***

It’s been a while since we checked in with a more personal blog, so we thought that with the end of summer in sight we’d see what our Master and Commander Vic Zoschak has been up to these last couple of years!

***

Q: So V, here we are in 2022 – how have you been this past year, how has life been in general?

We’re into our 4th year of Covid Ms P, and I guess you could say I’ve adapted to that reality. Last summer, I completely closed the shop to the public, and have been ‘on-line’ only ever since, and to be honest, that’s worked out ok.

*

Q: How has “regular life” played a part in your business over the past many months? The last time we checked in was at the heart of the pandemic. Have you noticed any notable changes since?

I avoided Covid for the first 3 years, but here, early in the 4th, I did catch it a couple weeks back… a variant, I think, for I’m fully vaxxed & boosted. Let’s just say it was not a fun couple of days. But that aside, in response to the on-going pandemic, last summer, I changed my work routine, adopting a semi-retired approach to my work life, only going into the shop 4-5 hours a day, freeing up some personal time to spend with the dogs, catch a few more Giants games, read a few more books… I must say, I find this newer, more relaxed lifestyle quite enjoyable!

*

Q: You recently celebrated 25 years on Webster Street in sunny Alameda, California. How have you seen Alameda and your location change over the past two and a half decades, as one of the longest running and most-established businesses on the island?

Time does fly, does it not!?! Seems like just yesterday I opened the door at 1503 Webster, but that was actually July 15, 1997. When I opened the shop, the west end of Alameda had just experienced a devastating blow to the local businesses… by that I mean the Navy had closed NAS Alameda in April of that year. All of a sudden a large consumer base was gone. As a result, lots of vacant store fronts existed on Webster, so a new business opening on Webster was a big event, in this case, the Mayor, the Vice-Mayor & the head of the Alameda Chamber of Commerce all came for my ‘ribbon-cutting’. The West end was a long time in coming back, but now, 25 years later, Webster is the main mercantile street in Alameda’s west end. It’s quite vibrant actually, with lots of restaurants & other interesting businesses. But that said, despite the current vibrancy, the street did not, and will not, support a specialized antiquarian book store like mine… were it not for my on-line / mail-order sales component, I would have had to close the doors long ago.

*

Q: Now that the book world is back to hosting in-person book fairs, how have you seen the changes brought about by the past couple of years influence the book world of today? Which changes are for the better? And on that note, do you find any for the worse?

This one is difficult for me to answer, for as part of my semi-retired approach to business, I’ve decided to omit book fairs from my current business paradigm [except for the local, one-day Sacramento show]. I find it exhausting to be a one-man exhibitor, gone for 5-6 days…. pack the books, drive to the event, set up the booth, man it [solo] for 3-4 days, pack out, drive back to Alameda, unpack all the boxes & reshelve the books. Too much work for this 70 year old… an example of the old leisure vs income dichotomy, with me falling down on the leisure side of the equation.

*

Q: What would you say your bookselling high and low were, in recent months? This could be an event or a meeting of sorts, or perhaps a notable sale?

I think most booksellers will agree that their favorite book is the one that just sold. But to answer your specific question, two recent sales do come to mind… I helped one of my customers find & acquire a very nice copy of Dickens’ Christmas Carol, and one of my institutional customers ordered an 1866 broadside published out of San Francisco, Freedom’s Footsteps. This latter quite rare, with only a couple copies known to exist.

*

Q: What do you have on the horizon of interest for yourself and/or for Tavistock Books?

Well, the ILAB Congress is next month, being held in Oxford, England. I’ll be attending, and we’re concluding the trip with some time in London, and then Paris. So that definitely that trip is of interest!

*

Q: For a fun last question – what is your favorite item to come across your desk in the last few months? Let’s see it!

