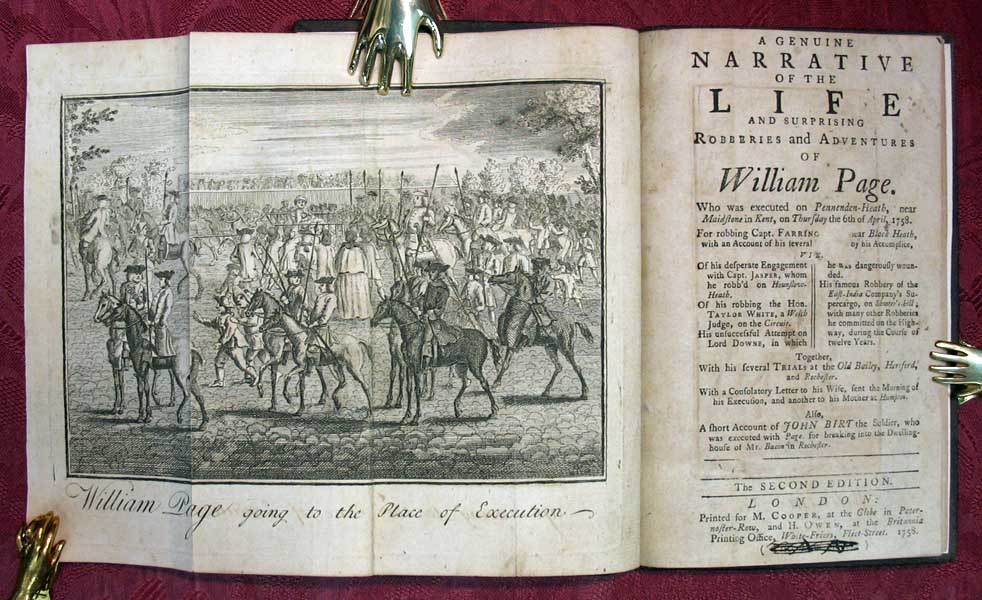

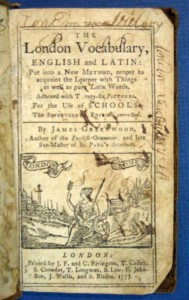

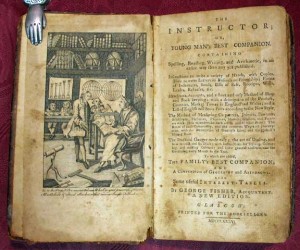

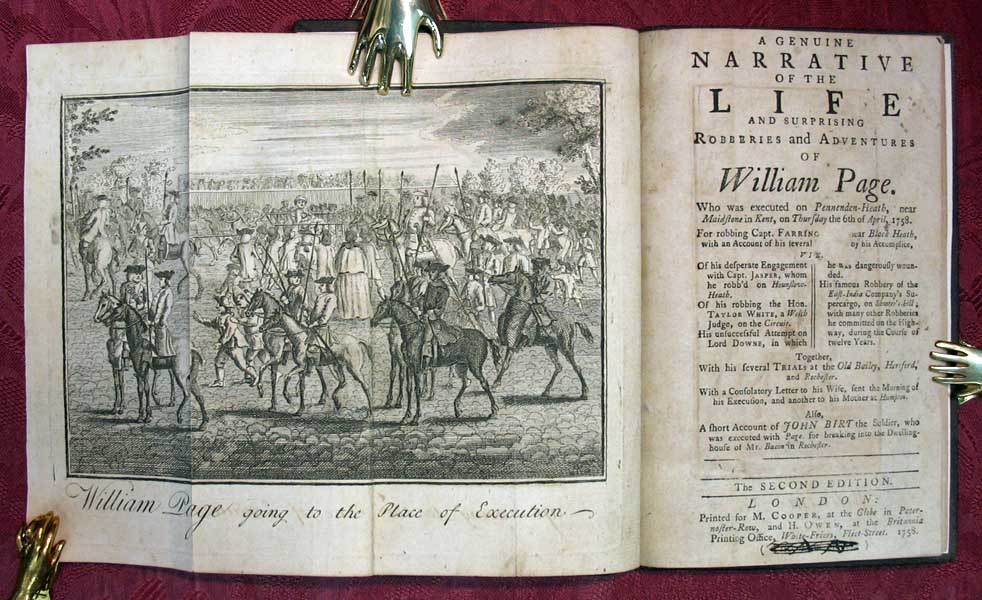

The sensationalization of public executions was a long-standing tradition by Dickens’ day. This account of William Page’s “robberies and adventures” dates to 1758.

