English, Fanny Hill is every bit as lurid as one would expect from the fictional memoir of a Georgian prostitute. Even more scandalous: the eponymous protagonist enjoys the work of earning “profit by pleasing.” Author John Cleland and the book’s original publisher were immediately thrown into jail after the book was published. And in America, Fanny Hill was the subject of the country’s very first obscenity trial: in 1821, two men were charged with printing an illustrated version. That edition and subsequent contraband editions became hot collector’s items; even Benjamin Franklin was said to have a copy. The book found its way back to the US Supreme Court in 1963 after Massachusetts banned the book. The Supreme Court found the book lewd–and ruled that it was protected by the First Amendment.