“Hope is the thing with feathers” by Emily Dickinson is the first poem I remember reading and analyzing as part of a school assignment.

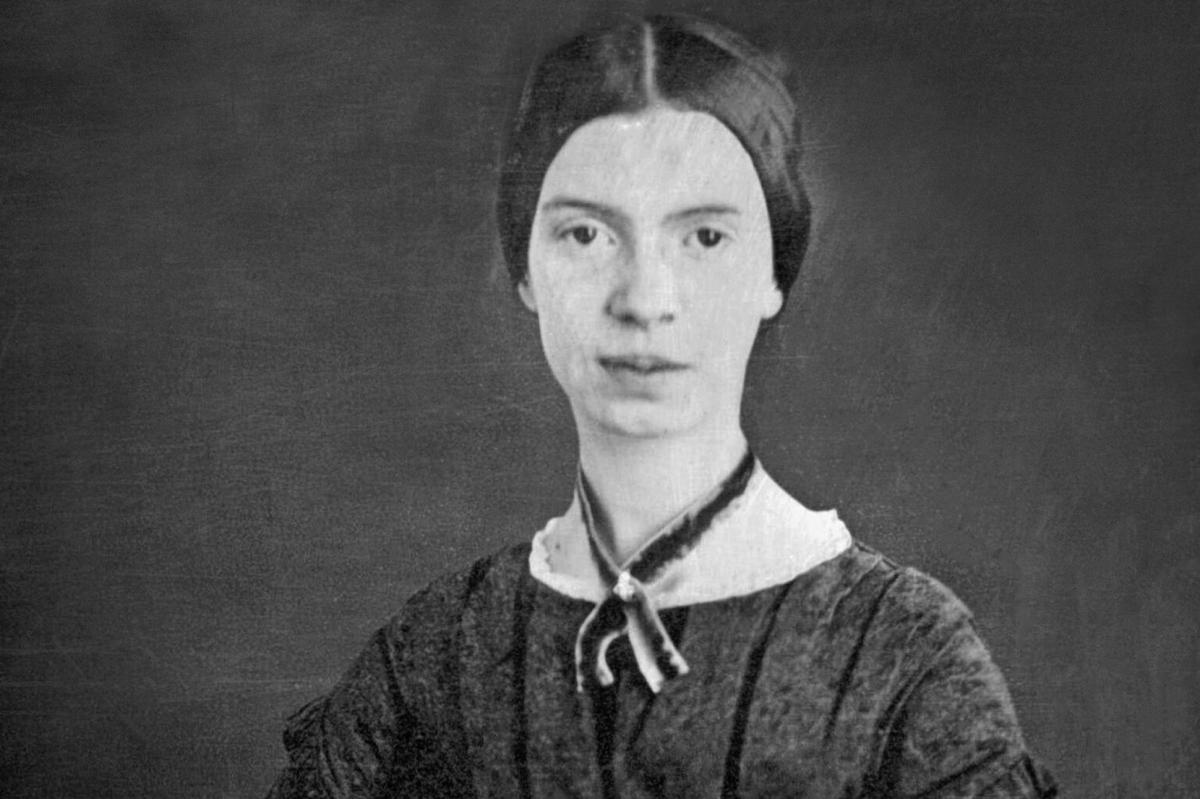

The first time I read it, I definitely did not “get it”. I honest to goodness remember my initial reaction to my teachers’ analysis of the poem itself. It was the first time I asked myself the question… how do we know that that is what the author wanted us to read into it? How do we know for sure that she meant for the bird to signify the innocence of the emotion of hope? With some authors it is harder than others – as some authors left… well… less of a trail of breadcrumbs for us to follow. One of those authors was Emily Dickinson – the recluse who, to this day, inspires many with her words, whilst we know relatively little about her innermost thoughts during her most productive literary period. On today the anniversary of her death, we’d like to give a brief background on this interesting poet and focus not on exactly what her words mean to us, but rather on the lasting legacy she left behind.

Emily Dickinson was born in Amherst, Massachusetts, on December 10th, 1830. She was the second of three children, with one elder brother named Austin and a younger sister, Lavinia. Her father was not only a lawyer by trade, but a trustee of Amherst College, where his father had been one of the founders of the school. With their background in education, the Dickinson children were given a thorough education for the time, certainly when it came to the two girls. At the age of 10 Emily and her sister began their studies at Amherst Academy, which had begun to allow female students a scant two years before their studies began. Emily remained at the school for seven years, studying math, literature, latin, botany, history, and all manner of respected academia. Upon finishing her studies at the Academy in 1847, Dickinson enrolled in the Mount Holyoke Female Seminary (now Mount Holyoke College). Although the Seminary was only 10 miles from her home, Dickinson only remained at the school for 10 months before returning home – for reasons many have tried to unearth but none can be sure of.