On February 24, 1807, three convicted murderers were to be executed at Newgate: Owen Haggerty, John Holloway, and Elizabeth Godfrey. The fact that three people were going to be executed (and one of them a woman) was extremely unusual. The event drew a huge and rowdy crowd. The crowd reached a point of hysteria, and authorities could not even penetrate the throngs to help those caught in the melee. In the end, 27 people died and 70 were sent to the hospital with serious injuries.

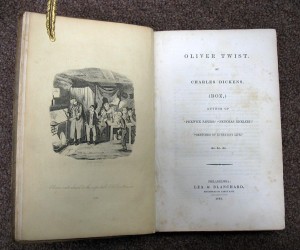

Though that magnitude of injury was unusual, the excitement over public executions certainly was not. By the time Charles Dickens was born five years later, execution as entertainment was firmly entrenched in British culture. Though Dickens, too, would be morbidly fascinated with public executions, he would eventually argue for private executions.

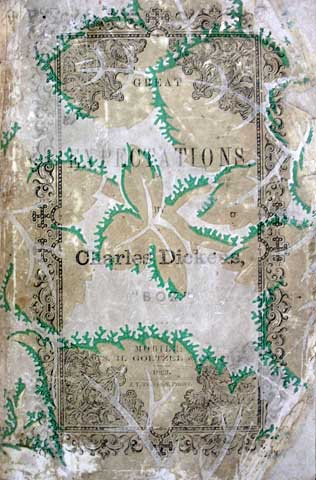

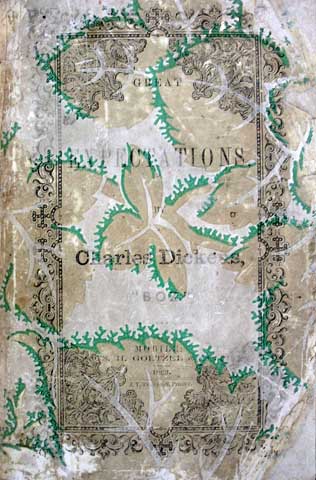

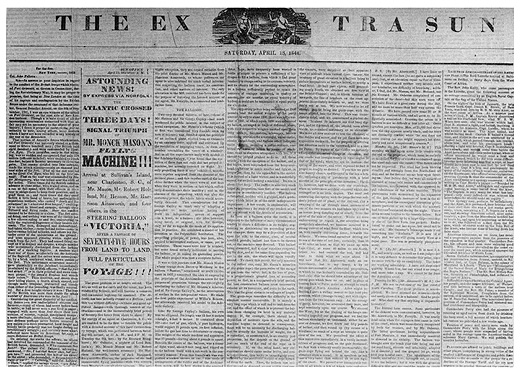

Broadsides Outsell Even Dickens

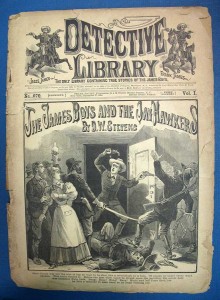

By the 1840’s, Dickens was the most popular novelist in England. His monthly shilling numbers consistently sold in the 10,000’s–quite an impressive figure at the time. But the cheap penny broadsides advertising “popular” murderers regularly outsold Dickens by 100 to one. These accounts often included lurid details of the crimes, partially or completely fabricated by the printers. They were undoubtedly the most widely read material in England and had been for decades.

