by Vic Zoschak, Jr.

Dinner at Roxy’s could tempt us all!

Reading colleagues’ comments with regard to the recent Brooklyn event, allow me to put in a plug for the Sacramento Antiquarian Fair, held this past weekend. A semi-annual event, hosted by Jim Kay, I suspect it doesn’t have the panache of Brooklyn, but that said, it has come to be beloved by those of us on the west coast, drawing exhibitors from both ends of the coast, not to mention a fellow bookseller who routinely makes the trek from out Utah way… that said, despite the close proximity of Sacramento, I suspect David flew east for the weekend, for the local event definitely has a Californiana bias in exhibitor offerings, and that not David’s metier ime, but it is one of mine. Given that, from an ABAA colleague I bought a [what I consider to be] fantastic item: an 1853 Sacramento Directory, and as I recall, the second Sacramento city directory ever published, this one an inscribed presentation copy from the publisher to the man considered to be Sacramento’s first mayor. Plus *bunches* of other neat stuff, filling over two boxes, and occasioning Samm’s questioning look: “How the heck are we going to get all this stuff in the car?!?”

I have no doubt the food & beverage choices in Brooklyn are myriad, however, I’d stack up the fair’s local concession’s Chicken Pesto sandwich against any comer offered elsewhere [Taylor, feel free to offer your thoughts here 😉 ]. And the pre-fair, post-setup Friday night dinner at Roxy has become traditional, this time around, shared with 9 colleagues… Chuck, Roxy’s Manhattan might even tempt you.

So, it seems we have two credible regional events on this same weekend in September, and for that I’m thankful. Here on the West Coast, we’ve lost so many regional fairs over the last decade or two that it’s gratifying this one is thriving [I understand a new fair attendance record was set yesterday]. Further, Jim tells us it’s here to stay as long as he is. I should add, it’s relatively inexpensive to exhibit… my half-booth, with display case, was a modest $385.

Finally, I personally like the fact that the Sacramento show is a one day event. I got home last night by 7 pm, slept in my own bed, and today, get to watch Jimmy G & cast take on the Vikings… in other words, no standing around in the booth on a quiet Sunday, hands in pockets, watching the clock sloooowly make its way towards 5 pm.

Very civilized, promoters please take note.

V.

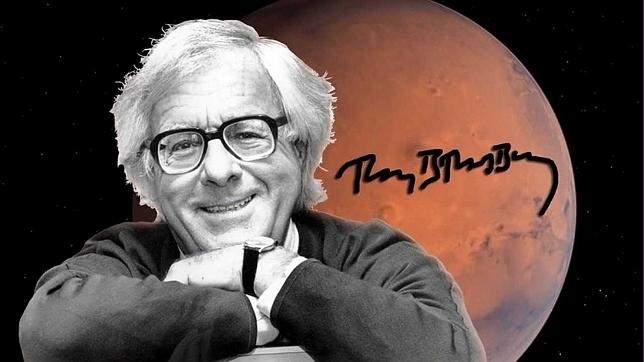

Bradbury was born on August 22nd, 1920, in rural Illinois. In 1932 at the age of twelve, Bradbury had a somewhat extraordinary experience with a traveling magician known as Mr. Electrico – who touched him on the nose and exclaimed “live forever!” – to which Bradbury took in the best way possible – his literature (which he began writing only days after this experience) will live forever. A couple short years later, the Bradbury family relocated to Los Angeles, where he was able to join the Los Angeles Science Fiction league as a teenager, and counted authors such as Robert Heinlein and Henry Kuttner among his mentors.

Bradbury was born on August 22nd, 1920, in rural Illinois. In 1932 at the age of twelve, Bradbury had a somewhat extraordinary experience with a traveling magician known as Mr. Electrico – who touched him on the nose and exclaimed “live forever!” – to which Bradbury took in the best way possible – his literature (which he began writing only days after this experience) will live forever. A couple short years later, the Bradbury family relocated to Los Angeles, where he was able to join the Los Angeles Science Fiction league as a teenager, and counted authors such as Robert Heinlein and Henry Kuttner among his mentors.

