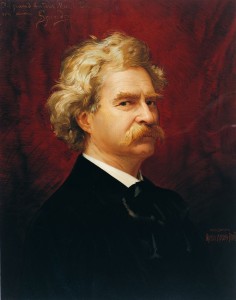

On February 13, 1991, Sotheby’s made an incredible announcement: the auction house had Mark Twain’s long-lost manuscript of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. The manuscript bore edits in Twain’s own hand and had scenes not included in the published novel. The discovery and subsequent authentication sparked an argument over who had rights to the manuscript.

On February 13, 1991, Sotheby’s made an incredible announcement: the auction house had Mark Twain’s long-lost manuscript of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. The manuscript bore edits in Twain’s own hand and had scenes not included in the published novel. The discovery and subsequent authentication sparked an argument over who had rights to the manuscript.

The recovered manuscript was unearthed in a set of trunks sent to a Los Angeles librarian after her aunt, a resident of upstate New York where Twain once lived, passed away. It constitutes the first half of the Huckleberry Finn manuscript. The second half had been in the possession of the librarian’s grandfather James Gluck. Gluck had solicited the manuscript directly from Twain for the Buffalo and Erie Library. At the time, Twain had been unable to find the first half of the manuscript, and it was presumed lost.

A “custody battle” ensued among the librarian and her sister; the library; and the Mark Twain Papers Project in Berkeley, California. They finally agreed that the library would take the papers, but that all three would share publication rights. The manuscript was published by Random House in 1995.

The discovery of such a document generates excitement among scholars and rare book collectors alike. The Huckleberry Finn manuscript was but one of many such documents to turn up unexpectedly.

Corroborating Robert Hooke’s Claim to an Invention

Revered scientist Robert Hooke was one of the original fellows of the Royal Society and the curator of the group’s experiments. He was also responsible for recording the organization’s minutes from 1661 to 1682. The minutes make for fascinating reading, not least because of Hooke’s own asides and commentary. They recount many seminal moments in science, including the earliest work with a microscope and the first sightings of sperm and micro-organisms. This fascinating 500-page document didn’t show up until 2006, when it was discovered in a dusty cabinet.

Revered scientist Robert Hooke was one of the original fellows of the Royal Society and the curator of the group’s experiments. He was also responsible for recording the organization’s minutes from 1661 to 1682. The minutes make for fascinating reading, not least because of Hooke’s own asides and commentary. They recount many seminal moments in science, including the earliest work with a microscope and the first sightings of sperm and micro-organisms. This fascinating 500-page document didn’t show up until 2006, when it was discovered in a dusty cabinet.

The minutes from December 1679 detail correspondence between Hooke and Sir Isaac Newton regarding the design of an experiment to confirm the rotation of the earth. Hooke recorded a suggestion from Sir Christopher Wren, which required shooting bullets into the air at precise angles to see if they fell in a circle. But perhaps even more interesting is that the document finally elucidates a feud between Hooke and Dutch physicist Chistiaan Huygens.

Huygens announced that he’d invented a watch that would keep its own time for several days and would make it possible to measure longitude, which infuriated Hooke. He claimed that he’d showed the Royal Society the same invention five years earlier, and that someone must have leaked the design. Hooke embarked on a mission to prove he’d invented the watch first. He painstakingly combed through years of Royal Society minutes, looking for proof of his own invention. Ironically, he’d ripped out the notes about the invention itself and taken them home for safekeeping–only to misplace them. In this newly discovered document, Hooke exonerates himself: he records a quote from his predecessor, Henry Oldenberg, about Hooke’s presentation of the invention–five years earlier than Huygens, just as Hooke had alleged.

A First Look at Yellowstone

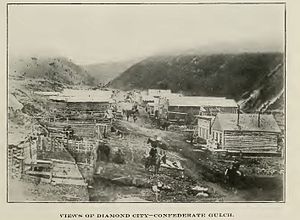

By 1869, prospectors’ accounts of their finds at the Diamond City gold camp were both outlandish and persistent. Incredulous, thirty-year-old mining engineer David E Folsom decided to investigate for himself. In September of 1869, he undertook a treacherous expedition with friends Charles Cook and William Peterson. The group’s military envoy had canceled, and other would-be adventurers backed out, unwilling to venture into hostile territory unescorted.

During the four-week expedition, the group witnessed and documented the natural wonders of the area. They also took numerous measurements of the land, even using a rock on a string to measure the height of waterfalls. Folsom recorded their experiences and tried to sell his account to a number of prominent national magazines. They all turned him down because the tales seemed too fantastic to be real. Finally a small Chicago paper called Western Monthly ran the story. Folsom’s account contributed to the deployment of both the Washburn-Doane-Langford expedition (1870) and the Hayden expedition (1871)–which subsequently led Congress to make Yellowstone the first national park.

Folsom’s great-grandson David A Folsom found the original manuscript, written in pencil on lined paper. Two other manuscript copies had been destroyed in two separate fires, and had previously been the only extant copies. The younger Folsom gave the manuscript to Montana State University’s Renne Library Special Collections, where it still resides today.

Truman Capote, Kathryn Graham, and a Little Hashish

Ever the journalist, Truman Capote wasn’t known for glossing over his acquaintances’ secrets (or character flaws). Many a New York socialite fell victim to his pen–with one notable exception. Kathryn Graham never seemed to appear in Capote’s work. That all changed with the discovery of an unpublished story, “Yachts and Things” among Capote’s papers at the New York Public Library.

In the story, the narrator (presumably Capote) recounts a cruise along the Turkish coast with a “distinguished” and “intellectual” woman called Mrs. Williams. Their hosts have been called away due to a death in the family, and another guest has just passed away. One evening, the two invite some Turks aboard and smoke hashish for the first time. Though the hosts aren’t named, the deceased companion is named Adlai Stevenson.The researchers who discovered the story conjectured that the woman in the story was actually Graham because of her well-documented relationship with Stevenson, and they didn’t do much further research.

But a look at Graham’s own autobiography, Personal History, yields a more definitive answer. Graham, Capote, and Stevenson were invited on the trip by Gianna and Marcella Agnelli, who were unable to join their guests because of a death in the family. Graham and Capote stopped in London, and Graham coyly tells how Stevenson stayed with her (and forgot his tie and glasses in the morning). Stevenson died of a heart attack the next day. Graham and Capote decided to go on the cruise anyway, and Graham says they passed the time discussing Capote’s soon-to-be-published In Cold Blood.

Manuscripts like these will always be beloved because they seem to offer us a greater intimacy with the author. They illustrate the author’s own writing process, essentially illuminating the process of creating great history and literature.

Related Posts:

Three Pioneering Authors Who Used Pseudonyms

Thanks for reading! Love our blog? Subscribe via email (right sidebar) or sign up for our newsletter--you’ll never miss a post.