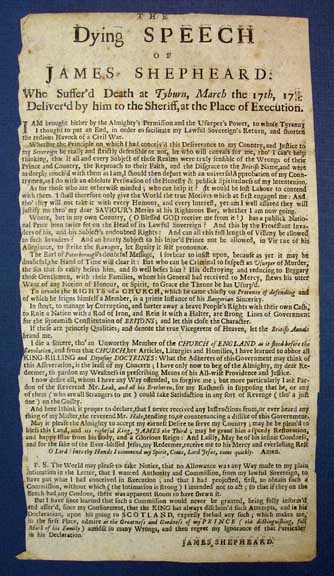

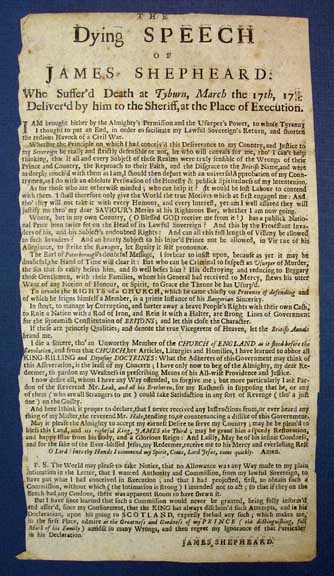

“The Dying Speech of James Shepheard” is known in five different editions. Only four other copies of this one are recorded.

The broadsides fueled a long-standing obsession with death and criminality. Following execution, it was quite common for Madame Tussaud’s to make wax figures of the deceased. Sometimes Tussaud would even buy clothing and other artifacts from the hangman to make the wax figure more realistic. Death masks were also sometimes made. In the case of William Corder, who was hanged on August 11, 1828 for the “Red Barn Murder” of Maria Marten, a cast was taken of Corder’s face and a copy of a book about the trial was bound in Corder’s own skin. William Burke’s death mask, taken on January 28, 1829 clearly shows an indentation from the noose on Burke’s neck. Phrenology, the study of the skull’s shape as a guide to one’s personality, was all the rage in the nineteenth century, and people were enthusiastically interested in studying the skulls of criminals.

But undoubtedly the most prurient and popular entertainment was attending the execution itself. Ordinary citizens would walk miles to attend executions. In smaller towns, executions would be held on market days to facilitate attendance. By the 1850’s, special trains had actually been laid on to transport people to executions. School groups were even made to attend executions as morality lessons; the rationale was that watching such a brutal punishment would deter spectators from committing the same crimes.

Dickens Attends His First Execution

Dickens worked as a court reporter from 1829 to 1833, a position that exposed him to the world of criminals and capital punishment. This experience likely had a significant impact on Dickens’ attitude toward crime, punishment, and justice. But the first execution that we know Dickens attended was that of Francois Benjamin Courvoisier, on July 6, 1840. By this time, it was not fashionable for nobility to attend executions, but Courvoisier’s case was an exception: he’d been convicted of murdering Lord William Russell. Over 40,000 people attended the execution, including William Makepeace Thackeray. Profoundly disgusted by the experience, Thackeray would later describe the experience in great detail in “Going to See a Man Hanged.”

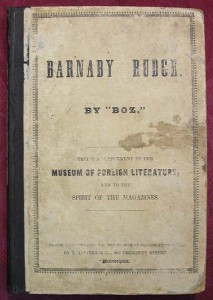

Dickens seemed more inured to the event, but he later said in a letter that he witnessed “No sorrow, no salutary terror, no abhorrence, no seriousness; nothing by ribaldry, debauchery, levity, drunkenness, and flaunting vice in fifty other shapes.” Experts hypothesize that seeing this execution influenced Dickens’ portrayal of the bloodthirsty hangman Ned Dennis in Barnaby Rudge, published in 1841.

Dickens seemed more inured to the event, but he later said in a letter that he witnessed “No sorrow, no salutary terror, no abhorrence, no seriousness; nothing by ribaldry, debauchery, levity, drunkenness, and flaunting vice in fifty other shapes.” Experts hypothesize that seeing this execution influenced Dickens’ portrayal of the bloodthirsty hangman Ned Dennis in Barnaby Rudge, published in 1841.

