After John Barnard Davis passed away on May 19, 1881, his obituary appeared in the British Medical Journal. Davis was lauded as a “venerable practitioner and eminent anthropologist.” But today, what most people remember about Davis is his extensive collection of human skulls.

An Incredible Collection of Crania

By 1867, Davis had amassed a collection of 1,474 skulls from various parts of the world. Truly, Davis’ collecting of skulls was quite obsessive (though we suspect many a collector of antiquarian books can empathize with his mania). Davis used his political connections and wealth to obtain skulls that were highly coveted in Britain. For example, he managed to amass a great number of skulls from Tanzania, which were quite difficult to procure. And though Davis had never been to New Zealand himself, he invested heavily there and used his financial sway to get more specimens.

Why such an obsession with crania? Davis firmly believed that one could glean extensive racial information, including the degree of an individual’s racial hybridity, from the measurements of the individual’s skull. Davis wrote extensively on the topic, and his works were soon used as central texts for craniologists and racial scholars. Davis primarily focused on comparing “aboriginal” skulls from Britain with “aboriginal” skulls in other parts of the world.

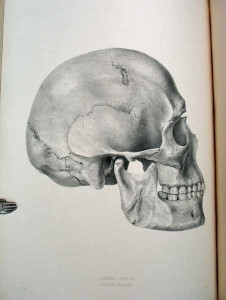

In 1865, Davis produced his magnum opus with fellow physician John Thurnam. Crania Britannica is an absolutely exhaustive work, including over 60 plates. The work would later receive a rather glowing recommendation in Anthropological Review (Vol 6, No 20, 1868): “Never before, certainly, had representations of skulls been produced that would vie, in beauty and accuracy, with the sixty that form the text on which the authors so lovingly and learnedly discourse.” The reviewer also noted that Davis and Thurnam had a few significant differences of opinion, and that Davis clung too tightly to the accidental variations among skulls.

The Evolution of Craniometry

Yet Davis was hardly an outlier in the scientific community; the nineteenth century saw a veritable explosion of interest in human measurement, and especially in craniometry. In 1812, the Edinburgh Encyclopedia defined craniometry as “the art of measuring the skulls of animals so as to discover their specific differences.” The concept itself was not altogether new; doctors and scientists had long paid attention to variations in physical form. Hippocrates, considered a pioneer in physical anthropology, made multitudinous descriptions of different skulls, though he never actually measured them.

That began in the fifteenth century. Leonardo da Vinci is probably one of the earliest people of note to apply a theory of skull measurement; he used a number of lines related to specific structures in the head to study the human form more closely. Albrecht Durer’s 1528 treatise on cranial measurements represented the first published attempt to apply anthropometry to aesthetics. Adrian van der Spigel made the first truly scientific attempt at measuring the cranium, defining four lines: the frontal, sinciptal, facial, and occipital. Spigel also argued that the lines of well-proportioned skulls would all be the same length.

Then in 1699, a Cambridge doctor took measurements of a chimpanzee skull. His data prompted Edward Tyson to suggest that there was an intermediate animal between humans and monkeys. Tyson called this animal a “pygmy.” Unfortunately for Tyson, his “pygmy” skull later turned out to be…another chimpanzee skull. Nevertheless, the idea of an intermediate animal persisted. From that time on, the practice of craniometry blossomed. Countless systems of skull analysis emerged, each with its own idiosyncrasies.

As the eighteenth century unfolded, practitioners of craniometry became increasingly interested in correlations between various physical measurements and intelligence. It was quite common to use these measurements to “demonstrate” that people of their own race were intellectually superior to others. Pieter Camper introduced the concept of “facial angle” in his Dissertation sur les varietes naturelles de la physionomie, published posthumously in 1791. He noted that the ideal facial angle was the same as that used by famous Greek sculptors. Though Camper’s survey was limited to a very small number of skulls, his idea fascinated physicians and scientists. They applied it to skulls from people of both European and African descent, attributing the differences in facial angle to natural superiority of Europeans.