At the age of 19 his literary career began getting even more serious – and he honed with fantastical science fiction writing style by publishing his own fanzine, called Futuria Fantasia, and traveling to the first World Science Fiction convention, held in 1939 in New York City. His short stories began to be published in Science Fiction magazines such as Weird Tales and Super Science Stories. In the 1940s, Bradbury began to be published in high-end literary and social magazines like Harper’s, the American Mercury, Collier’s and The New Yorker – not typical for most science fiction writers. And to do it without losing sight of your style and genre – almost unheard of! Bradbury published short stories, series’, and novels over the coming years. In 1953 his novel Fahrenheit 451 hit the shelves – and is now regarded as one of his greatest works. It follows a futuristic world where censorship is in full force and follows the seduction of one firefighter through the world of literature. Fahrenheit 451 was closely followed by his collection The Golden Apples of the Sun, where the story inspiration for 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea was found. He followed up his works with more and more short stories, and more novels, until his later life, when he elected to turn more often towards poetry, drama and mysteries – including adapting his stories for the big screen. Despite being considered a primarily science fiction writer, Bradbury often considered his works more in the fantasy, horror and mystery genres – that he did not stay true to science fiction themes, with the exception of his novel Fahrenheit 451.

At the age of 19 his literary career began getting even more serious – and he honed with fantastical science fiction writing style by publishing his own fanzine, called Futuria Fantasia, and traveling to the first World Science Fiction convention, held in 1939 in New York City. His short stories began to be published in Science Fiction magazines such as Weird Tales and Super Science Stories. In the 1940s, Bradbury began to be published in high-end literary and social magazines like Harper’s, the American Mercury, Collier’s and The New Yorker – not typical for most science fiction writers. And to do it without losing sight of your style and genre – almost unheard of! Bradbury published short stories, series’, and novels over the coming years. In 1953 his novel Fahrenheit 451 hit the shelves – and is now regarded as one of his greatest works. It follows a futuristic world where censorship is in full force and follows the seduction of one firefighter through the world of literature. Fahrenheit 451 was closely followed by his collection The Golden Apples of the Sun, where the story inspiration for 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea was found. He followed up his works with more and more short stories, and more novels, until his later life, when he elected to turn more often towards poetry, drama and mysteries – including adapting his stories for the big screen. Despite being considered a primarily science fiction writer, Bradbury often considered his works more in the fantasy, horror and mystery genres – that he did not stay true to science fiction themes, with the exception of his novel Fahrenheit 451.

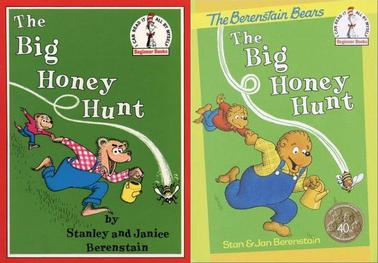

In 1941, Janice Grant and Stanley Berenstain met on their first day at the Philadelphia Museum School of Industrial Art and became close very quickly. At the onset of World War II, they took up different war effort posts (as a medical illustrator and riveter), but were eventually reunited and married in 1946. They found work as art teachers, then eventually became co-illustrators, publishing works like the Berenstain’s Baby Book in 1951 followed by many more (including, but not limited to Marital Blitz, How To Teach Your Children About Sex Without Making A Complete Fool of Yourself and Have A Baby, My Wife Just Had A Cigar). In the early 1960s the Berentain’s first “Berenstain Bears” book made it to a very important colleague and publisher – Theodore Geisel – or, as some of you may remember from our somewhat recent blog, Dr. Seuss!

In 1941, Janice Grant and Stanley Berenstain met on their first day at the Philadelphia Museum School of Industrial Art and became close very quickly. At the onset of World War II, they took up different war effort posts (as a medical illustrator and riveter), but were eventually reunited and married in 1946. They found work as art teachers, then eventually became co-illustrators, publishing works like the Berenstain’s Baby Book in 1951 followed by many more (including, but not limited to Marital Blitz, How To Teach Your Children About Sex Without Making A Complete Fool of Yourself and Have A Baby, My Wife Just Had A Cigar). In the early 1960s the Berentain’s first “Berenstain Bears” book made it to a very important colleague and publisher – Theodore Geisel – or, as some of you may remember from our somewhat recent blog, Dr. Seuss! Geisel traded ideas with the Berenstains for over a year – until he finally felt like they had a marketable product for the American public. In 1962, The Big Honey Hunt hit shelves across the USA. The Berenstains were working on their next book – featuring penguins – when Geisel got in touch to say another bear book was needed by demand, as The Big Honey Hunt was selling so undeniably well. Two years later The Bike Lesson came out… which began a waterfall of publications… at least one a year since then, but typically more than a few. A record 25 Berenstain Bears books were published in 1993 alone! Six titles have already been published in 2018. The immediate success of the Berenstain Bears lead to a situation not unlike the popular Hardy Boys series or Nancy Drew’s popularity – only for a younger age range and with a somewhat different tone. Not to mention all written and illustrated by the same authors, at least until Mike Berenstain took over the franchise in 2002. Jan and Stan were quite a busy pair for a number of years!