That same year, Dickens tried to reach an agreement with Mackey Napier, editor at the Edinburgh Review. The two had met during Dickens’ visit to Scotland, and Napier had invited Dickens to write a piece for the journal. Such invitations were difficult to come by; the Review was the premier intellectual publication at the time. But the Review was also definitively a definitively conservative, Whig publication, quite at odds with Dickens’ own politics. He proposed a number of ideas, including a piece about the sordid state of public executions, even conducting substantial research on the topic.

Ultimately Dickens decided that the Edinburgh Review wasn’t a great fit for him. Five years later, he published a series of letters in the Daily News, a periodical dedicated to “free trade” politics. Dickens remained editor of the paper for only twenty days, but he published five letters on capital punishment during and after his tenure. Critics argue that it’s the best-researched and -written non-fiction that Dickens ever wrote. He addresses Courvoisier’s execution in the second letter. In the Daily News letters, Dickens speaks out against the death penalty altogether.

The Manning Executions

But Dickens managed to attend yet another sensational execution on November 13, 1849. Maria and Frederick Manning were executed at Horsemonger Lane Gaol in front of a crowd that numbered between 30,000 and 50,000. Executions at Horsemonger Lane were particularly popular spectacles; the gallows were on the rooftop. It was said that on execution days, local tenants could let the rooms with windows facing the gaol. Dickens rented such quarters and held a late dinner party there on the night before the execution. He walked around and observed the crowd afterward.

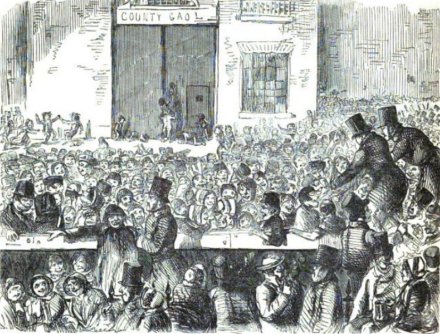

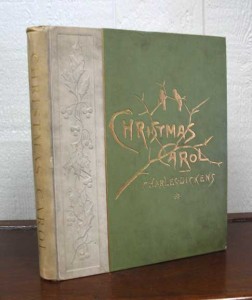

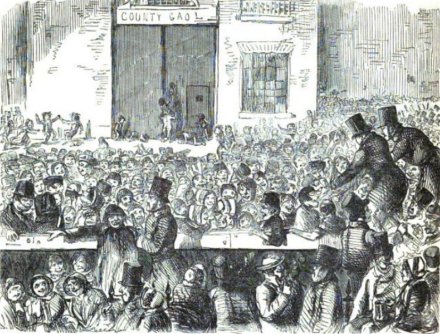

John Leech’s “Great Moral Lesson at Horsemonger Lane Gaol” appeared in ‘Punch’ magazine after the Manning execution and turned a critical eye not to the gallows, but to the crowd below. Leech, who had illustrated ‘A Christmas Carol,’ attended the execution with Dickens.

Tormented by the thought of a mad crowd, Maria Manning tried to stab herself in the throat with her own fingernails the day before her execution. Thwarted, she appeared before the mob in an elegant black satin gown and veil. Her outfit merited mention from countless spectators, including Dickens, and black satin remained out of style for the next thirty years. Dickens shares his recollections of the public hanging in an 1852 essay called “Lying Awake,” which appeared in Household Words. And he evokes Maria Manning in Bleak House’s Mademoiselle Hortense. Dickens also wrote a letter to The Times about the appalling scene at the execution. His letter did much to raise interest in the abolitionist cause. Meanwhile, abolitionist George Jacob Holyoake wrote an ironic commentary in his journal The Reasoner, decrying the unchecked crowding at executions.