Craniometry to Justify Racism

Camper’s chief opponent, Johann Friedrich Blumenbach, rejected the theory of lines and angles. He argued for much closer examination of the skull, particularly the maxillary and frontal bones. In 1795, Blumenbach also suggested a standardized method of positioning the skull so that measurements could be standardized and reproduced. But it was Paul Broca who would institute an accurate, precise technique for measuring skulls. His goal was to obtain sufficient data to be able to authoritatively determine the race of a skull’s owner by its measurements, thereby creating a set of racial “types” for skulls.

Meanwhile, there was a marked shift from using skulls to determine only racial identity, to using skulls to determine supposedly innate differences between the moral and mental capacities of various races. In addition to skull measurements, scientists also relied on a given race’s technological advancements and ability to master Western tools as further gauges of intellect. This paradigm began to shift a bit in the early nineteenth century; whereas the eighteenth-century view of race was more fixed in terms of racial attributes and divisions; the new century viewed race as more fluid.

This was especially true as theories of evolution emerged. Yet the skull remained a central focus, and researchers continued to seek ways to quantify intellectual capacity. The actual capacity of the skull even became a focus; Samuel Morton first filled skulls with white peppers, and later with lead gunshot, to measure how much it would hold. Friedrich Tiedemann used millet seed. Camper’s angle came under fire as anatomists like Anders Retzius and George Combe proposed closer examination of the proportions of different parts of the brain and skull.

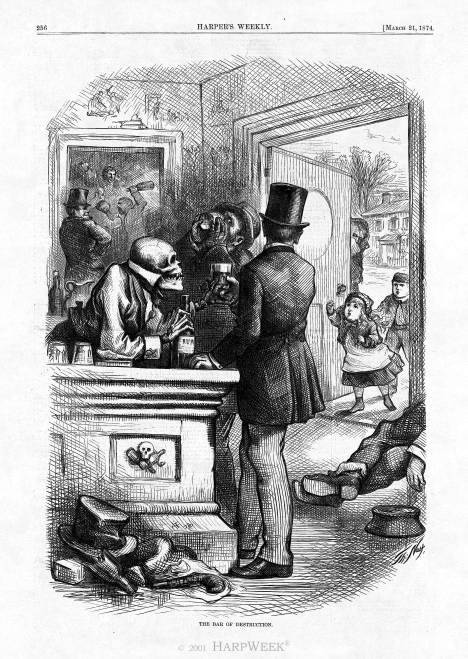

George Combe’s Theory of Phrenology would prove incredibly influential—and pernicious. Though the practice of phrenology was often mocked, it also heavily influenced any number of policies and institutions during the nineteenth century, from education to criminal reform. Leading thinkers like GWF Hegel and Thomas Edison were attracted to the pseudoscience, as were illustrious authors like George Eliot, Honore de Balzac, and the Bronte sisters. Even Queen Victoria dabbled in phrenology.

By the time Davis and Thurnam published Crania Britannica in 1865, phrenology had already fallen out of scholarly favor, though it remained in the public’s consciousness as a popular fad. Craniometry remained a strong interest in the medical and scientific community, not least because it reinforced racist ideology. However, toward the end of the 1800’s, even these theories wore thin. Today, craniometry still has some applications, though it’s practiced much differently than it was in Davis’ day. While Davis’ theories have been discarded, his incredible skull collection survives relatively intact, and his Crania Britannica offers an incredible window into the attitudes, knowledge, and methodology of his time.

