We recently saw an interesting article online, detailing the “Best Female Authors” of all time. On this, what would be Dr. Maya Angelou’s 90th birthday, we would like to channel her inner strength and power as a leading poet, singer, memoirist, and civil rights activist and honor some of the most famous female authors of all time.

Top Twenty-Five Female Authors of All Time in One Sentence or Less

Followed by the First Sentence or So Found about these Powerful Ladies on the Internet (A Rather Fascinating Social Experiment, No?)

(Obviously Debatable, but these names are based on Book Sales and those found to be Classics Today)

Jane Austen: “an English novelist known primarily for her six major novels, which interpret, critique and comment upon the British landed gentry at the end of the 18th century.”

Virginia Woolf: “an English writer, who is considered one of the foremost modernist authors of the 20th century and a pioneer in the use of stream of consciousness as a narrative device.”

Charlotte Bronte: “is one of the most famous Victorian women writers, only two of her poems are widely read today, and these are not her best or most interesting poems.”

Agatha Christie: “Lady Mallowan, DBE was an English writer. She is known for her 66 detective novels and 14 short story collections, particularly those revolving around her fictional detectives Hercule Poirot and Miss Marple.”

Mary Shelley: “an English novelist, short story writer, dramatist, essayist, biographer, and travel writer, best known for her Gothic novel Frankenstein: or, The Modern Prometheus (1818).”

Louisa May Alcott: “was born in Germantown, Pennsylvania on November 29, 1832. She and her sisters Anna, Elizabeth, and [Abba] May were educated by their father, teacher/philosopher A. Bronson Alcott, and raised on the practical Christianity of their mother, Abigail May.”

J.K. Rowling: “is the creator of the Harry Potter fantasy series, one of the most popular book and film franchises in history.”

George Eliot (Mary Anne Evans): “was an English novelist, poet, journalist, translator and one of the leading writers of the Victorian era.”

Emily Dickinson: “is one of America’s greatest and most original poets of all time.”

Sylvia Plath: “was one of the most dynamic and admired poets of the 20th century.”

Toni Morrison: “American writer noted for her examination of black experience (particularly black female experience) within the black community.”

Margaret Atwood: “is a Canadian poet, novelist, literary critic, essayist, inventor, and environmental activist.”

Elizabeth Gaskell: “often referred to as Mrs Gaskell, was an English novelist, biographer, and short story writer.”

Willa Cather: “established a reputation for giving breath to the landscape of her fiction.”

Dorothy Parker: “was an American poet, writer, critic, and satirist, best known for her wit, wisecracks and eye for 20th-century urban foibles.”

Gertrude Stein: “was an American author and poet best known for her modernist writings, extensive art collecting and literary salon in 1920s Paris.”

Ursula Le Guin: an “immensely popular author who brought literary depth and a tough-minded feminist sensibility to science fiction and fantasy with books like ‘The Left Hand of Darkness'”

Isabel Allende: “s a Chilean-American writer. Allende, whose works sometimes contain aspects of the genre of “magical realism,” is famous for novels such as The House of the Spirits (La casa de los espíritus, 1982) and City of the Beasts (La ciudad de las bestias, 2002), which have been commercially successful.”

Edna St. Vincent Millay: “received the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1923, the third woman to win the award for poetry, and was also known for her feminist activism.”

Mary Wollstonecraft: “an English writer and passionate advocate of educational and social equality for women.”

Alice Walker: “is a Pulitzer Prize-winning, African-American novelist and poet most famous for authoring ‘The Color Purple.'”

Maya Angelou: “an impactful civil rights leader who collaborated with Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X during the Civil Rights movement. “

Judy Blume: “spent her childhood in Elizabeth, NJ, making up stories inside her head. She has spent her adult years in many places, doing the same thing, only now she writes her stories down on paper.”

Betty Friedan: “a leading figure in the women’s movement in the United States, her 1963 book The Feminine Mystique is often credited with sparking the second wave of American feminism in the 20th century.”