Geisel traded ideas with the Berenstains for over a year – until he finally felt like they had a marketable product for the American public. In 1962, The Big Honey Hunt hit shelves across the USA. The Berenstains were working on their next book – featuring penguins – when Geisel got in touch to say another bear book was needed by demand, as The Big Honey Hunt was selling so undeniably well. Two years later The Bike Lesson came out… which began a waterfall of publications… at least one a year since then, but typically more than a few. A record 25 Berenstain Bears books were published in 1993 alone! Six titles have already been published in 2018. The immediate success of the Berenstain Bears lead to a situation not unlike the popular Hardy Boys series or Nancy Drew’s popularity – only for a younger age range and with a somewhat different tone. Not to mention all written and illustrated by the same authors, at least until Mike Berenstain took over the franchise in 2002. Jan and Stan were quite a busy pair for a number of years!

As a stout Stuart supporter, Behn became attached to the royal court after King Charles II came back into power in 1660. Now we get into the exciting (and more traceable) details of this woman’s life – in 1666 her connections to the crown landed her a job as a spy during the Second Anglo-Dutch War and she arrived in the Netherlands in July of that year. However, her time there did not pan out as planned, as Charles II was extremely neglectful of payments – and Behn was forced to return to England after having to pawn some of her jewelry in order to live abroad. After her return to England, she began working as a playwright (though reportedly had written poetry prior to this job) for the King’s and Duke’s Companies in London. Her work as a scribe was popular, and her plays began to be seen on the stage in 1670

As a stout Stuart supporter, Behn became attached to the royal court after King Charles II came back into power in 1660. Now we get into the exciting (and more traceable) details of this woman’s life – in 1666 her connections to the crown landed her a job as a spy during the Second Anglo-Dutch War and she arrived in the Netherlands in July of that year. However, her time there did not pan out as planned, as Charles II was extremely neglectful of payments – and Behn was forced to return to England after having to pawn some of her jewelry in order to live abroad. After her return to England, she began working as a playwright (though reportedly had written poetry prior to this job) for the King’s and Duke’s Companies in London. Her work as a scribe was popular, and her plays began to be seen on the stage in 1670