Related Books and Ephemera

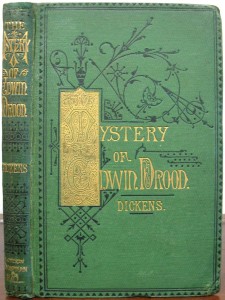

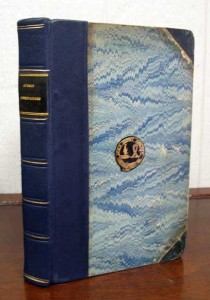

Crania Britannica

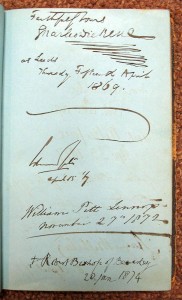

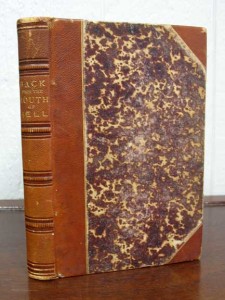

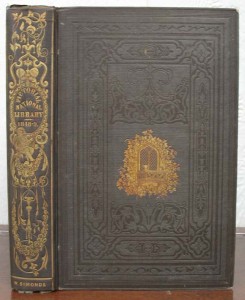

Davis and Thurnam’s work bears the drop title “Delineations and Descriptions of the Skulls of the Aboriginal and Early Inhabitants of the British Islands: with Notices of Their Other Remains.” Volume I contains the text, while Volume II includes plates and descriptions. It’s bound with “Osteological Contributions to the Natural History of the Chimpanzees (Troglodytes) and Orangs (Pithecus). No. IV. Description of the Cranium of an Adult Male Gorilla from the River Danger, West Coast of Africa, … ” by Professor Owen (1851). This work was published for subscribers and contains 67 lithographic plates, while this particular copy includes five additional plates illustrating the Owen article. It bears unobtrusive ex-lib markings. Though the joints are rubbed, this is overall a solid Very Good copy. Details>>

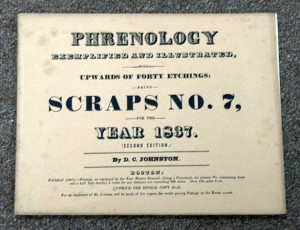

Phrenology Exemplified and Illustrated, with Upwards of Forty Etchings

David Claypoole Johnson was known as “the American Hogarth,” and this work, in Scraps No 7 (1837) offers a satirical look, both textually and graphically, at the “science”of phrenology.” By this time, phrenology had fallen out of favor–though it would eventually reemerge as a sort of parlor entertainment in the 1860’s and 1870’s. This is the second edition, which doesn’t appear in American Imprints. It’s bound in buff paper wrappers. With light extremity wear and minor foxing, it’s withal a Very Good+ copy. Details>>

David Claypoole Johnson was known as “the American Hogarth,” and this work, in Scraps No 7 (1837) offers a satirical look, both textually and graphically, at the “science”of phrenology.” By this time, phrenology had fallen out of favor–though it would eventually reemerge as a sort of parlor entertainment in the 1860’s and 1870’s. This is the second edition, which doesn’t appear in American Imprints. It’s bound in buff paper wrappers. With light extremity wear and minor foxing, it’s withal a Very Good+ copy. Details>>

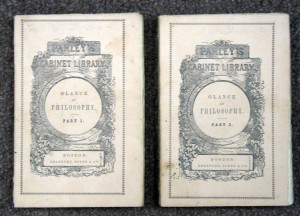

A Glance at Philosophy, Mental, Moral, and Social

American author Samuel Griswold Goodrich was better known by his pseudonym, Peter Parley. His Peter Parley Cabinet Library was quite popular at the time, and this title, published in 1845, was #14 in the series. The first part begins with a discussion of phrenology. It’s uncommon to find this title as presented here, in the original pink printed wrappers with a series advertisement on the rear wrapper. Overall, this is a Very Good set. Details>>

American author Samuel Griswold Goodrich was better known by his pseudonym, Peter Parley. His Peter Parley Cabinet Library was quite popular at the time, and this title, published in 1845, was #14 in the series. The first part begins with a discussion of phrenology. It’s uncommon to find this title as presented here, in the original pink printed wrappers with a series advertisement on the rear wrapper. Overall, this is a Very Good set. Details>>