But opponents defended the execution circus, arguing that it was a public duty to make the criminals’ last moments as miserable as possible. One proponent wrote, “The merciful object of ever punishment which the law inflicts is not so much to revenge past crime as to prevent its recurrence”; that is, capital punishment was necessary because it deterred spectators from committing the same crimes. Such a mindset was hardly contained among the uneducated. Even clergymen could get overzealous. One inflicted serious burns on a female inmate after holding her hand over a candle to simulate the fires of Hell that awaited if she didn’t repent.

Grisly Executions Sway Public Opinion

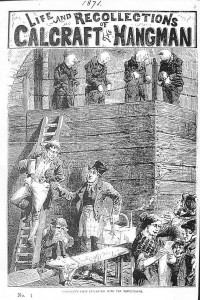

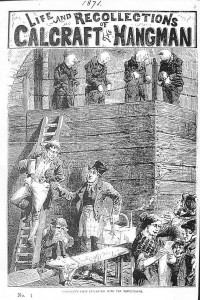

The most famous hangman of the 19th century, William Calcraft completed around 450 executions. An illustrated account of his life was published in 1871.

While Dickens consistently comments on the horrors of executions, that didn’t dissuade him from attending more. In Pictures from Italy (1846), Dickens describes in graphic detail a guillotining he watched in Rome. He observed that the “ugly, filthy, careless, sickening spectacle” showcased the very worse of humanity. And he recounts another beheading, this time in Switzerland, in Household Words. These passages certainly made a mark on public opinion.

So did the grisly execution of John Gleeson Wilson on September 15, 1849. Around 100,000 people came to Kirkdale to witness the spectacle. The case had received so much attention, broadside publishers had changed the name of the street where the crime occurred to curb publicity. Unfortunately or both Wilson and the spectators, accomplished executioner William Calcraft was indisposed. He’d been replaced by a seventy year old with little experience. Calcraft’s substitute made the drop too short, and he didn’t pull the cape down far enough; Wilson’s face was exposed to the crowd. Rather than having his neck immediately broken, Wilson strangled to death–and it took a full fifteen minutes. Spectators watched in horror as his eyes bulged and his face turned purple. Numerous individuals fainted at the sight.

Abolitionists Gain Considerable Traction

Throughout the 1850’s, the abolitionists gained more sympathy. It fell completely out of fashion for both nobility and the upper middle classes to attend executions. But while more and more people were coming to believe that the death penalty should be eliminated, Dickens’ sentiments were swinging the opposite way. He’d lobbied for complete abolition of the death penalty in the late 1840’s. But in 1859, upon hearing about the potential reprieve of convicted murderer Thomas Smeghurst, Dickens wrote “I would hang any home secretary, Whig, Tory, Radical, or otherwise, who would step in between so black a scoundrel and the gallows.”

He confirmed this stance in 1864, admitting, “I should be glad to abolish both [public executions and capital punishment] if I knew what to do with the Savages of civilization. As I do not, I would rid Society of them, when they shed blood, in a very solemn manner but would bar out the present audience.” Thus Dickens came to support the death penalty in cases of violent crime, which was concurrent with English law at the time. In 1861, the Criminal Law Consolidation Act reduced capital offenses to murder, high treason, piracy, and arson in a Royal Dockyard. Other than one case of attempted murder, no one had been executed for any other offenses since 1837, so the law finally caught up to common practice.

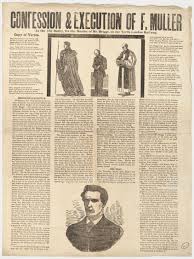

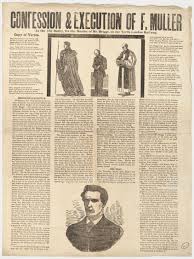

As Britain’s first “railway murderer,” Franz Muller drew considerable attention.

On November 14, 1864, over 100,000 people gathered to watch the execution of Franz Muller. The King of Prussia had written a letter to Queen Elizabeth on Muller’s behalf, but to no avail. The German tailor had been convicted of killing banker Thomas Brigg. Brigg’s colleagues had discovered bloody clothing and hat in Brigg’s compartment, and the man was found on the railroad tracks shortly thereafter. He was still carrying a considerable amount of money, but his pocket watch and chain had been stolen.