Emily Dickinson was born in Amherst, Massachusetts, on December 10th, 1830. She was the second of three children, with one elder brother named Austin and a younger sister, Lavinia. Her father was not only a lawyer by trade, but a trustee of Amherst College, where his father had been one of the founders of the school. With their background in education, the Dickinson children were given a thorough education for the time, certainly when it came to the two girls. At the age of 10 Emily and her sister began their studies at Amherst Academy, which had begun to allow female students a scant two years before their studies began. Emily remained at the school for seven years, studying math, literature, latin, botany, history, and all manner of respected academia. Upon finishing her studies at the Academy in 1847, Dickinson enrolled in the Mount Holyoke Female Seminary (now Mount Holyoke College). Although the Seminary was only 10 miles from her home, Dickinson only remained at the school for 10 months before returning home – for reasons many have tried to unearth but none can be sure of.

Though throughout her late teens Dickinson seemed to enjoy life in Amherst socially, and was certainly already writing poetry (a family friend Benjamin Franklin Newton hinted in letters before his death in this time that he had hoped to live to see her reach the success he knew possible), by her twenties Emily was already feeling a melancholy pull, exacerbated by her emotions when it came to death, and the deaths of those around her. Her mother’s many chronic illnesses kept Emily often at home, and by the 1860s (Dickinson’s 30s) she had already largely pulled out of the public eye. By her 40s, Dickinson rarely left her room, and preferred to speak with visitors through her door rather than face-to-face. Unbeknownst to any, Dickinson worked tirelessly throughout this period on her poetry, and by the end of her life had amassed a collection of roughly 1,800 poems neatly written in hand sewn journals. That being said, less than one dozen of her poems would be published during her lifetime. The first book of her poetry, published four years after her death on May 15th, 1886 by her sister Lavinia, was a resounding success. In less than two years, eleven editions of the first book had been printed, and her words spread across nations.

Though throughout her late teens Dickinson seemed to enjoy life in Amherst socially, and was certainly already writing poetry (a family friend Benjamin Franklin Newton hinted in letters before his death in this time that he had hoped to live to see her reach the success he knew possible), by her twenties Emily was already feeling a melancholy pull, exacerbated by her emotions when it came to death, and the deaths of those around her. Her mother’s many chronic illnesses kept Emily often at home, and by the 1860s (Dickinson’s 30s) she had already largely pulled out of the public eye. By her 40s, Dickinson rarely left her room, and preferred to speak with visitors through her door rather than face-to-face. Unbeknownst to any, Dickinson worked tirelessly throughout this period on her poetry, and by the end of her life had amassed a collection of roughly 1,800 poems neatly written in hand sewn journals. That being said, less than one dozen of her poems would be published during her lifetime. The first book of her poetry, published four years after her death on May 15th, 1886 by her sister Lavinia, was a resounding success. In less than two years, eleven editions of the first book had been printed, and her words spread across nations.

It is only now, in researching her life and rereading a few of her best-loved poems that I can see the answer to my question of long ago. We don’t know what Emily Dickinson wanted each word to signify. We don’t need to know. It is the way her poetry made and makes the public feel that gave it the popularity it still holds to this day. “Hope”, indeed.

Today we honor Emily Dickinson and her lasting impact on the world of poetry.