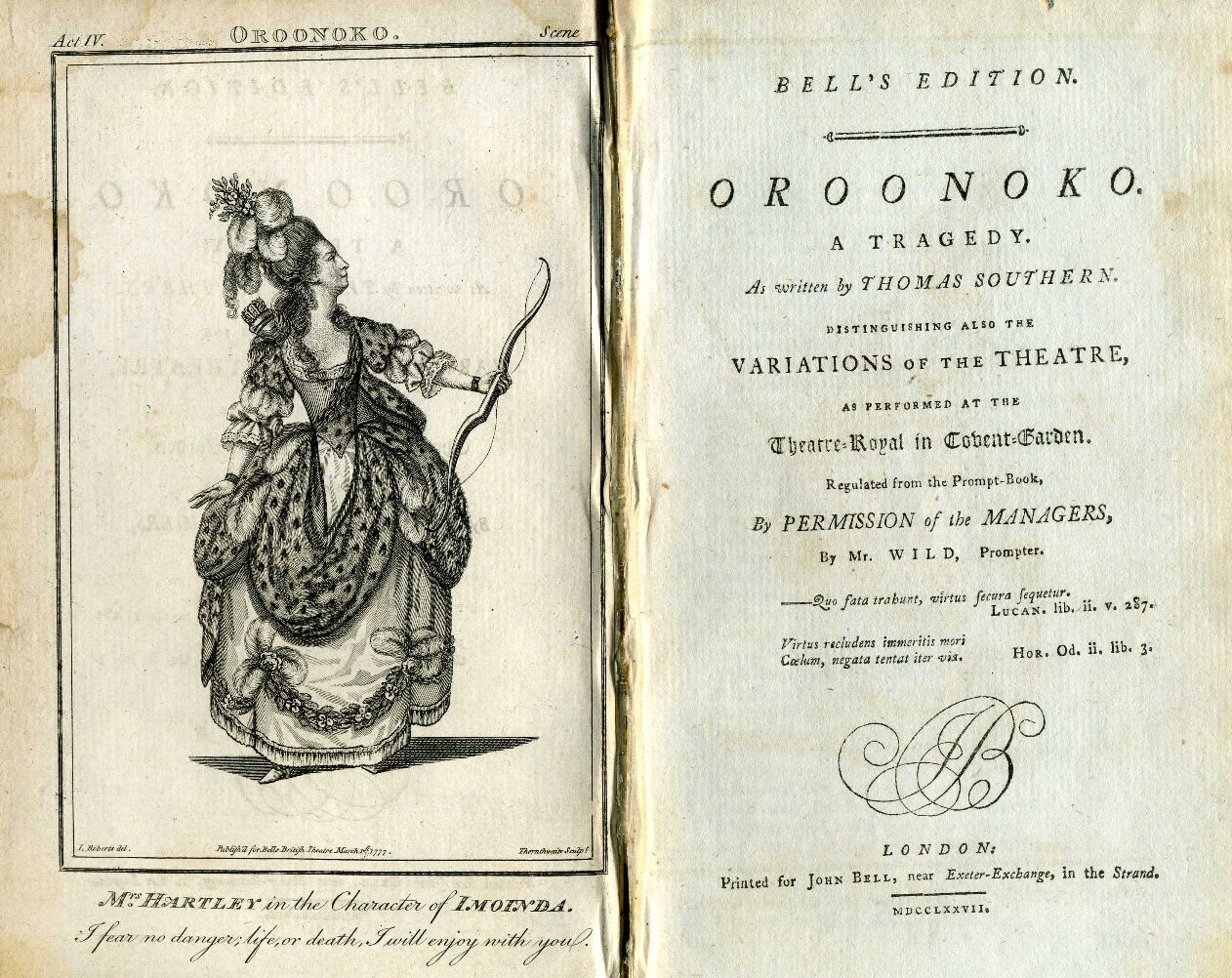

Publishing her famous novel Oroonoko just a year before her death in 1688, Behn truly wrote until her health completely deteriorated. Though she died at age 48 in relative poverty, Behn was buried in Westminster Abbey under her tombstone which reads, “Here lies a Proof that Wit can never be Defence enough against Mortality.” (Hilarious even in death…) Happy Birthday to this early feminist!

Publishing her famous novel Oroonoko just a year before her death in 1688, Behn truly wrote until her health completely deteriorated. Though she died at age 48 in relative poverty, Behn was buried in Westminster Abbey under her tombstone which reads, “Here lies a Proof that Wit can never be Defence enough against Mortality.” (Hilarious even in death…) Happy Birthday to this early feminist!

RBS provides you with the ultimate learning environment. The faculty is a who’s who of rare book experts, who unselfishly divulge their secrets, meant to be shared further with others. Students are free to select their favorite course(s) only, but once you experience this wonderful place, you will want to return soon and often. There is no competition, no cramming, no grades. This is learning at its best. Hint: get to know your peers; they will be delightful and VERY helpful to you. The RBS staff made hard work look easy; everything ran without a hitch. People enjoyed their chosen course, each a shortcut to expertise garnered over a lifetime. Casual, well-attended get-togethers formed naturally during breaks; people were very happy to be there. It felt like a week-long vacation from reality.

RBS provides you with the ultimate learning environment. The faculty is a who’s who of rare book experts, who unselfishly divulge their secrets, meant to be shared further with others. Students are free to select their favorite course(s) only, but once you experience this wonderful place, you will want to return soon and often. There is no competition, no cramming, no grades. This is learning at its best. Hint: get to know your peers; they will be delightful and VERY helpful to you. The RBS staff made hard work look easy; everything ran without a hitch. People enjoyed their chosen course, each a shortcut to expertise garnered over a lifetime. Casual, well-attended get-togethers formed naturally during breaks; people were very happy to be there. It felt like a week-long vacation from reality.