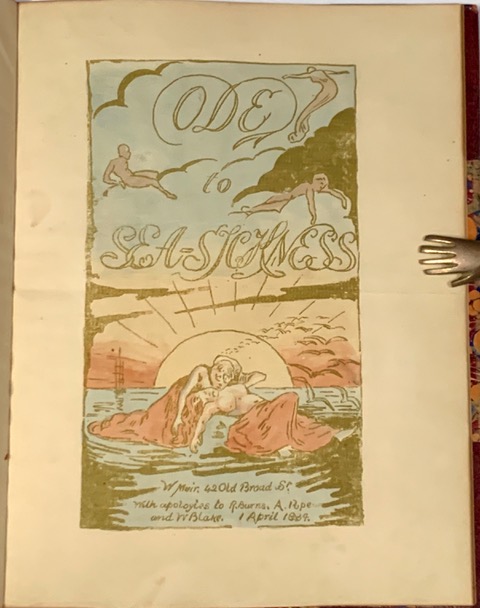

Oh my, that’s a challenge to name just one! Well, let’s see… as you know, like many of the local booksellers, I tend to scout the monthly Alameda Point Flea Market. Not too long ago, I purchased a book that mimics the great William Blake, Ode to Sea-Sickness, by William Muir. Quite scarce. I think it’s pretty cool, and it will be offered in my stand at the next Biblio Live VBF. Here’s an image of the title page.

Vic’s Ode to Sea-sickness!

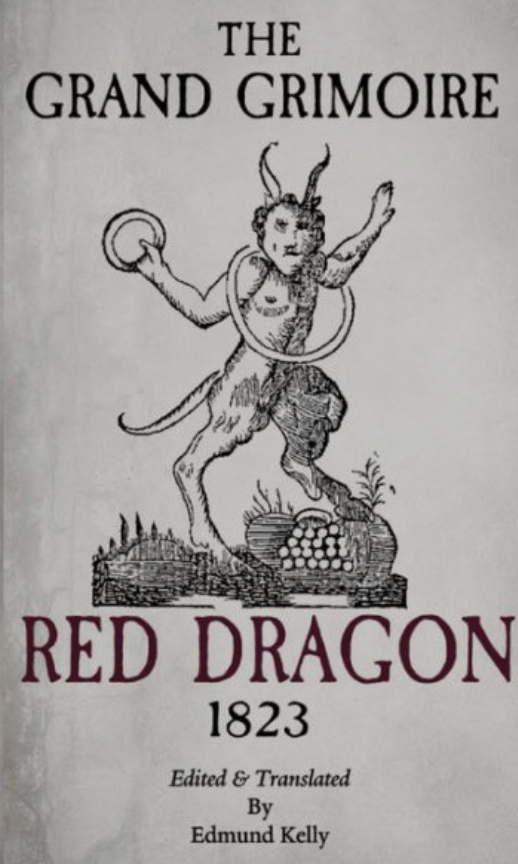

Several grimoires make their way onto the scene in the 1500s, with a steady stream of them from thereon after. Some of these include Les Secrets merveilleux de la magic naturelle du petit Albert (1272), the Grand Grimoire (1521), Le Dragon Rouge (published in 1822 but supposedly dating back to 1522), and the Grimoire of Armadel (written in the 1600s, not published until 1980). As time passes and the ability to write becomes more commonplace, availability of paper and writing utensils increase, more and more grimoires emerge. Notable antiquarian collections of grimoires can be found at the Cornell University Library, the Ritman Library in the Netherlands, and the Museum of Witchcraft and Magic in the UK.

Several grimoires make their way onto the scene in the 1500s, with a steady stream of them from thereon after. Some of these include Les Secrets merveilleux de la magic naturelle du petit Albert (1272), the Grand Grimoire (1521), Le Dragon Rouge (published in 1822 but supposedly dating back to 1522), and the Grimoire of Armadel (written in the 1600s, not published until 1980). As time passes and the ability to write becomes more commonplace, availability of paper and writing utensils increase, more and more grimoires emerge. Notable antiquarian collections of grimoires can be found at the Cornell University Library, the Ritman Library in the Netherlands, and the Museum of Witchcraft and Magic in the UK.

As time went on and interest in her intelligence, loveliness, refinement and gentility grew, Juliette became friendly with all manner of people. Some of the most notorious members of her salon were François-René de Chateaubriand (a French politician, diplomat, activist, historian and writer who ended up as one of Juliette’s life-long friends), Benjamin Constant (Swiss-French political activist and writer), Prince Augustus of Prussia (whose proposal she would ultimately reject), and the political Madame Germaine de Staël. Juliette enjoyed almost unprecedented independence in her ability to entertain and act as she saw fit – she also received many proposals, and was “courted” by many men, but never, as far as history is concerned, betrayed her husband. People were attracted to Juliette not solely because of her good looks, but because of her academic and literary prowess, her interest in social and political endeavors, and her apparent ability to charm a room with a single glance, smile or comment. Juliette Récamier was the epitome of an esteemed lady – a patron, a scholar, a magnetic and irresistible personality, and a beautiful and charismatic individual. Political and intellectual persons flocked to her sitting room, and the discourses had there (both with Madame Récamier and with each other) can be credited with several of the ideas and large-scale changes in the turbulence of the French politics of the day.