Thank you to these powerful, courageous and wonderful writers for their influence on female empowerment!

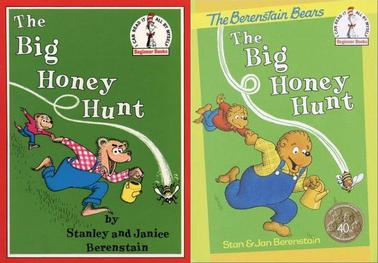

In 1941, Janice Grant and Stanley Berenstain met on their first day at the Philadelphia Museum School of Industrial Art and became close very quickly. At the onset of World War II, they took up different war effort posts (as a medical illustrator and riveter), but were eventually reunited and married in 1946. They found work as art teachers, then eventually became co-illustrators, publishing works like the Berenstain’s Baby Book in 1951 followed by many more (including, but not limited to Marital Blitz, How To Teach Your Children About Sex Without Making A Complete Fool of Yourself and Have A Baby, My Wife Just Had A Cigar). In the early 1960s the Berentain’s first “Berenstain Bears” book made it to a very important colleague and publisher – Theodore Geisel – or, as some of you may remember from our somewhat recent blog, Dr. Seuss!

In 1941, Janice Grant and Stanley Berenstain met on their first day at the Philadelphia Museum School of Industrial Art and became close very quickly. At the onset of World War II, they took up different war effort posts (as a medical illustrator and riveter), but were eventually reunited and married in 1946. They found work as art teachers, then eventually became co-illustrators, publishing works like the Berenstain’s Baby Book in 1951 followed by many more (including, but not limited to Marital Blitz, How To Teach Your Children About Sex Without Making A Complete Fool of Yourself and Have A Baby, My Wife Just Had A Cigar). In the early 1960s the Berentain’s first “Berenstain Bears” book made it to a very important colleague and publisher – Theodore Geisel – or, as some of you may remember from our somewhat recent blog, Dr. Seuss! Geisel traded ideas with the Berenstains for over a year – until he finally felt like they had a marketable product for the American public. In 1962, The Big Honey Hunt hit shelves across the USA. The Berenstains were working on their next book – featuring penguins – when Geisel got in touch to say another bear book was needed by demand, as The Big Honey Hunt was selling so undeniably well. Two years later The Bike Lesson came out… which began a waterfall of publications… at least one a year since then, but typically more than a few. A record 25 Berenstain Bears books were published in 1993 alone! Six titles have already been published in 2018. The immediate success of the Berenstain Bears lead to a situation not unlike the popular Hardy Boys series or Nancy Drew’s popularity – only for a younger age range and with a somewhat different tone. Not to mention all written and illustrated by the same authors, at least until Mike Berenstain took over the franchise in 2002. Jan and Stan were quite a busy pair for a number of years!

Geisel traded ideas with the Berenstains for over a year – until he finally felt like they had a marketable product for the American public. In 1962, The Big Honey Hunt hit shelves across the USA. The Berenstains were working on their next book – featuring penguins – when Geisel got in touch to say another bear book was needed by demand, as The Big Honey Hunt was selling so undeniably well. Two years later The Bike Lesson came out… which began a waterfall of publications… at least one a year since then, but typically more than a few. A record 25 Berenstain Bears books were published in 1993 alone! Six titles have already been published in 2018. The immediate success of the Berenstain Bears lead to a situation not unlike the popular Hardy Boys series or Nancy Drew’s popularity – only for a younger age range and with a somewhat different tone. Not to mention all written and illustrated by the same authors, at least until Mike Berenstain took over the franchise in 2002. Jan and Stan were quite a busy pair for a number of years!