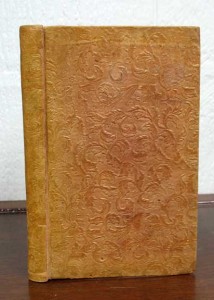

Phrenology Known by Its Fruits Being a Brief Overview of Doctor’s Brigham’s Late Work, Entitled “Observations on the Influence of Religion Upon the Health and Physical Welfare of Mankind”

Psychiatrist Amariah Brigham was one of the founding members of the professional organization that was the precursor to the American Psychiatric Association and served as the first director o the Utica Psyciatric Center. Brigham and others in the psychiatric community used phrenology to justify exempting the mentally ill from criminal punishment, and he ardently campaigned to excuse William Freeman from the gallows after he was convicted of murdering John G Van Nest. Prior to that incident, however, David Meredith Reese published Phrenology Known by its Fruits, an exploration of Brigham’s philosophy. Reese, himself a physician, served as physician-in-chief at Bellevue Hospital and published a number of works. Square and tight, this volume was professionally rebacked, with about 90% of the original spine cloth laid-down. It displays the usual bit of foxing but is overall a Very Good to Very Good+ copy. Details>>

Psychiatrist Amariah Brigham was one of the founding members of the professional organization that was the precursor to the American Psychiatric Association and served as the first director o the Utica Psyciatric Center. Brigham and others in the psychiatric community used phrenology to justify exempting the mentally ill from criminal punishment, and he ardently campaigned to excuse William Freeman from the gallows after he was convicted of murdering John G Van Nest. Prior to that incident, however, David Meredith Reese published Phrenology Known by its Fruits, an exploration of Brigham’s philosophy. Reese, himself a physician, served as physician-in-chief at Bellevue Hospital and published a number of works. Square and tight, this volume was professionally rebacked, with about 90% of the original spine cloth laid-down. It displays the usual bit of foxing but is overall a Very Good to Very Good+ copy. Details>>

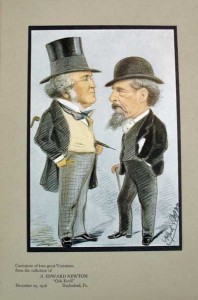

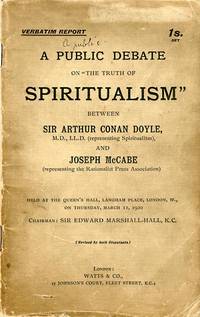

While Conan Doyle was respected in Spiritualist circles, his blind devotion led him headlong into ridicule on more than one occasion. He was taken in by Frances Griffith and Elsie Wright’s forged photographs of fairies. Conan Doyle, accepting the photographs as authentic, wrote a few pamphlets and The Coming of Fairies (1922), which made him a bit of a laughingstock. Later, Conan Doyle invited his friend Harry Houdini to attend a seance,with his wife Jean, acting as medium. Jean claimed to have contacted Houdini’s mother and “automatically” wrote a long letter in English. Unfortunately Houdini’s mother had known little English. Consequently the famous magician publicly declared Conan Doyle a fraud.

While Conan Doyle was respected in Spiritualist circles, his blind devotion led him headlong into ridicule on more than one occasion. He was taken in by Frances Griffith and Elsie Wright’s forged photographs of fairies. Conan Doyle, accepting the photographs as authentic, wrote a few pamphlets and The Coming of Fairies (1922), which made him a bit of a laughingstock. Later, Conan Doyle invited his friend Harry Houdini to attend a seance,with his wife Jean, acting as medium. Jean claimed to have contacted Houdini’s mother and “automatically” wrote a long letter in English. Unfortunately Houdini’s mother had known little English. Consequently the famous magician publicly declared Conan Doyle a fraud.