The bloody hat had been traced directly back to Muller, while the pocket watch turned up at a local pawn shop. The proprietor said that a man with a German accent had brought it. By this time, Muller had already boarded a steamship for New York. The inspector boarded a faster ship, intercepted Muller in New York, and returned him to England. Muller was found guilty in less than fifteen minutes.

At the time, people were especially preoccupied with the safety of rail travel. The crowd was boisterous on execution day. Multiple people were violently trampled to death, including a woman and her infant. By this time, public opinion had shifted; Victorians were more evenly divided over the efficacy of public executions. Abolitionists pointed out all the crime that occurred in the very shadow of the gallows. They commonly quote a chaplain’s report that of 167 criminals he’d interviewed on execution day, only three had never witnessed a public execution. Clearly this form of punishment did not deter future criminal behavior.

Legendary Authors Influence Legislation

Along with the Quakers, both Thackeray and Dickens would be credited with changing public opinion on capital punishment. The 1864 Royal Commission on Capital Punishment spent two years deliberating on the issue and finally ruled that there was no case for ending the death penalty altogether. But they did decide to make executions private. On May 11, 1868, the Capital Punishment Amendment was read into Parliament.

A number of factors led to changes in England’s capital punishment laws, but we shouldn’t underestimate Dickens’ role in changing public opinion. The Inimitable One consistently exerted an uncanny influence over his contemporary readers.

Related Posts:

A Brief History of True Crime Literature

Charles Dickens the Copyright Confederate

Andersen’s Visit with Dickens Less Than a Fairy Tale

Thanks for reading! Love our blog? Subscribe via email (right sidebar) or sign up for our newsletter--you’ll never miss a post.

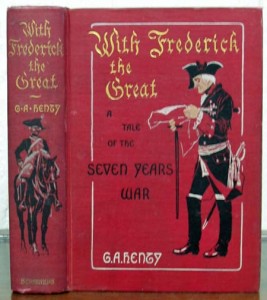

The late nineteenth century was truly a golden age in children’s literature. As the concept of childhood evolved, didacticism fell out of style and children’s authors focused more on stimulating their readers’ imaginations with exciting, engaging tales. George Alfred Henty was one of the most popular figures of the era. His historical adventure stories appealed to both children and young adults, but Henty was a controversial figure even in his own time.

The late nineteenth century was truly a golden age in children’s literature. As the concept of childhood evolved, didacticism fell out of style and children’s authors focused more on stimulating their readers’ imaginations with exciting, engaging tales. George Alfred Henty was one of the most popular figures of the era. His historical adventure stories appealed to both children and young adults, but Henty was a controversial figure even in his own time. Seeing little promise of promotion, Henty resigned from the Army in 1859. He married Elizabeth Finucane shortly thereafter, but the union would be a short one; Elizabeth died in 1865 after a long illness. Left with children and unsure of his career path, Henty decided to begin writing for the Standard newspaper. By 1866, he was working as a special correspondent. During his career, Henty would cover the Franco-Prussian War; the Carlist Rebellion in Spain; the Turco-Serbian War; the opening of the Suez Canal; and the Dreyfus Trial.

Seeing little promise of promotion, Henty resigned from the Army in 1859. He married Elizabeth Finucane shortly thereafter, but the union would be a short one; Elizabeth died in 1865 after a long illness. Left with children and unsure of his career path, Henty decided to begin writing for the Standard newspaper. By 1866, he was working as a special correspondent. During his career, Henty would cover the Franco-Prussian War; the Carlist Rebellion in Spain; the Turco-Serbian War; the opening of the Suez Canal; and the Dreyfus Trial. During his own lifetime Henty was frequently accused of being xenophobic and racist. An enthusiastic imperialist, Henty also drew criticism for glorifying British imperialism. His In the Reign of Terror (1888) and No Surrender! A Tale of the Rising in La Vendee (1900) were decidedly hostile toward the patriots of the French Revolution, and in True to the Old Flag (1885), Henty took a Loyalist stance regarding the American Revolutionary War. With Lee in Virginia (1890) also raised eyebrows for supporting the “aristocratic” Confederacy of the Civil War.