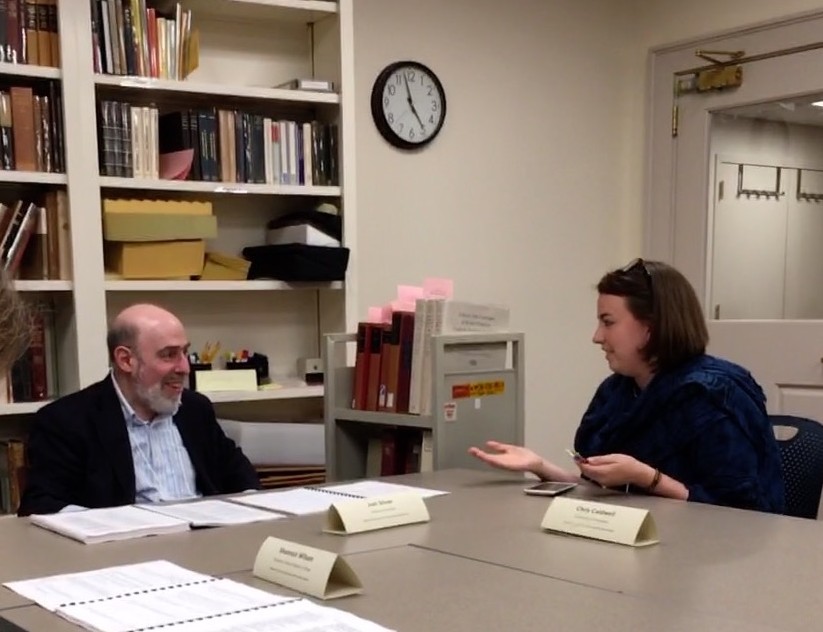

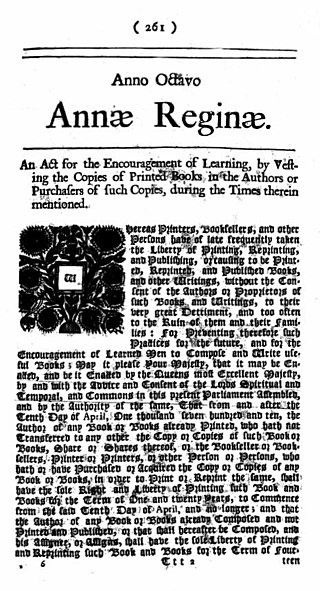

RBS provides you with the ultimate learning environment. The faculty is a who’s who of rare book experts, who unselfishly divulge their secrets, meant to be shared further with others. Students are free to select their favorite course(s) only, but once you experience this wonderful place, you will want to return soon and often. There is no competition, no cramming, no grades. This is learning at its best. Hint: get to know your peers; they will be delightful and VERY helpful to you. The RBS staff made hard work look easy; everything ran without a hitch. People enjoyed their chosen course, each a shortcut to expertise garnered over a lifetime. Casual, well-attended get-togethers formed naturally during breaks; people were very happy to be there. It felt like a week-long vacation from reality.

RBS provides you with the ultimate learning environment. The faculty is a who’s who of rare book experts, who unselfishly divulge their secrets, meant to be shared further with others. Students are free to select their favorite course(s) only, but once you experience this wonderful place, you will want to return soon and often. There is no competition, no cramming, no grades. This is learning at its best. Hint: get to know your peers; they will be delightful and VERY helpful to you. The RBS staff made hard work look easy; everything ran without a hitch. People enjoyed their chosen course, each a shortcut to expertise garnered over a lifetime. Casual, well-attended get-togethers formed naturally during breaks; people were very happy to be there. It felt like a week-long vacation from reality.

Now, Voltaire’s early life does not necessarily reflect my friends insistence that Voltaire “always got away with it.” As a matter of fact… he totally didn’t. Voltaire spent almost a year imprisoned in the Bastille for accusing a member of the royal family of incest with his daughter in a satirical poem (I mean… what exactly did he expect?). Seven months after his release in 1718, however, his play Oedipus debuted at the Comédie-Française in Paris a spectacular success. Not only did it land Voltaire on the literary map (for something other than scandal), but it also marked the first time he used his pen name – Voltaire, an anagram of the Latin spelling of his surname, AROVET LI (though there are several schools of thought for how Voltaire settled on “Voltaire”). Despite the importance of this name today, what is not necessarily commonly known is that throughout his lifetime Voltaire wrote under 178 different pen names.