As time went on and interest in her intelligence, loveliness, refinement and gentility grew, Juliette became friendly with all manner of people. Some of the most notorious members of her salon were François-René de Chateaubriand (a French politician, diplomat, activist, historian and writer who ended up as one of Juliette’s life-long friends), Benjamin Constant (Swiss-French political activist and writer), Prince Augustus of Prussia (whose proposal she would ultimately reject), and the political Madame Germaine de Staël. Juliette enjoyed almost unprecedented independence in her ability to entertain and act as she saw fit – she also received many proposals, and was “courted” by many men, but never, as far as history is concerned, betrayed her husband. People were attracted to Juliette not solely because of her good looks, but because of her academic and literary prowess, her interest in social and political endeavors, and her apparent ability to charm a room with a single glance, smile or comment. Juliette Récamier was the epitome of an esteemed lady – a patron, a scholar, a magnetic and irresistible personality, and a beautiful and charismatic individual. Political and intellectual persons flocked to her sitting room, and the discourses had there (both with Madame Récamier and with each other) can be credited with several of the ideas and large-scale changes in the turbulence of the French politics of the day.

During her time in France, Mary witnessed the execution of King Louis XIV, even saw some of her friends executed when the Jacobins took power, was refused her requests to leave the country, and lived with American adventurer Gilbert Imlay, with whom she had a passionate affair. (“Which of these things is not like the other?”, you may as well ask!) Though all of her experiences greatly influenced her thoughts and views of humanity, she decided to put her individuality and power to the test by living unmarried with a man, and bearing a child by him, named Fanny after her dearest deceased friend. Wollstonecraft and Imlay remained together long enough to do a bit of traveling, and for Mary to publish two other works – An Historical and Moral View of the Origin and Progress of the French Revolution, and a introspective and personal travelogue, Letters Written During a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway and Denmark. After Imlay left her, Wollstonecraft returned to England to pursue him, and after bouts of suicidal tendencies and depression fell back into Joseph Johnson’s literary circle. Eventually, Mary began striking up a friendship, and then a passionate love affair with William Godwin. Of her work (her travel Letters, in particular) Godwin wrote, “If ever there was a book calculated to make a man in love with its author, this appears to me to be the book. She speaks of her sorrows, in a way that fills us with melancholy, and dissolves us in tenderness, at the same time that she displays a genius which commands all our admiration.” Despite not being proponents of marriage in general, the two wed shortly before Wollstonecraft’s second child was born – her daughter Mary, who would later go on to write Frankenstein as Mary Shelley (to read our blog on the second brilliant female mind in the family, click

During her time in France, Mary witnessed the execution of King Louis XIV, even saw some of her friends executed when the Jacobins took power, was refused her requests to leave the country, and lived with American adventurer Gilbert Imlay, with whom she had a passionate affair. (“Which of these things is not like the other?”, you may as well ask!) Though all of her experiences greatly influenced her thoughts and views of humanity, she decided to put her individuality and power to the test by living unmarried with a man, and bearing a child by him, named Fanny after her dearest deceased friend. Wollstonecraft and Imlay remained together long enough to do a bit of traveling, and for Mary to publish two other works – An Historical and Moral View of the Origin and Progress of the French Revolution, and a introspective and personal travelogue, Letters Written During a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway and Denmark. After Imlay left her, Wollstonecraft returned to England to pursue him, and after bouts of suicidal tendencies and depression fell back into Joseph Johnson’s literary circle. Eventually, Mary began striking up a friendship, and then a passionate love affair with William Godwin. Of her work (her travel Letters, in particular) Godwin wrote, “If ever there was a book calculated to make a man in love with its author, this appears to me to be the book. She speaks of her sorrows, in a way that fills us with melancholy, and dissolves us in tenderness, at the same time that she displays a genius which commands all our admiration.” Despite not being proponents of marriage in general, the two wed shortly before Wollstonecraft’s second child was born – her daughter Mary, who would later go on to write Frankenstein as Mary Shelley (to read our blog on the second brilliant female mind in the family, click