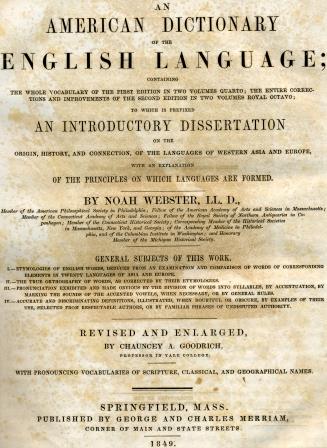

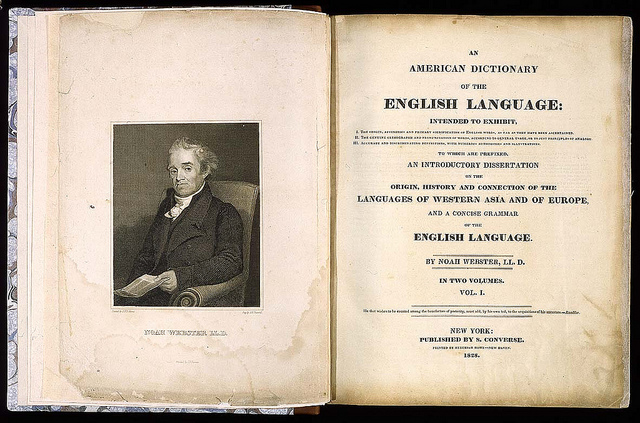

Webster married Rebecca Greenleaf in 1789, and as she was of good breeding (man, I don’t get to use that phrase often enough) he was able to join higher levels of society in Connecticut than he had been. (They would later have 8 children, but that is neither here nor there.) Due to his beliefs in the revolution and conviction in America’s greatness, one Alexander Hamilton loaned him $1,500 in 1793 to move to New York and become the editor for the Federalist Papers. For the next few decades, Webster spent much of his time being one of the most profuse authors of the time, especially when it came to political reports, but also in regard to textbooks and articles across the board.

Webster married Rebecca Greenleaf in 1789, and as she was of good breeding (man, I don’t get to use that phrase often enough) he was able to join higher levels of society in Connecticut than he had been. (They would later have 8 children, but that is neither here nor there.) Due to his beliefs in the revolution and conviction in America’s greatness, one Alexander Hamilton loaned him $1,500 in 1793 to move to New York and become the editor for the Federalist Papers. For the next few decades, Webster spent much of his time being one of the most profuse authors of the time, especially when it came to political reports, but also in regard to textbooks and articles across the board.