Now, Voltaire’s early life does not necessarily reflect my friends insistence that Voltaire “always got away with it.” As a matter of fact… he totally didn’t. Voltaire spent almost a year imprisoned in the Bastille for accusing a member of the royal family of incest with his daughter in a satirical poem (I mean… what exactly did he expect?). Seven months after his release in 1718, however, his play Oedipus debuted at the Comédie-Française in Paris a spectacular success. Not only did it land Voltaire on the literary map (for something other than scandal), but it also marked the first time he used his pen name – Voltaire, an anagram of the Latin spelling of his surname, AROVET LI (though there are several schools of thought for how Voltaire settled on “Voltaire”). Despite the importance of this name today, what is not necessarily commonly known is that throughout his lifetime Voltaire wrote under 178 different pen names.

Barrie wrote several successful plays (and a couple flukes), but his third script brought him into contact with a young actress of the day – Mary Ansell – who would later, in 1894, become Barrie’s wife. For their union Barrie gifted Mary a St. Bernard puppy – who would become the inspiration for “Nana” in later years. They settled in London but kept a country home in Farnham, Surrey. In 1897 Barrie became acquainted with a nearby family – the Llewelyn Davies family.

Barrie wrote several successful plays (and a couple flukes), but his third script brought him into contact with a young actress of the day – Mary Ansell – who would later, in 1894, become Barrie’s wife. For their union Barrie gifted Mary a St. Bernard puppy – who would become the inspiration for “Nana” in later years. They settled in London but kept a country home in Farnham, Surrey. In 1897 Barrie became acquainted with a nearby family – the Llewelyn Davies family. Inspired largely by the stories he told to the Llewelyn Davies family, Barrie began to formulate a story of a boy who wouldn’t grow up, who flew around and had adventures. Not unlike Charles Dodgson’s Alice a century before, Barrie began to write his story into a play and once debuted in 1904, the play Peter Pan; or the Boy Who Wouldn’t Grow Up was an immediate success. George Bernard Shaw said of the performance, “ostensibly a holiday entertainment for children, but really a play for grown-up people” – a wonderful description of the meanings and metaphors found in Peter Pan. Though children may see the adventure story on the outside, the adults in the audience could see what was really at play (pun intended) – Barrie’s social commentary on the adult’s fear of time and growing old and losing their childish innocence and fun, to name just a few.

Inspired largely by the stories he told to the Llewelyn Davies family, Barrie began to formulate a story of a boy who wouldn’t grow up, who flew around and had adventures. Not unlike Charles Dodgson’s Alice a century before, Barrie began to write his story into a play and once debuted in 1904, the play Peter Pan; or the Boy Who Wouldn’t Grow Up was an immediate success. George Bernard Shaw said of the performance, “ostensibly a holiday entertainment for children, but really a play for grown-up people” – a wonderful description of the meanings and metaphors found in Peter Pan. Though children may see the adventure story on the outside, the adults in the audience could see what was really at play (pun intended) – Barrie’s social commentary on the adult’s fear of time and growing old and losing their childish innocence and fun, to name just a few.