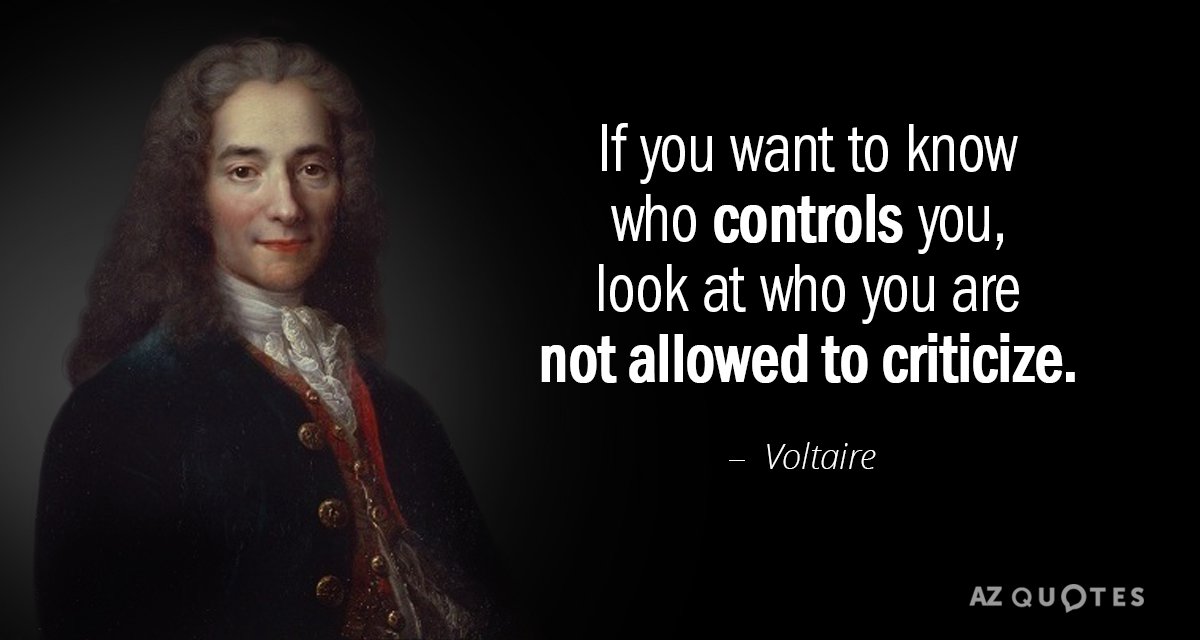

Now, Voltaire’s early life does not necessarily reflect my friends insistence that Voltaire “always got away with it.” As a matter of fact… he totally didn’t. Voltaire spent almost a year imprisoned in the Bastille for accusing a member of the royal family of incest with his daughter in a satirical poem (I mean… what exactly did he expect?). Seven months after his release in 1718, however, his play Oedipus debuted at the Comédie-Française in Paris a spectacular success. Not only did it land Voltaire on the literary map (for something other than scandal), but it also marked the first time he used his pen name – Voltaire, an anagram of the Latin spelling of his surname, AROVET LI (though there are several schools of thought for how Voltaire settled on “Voltaire”). Despite the importance of this name today, what is not necessarily commonly known is that throughout his lifetime Voltaire wrote under 178 different pen names.

Now, Voltaire’s early life does not necessarily reflect my friends insistence that Voltaire “always got away with it.” As a matter of fact… he totally didn’t. Voltaire spent almost a year imprisoned in the Bastille for accusing a member of the royal family of incest with his daughter in a satirical poem (I mean… what exactly did he expect?). Seven months after his release in 1718, however, his play Oedipus debuted at the Comédie-Française in Paris a spectacular success. Not only did it land Voltaire on the literary map (for something other than scandal), but it also marked the first time he used his pen name – Voltaire, an anagram of the Latin spelling of his surname, AROVET LI (though there are several schools of thought for how Voltaire settled on “Voltaire”). Despite the importance of this name today, what is not necessarily commonly known is that throughout his lifetime Voltaire wrote under 178 different pen names.