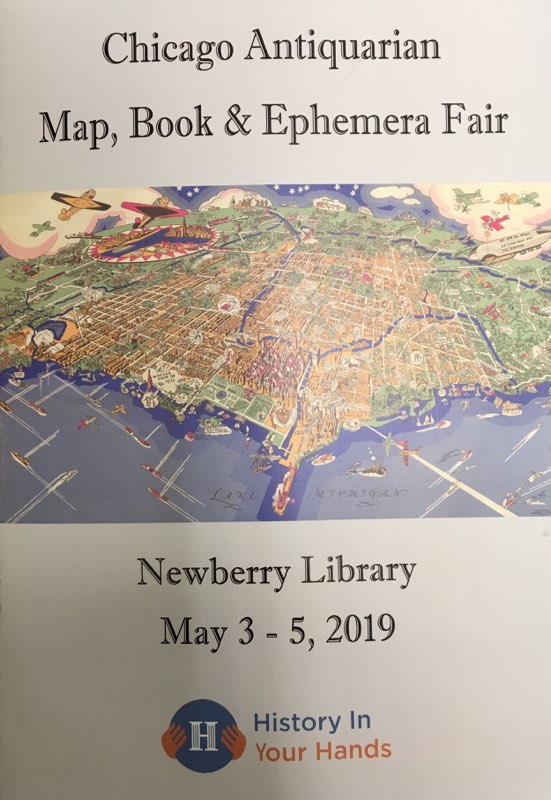

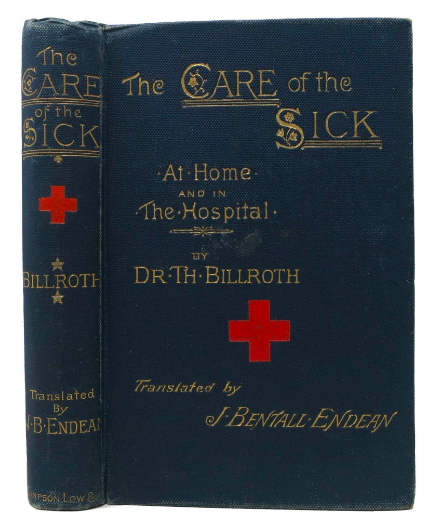

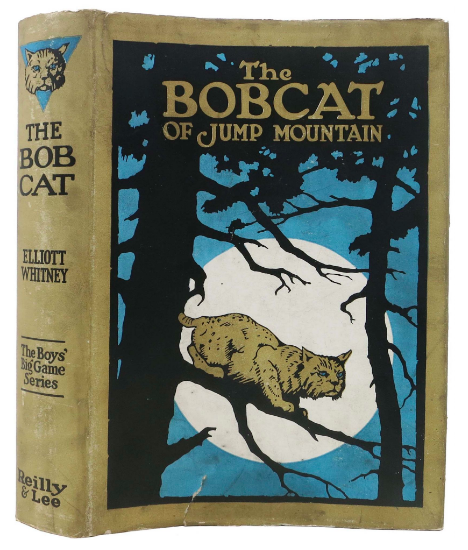

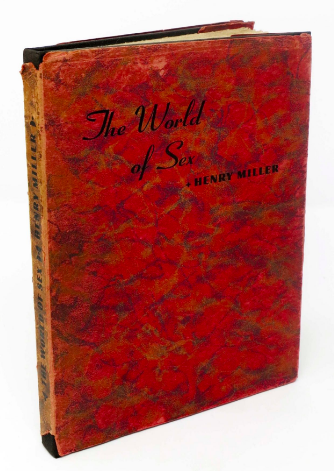

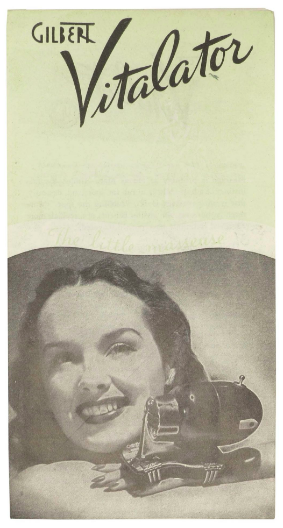

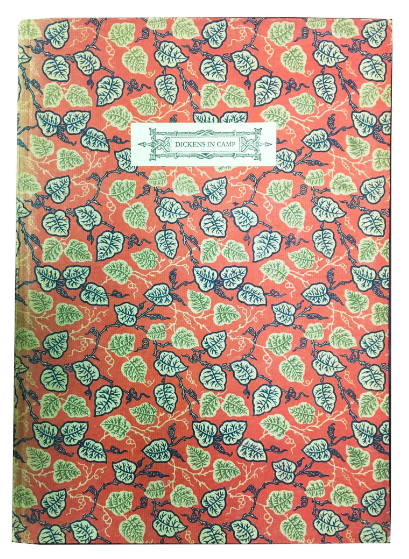

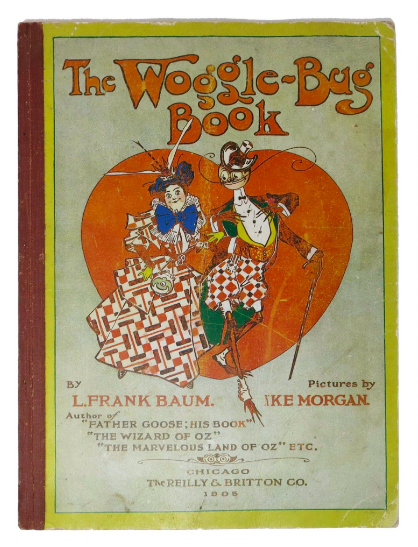

Now, we might be exaggerating just a teensy bit, as there really wasn’t any rain falling on our books, as we were able to unload in the garage, with plenty of help with dollys, unlike other local fairs we have attended! Luckily for us… it meant we didn’t really need to do much heavy lifting. The fair itself was a fun event, us getting to catch up with a lot of our fellow bibliophiles before the Oakland fair this upcoming weekend, and although the sales were a tad underwhelming for us (in all fairness, however, we were saving our big ticket items for the upcoming Oakland fair), it was definitely worth the trip in acquisitions – many of which you’ll be able to see on display at the Marriott this weekend! That all being said, many booksellers did have great sales… with one rumor that a seller sold out his entire booth!

Now, we might be exaggerating just a teensy bit, as there really wasn’t any rain falling on our books, as we were able to unload in the garage, with plenty of help with dollys, unlike other local fairs we have attended! Luckily for us… it meant we didn’t really need to do much heavy lifting. The fair itself was a fun event, us getting to catch up with a lot of our fellow bibliophiles before the Oakland fair this upcoming weekend, and although the sales were a tad underwhelming for us (in all fairness, however, we were saving our big ticket items for the upcoming Oakland fair), it was definitely worth the trip in acquisitions – many of which you’ll be able to see on display at the Marriott this weekend! That all being said, many booksellers did have great sales… with one rumor that a seller sold out his entire booth!