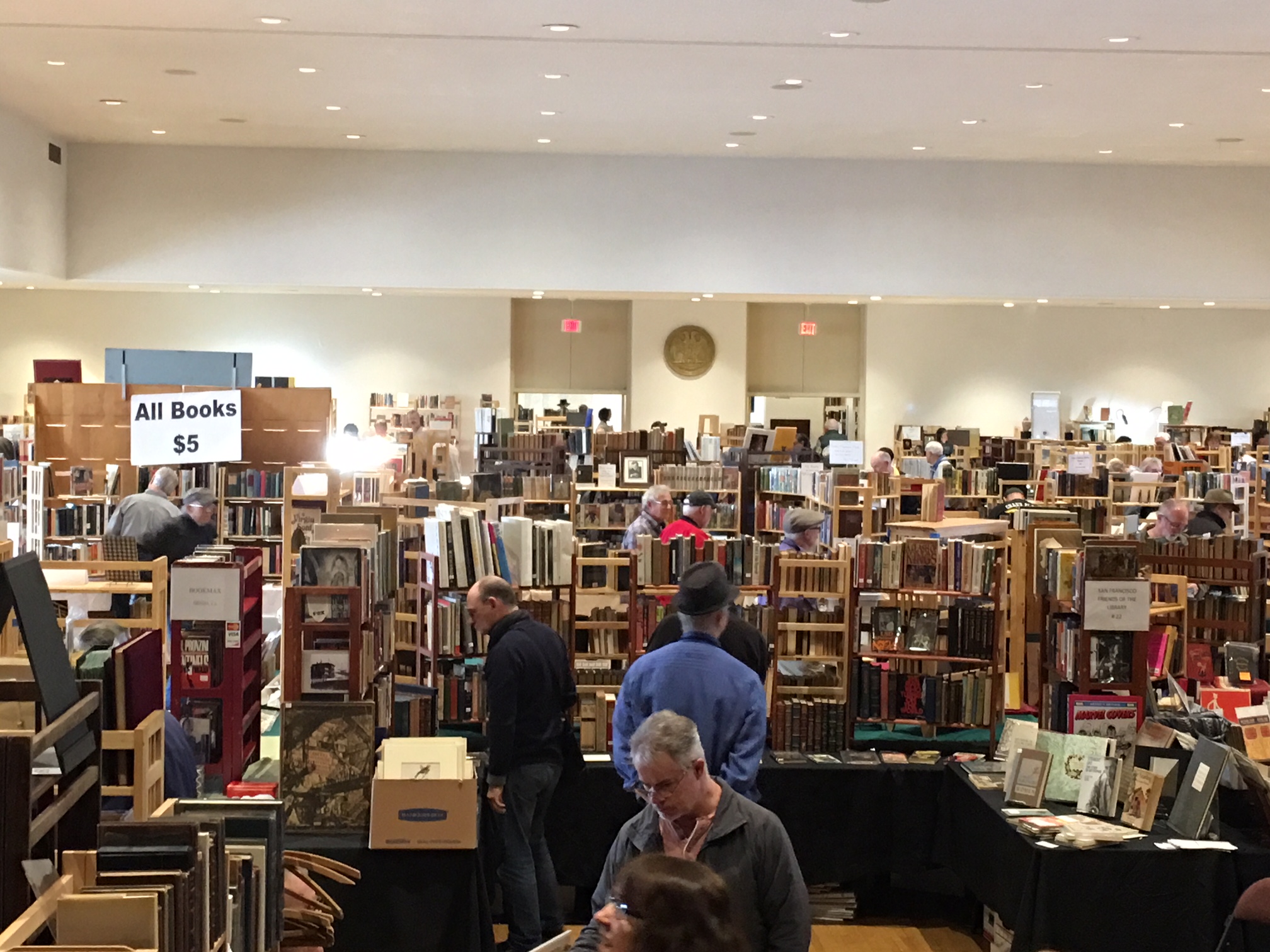

This particular fair was also memorable for another reason… it was the first ever for my new assistant, Samm Fricke. Samm came on board last Wednesday. Yes, you read that right, she’d only been in my employ for 2 days before I whisked her off to help me man the Tavistock Books’ booth. She did great! And the good ship Tavistock…? The buying was great*; sales, not so much. But that said, unless someone buys out your booth, there’s always room for improvement, isn’t there?

This particular fair was also memorable for another reason… it was the first ever for my new assistant, Samm Fricke. Samm came on board last Wednesday. Yes, you read that right, she’d only been in my employ for 2 days before I whisked her off to help me man the Tavistock Books’ booth. She did great! And the good ship Tavistock…? The buying was great*; sales, not so much. But that said, unless someone buys out your booth, there’s always room for improvement, isn’t there?

* watch for our New Acquisitions list… lots of interesting material will be coming your way!

* watch for our New Acquisitions list… lots of interesting material will be coming your way!