During his own lifetime Henty was frequently accused of being xenophobic and racist. An enthusiastic imperialist, Henty also drew criticism for glorifying British imperialism. His In the Reign of Terror (1888) and No Surrender! A Tale of the Rising in La Vendee (1900) were decidedly hostile toward the patriots of the French Revolution, and in True to the Old Flag (1885), Henty took a Loyalist stance regarding the American Revolutionary War. With Lee in Virginia (1890) also raised eyebrows for supporting the “aristocratic” Confederacy of the Civil War.

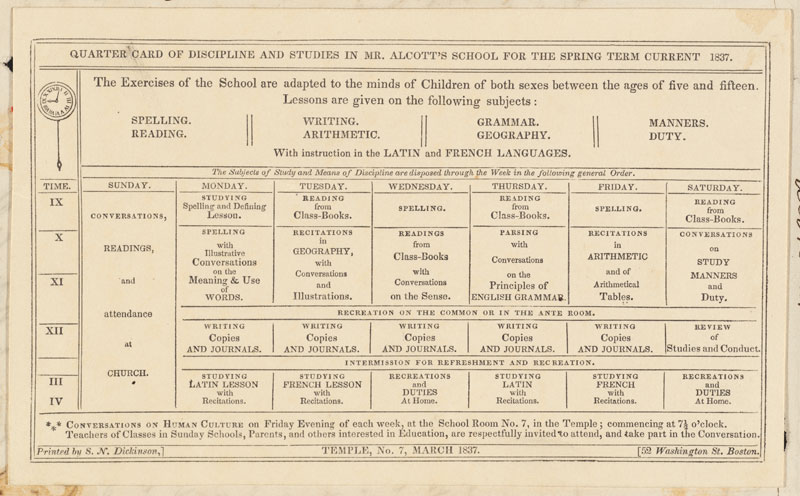

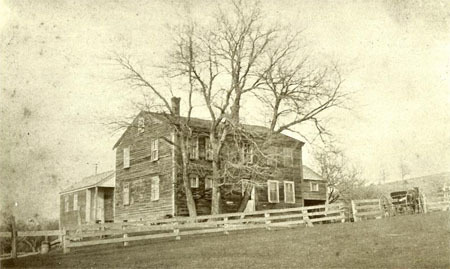

Because Little Women was so obviously based on Alcott’s own childhood, her family gained celebrity along with her. Bronson was quite fond of the attention. Now wealthy and widowed, he sported fine clothes and toured the country as “The Father of the Little Women.” He started publishing (very verbose) volumes of philosophy. Alcott built him the Concord School of Philosophy, so that he could again enjoy lecturing to an audience. His exploits were curtailed by a stroke, and he was forced to retire to a beautiful home in Louisburg Square, provided by his dutiful daughter, who visited almost every day. Alcott, however, wanted nothing to do with fame–perhaps because she saw so little merit in the books that had made her famous. Tourists shamelessly came calling at Orchard House, and Alcott would often pretend to be her own maid to avoid their attentions.

Because Little Women was so obviously based on Alcott’s own childhood, her family gained celebrity along with her. Bronson was quite fond of the attention. Now wealthy and widowed, he sported fine clothes and toured the country as “The Father of the Little Women.” He started publishing (very verbose) volumes of philosophy. Alcott built him the Concord School of Philosophy, so that he could again enjoy lecturing to an audience. His exploits were curtailed by a stroke, and he was forced to retire to a beautiful home in Louisburg Square, provided by his dutiful daughter, who visited almost every day. Alcott, however, wanted nothing to do with fame–perhaps because she saw so little merit in the books that had made her famous. Tourists shamelessly came calling at Orchard House, and Alcott would often pretend to be her own maid to avoid their attentions.