Unique.

A compelling word, and one that certainly can, and should, stand on its own, though frequently we find unnecessary modifiers employed to make the unique even more so, if such is at all possible… more unique, highly unique, uniquely unique…. you get the drift.

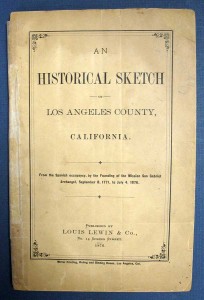

So with this in mind then, and without modifying hyperbole, we issue this list for June, wherein each of the 60 items displays an aspect of uniqueness… whether by definition, inscription or perhaps being the only copy on the market. As is our practice, the list is eclectic in nature- from air to water, original art to original mss, from Nevada to Massachusetts. Temporally, the items reach back to the 1770s, and continue on until the mid-20th C. Prices range from $75 to $7500.

Winning Independence: An Illustrated Address Describing the “Parlor Profession”

Niles Bryant, the President & Founder of the Niles Bryant School of Piano Tuning, and enjoys some recognition in the music world for his 1906 publication, Tuning, Care and Repair of Reed and Pipe Organs, which was reissued in 1968 by Vestal Press. “Through the profession of piano tuning, I offer you indestructible resources, good fortune and permanent independence.” So Bryant opens this publication, which is a promotional piece for the profession of piano tuning, and even more specifically, the advantages of attending his school to learn the profession, as well as to puff his invention, “The Tune-a-Phone”. This publication is tot located on OCLC, nor found in the NUC. Details>>

Niles Bryant, the President & Founder of the Niles Bryant School of Piano Tuning, and enjoys some recognition in the music world for his 1906 publication, Tuning, Care and Repair of Reed and Pipe Organs, which was reissued in 1968 by Vestal Press. “Through the profession of piano tuning, I offer you indestructible resources, good fortune and permanent independence.” So Bryant opens this publication, which is a promotional piece for the profession of piano tuning, and even more specifically, the advantages of attending his school to learn the profession, as well as to puff his invention, “The Tune-a-Phone”. This publication is tot located on OCLC, nor found in the NUC. Details>>

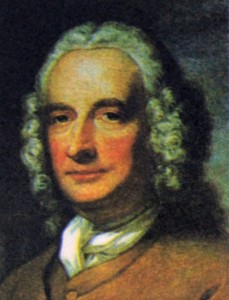

Mr. Thackeray, Mr. Yates, and the Garrick Club Affair

The notorious quarrel between two of England’s most popular authors began with Yates’ critical review, in Town Talk, of Thackeray’s English Humourists of the Eighteenth Century. Thackeray, as might be expected, was a bit affronted at what he viewed as a slanderous insult by this fellow member of the Garrick Club; believing much of Yates’ information came from club meetings, he took his grievance to the club committee. The committee sided with Thackeray and instructed Yates to apologize. Yates refused and was forcibly barred from club premises, subsequently bringing charges against the club Secretary.

The notorious quarrel between two of England’s most popular authors began with Yates’ critical review, in Town Talk, of Thackeray’s English Humourists of the Eighteenth Century. Thackeray, as might be expected, was a bit affronted at what he viewed as a slanderous insult by this fellow member of the Garrick Club; believing much of Yates’ information came from club meetings, he took his grievance to the club committee. The committee sided with Thackeray and instructed Yates to apologize. Yates refused and was forcibly barred from club premises, subsequently bringing charges against the club Secretary.

Charles Dickens, absent from London as this brouhaha was brewing, returned to find all in full force. He offered to mediate, though primarily siding with Yates, which Thackeray viewed as treachery. The ill feelings between the two did not abate for years, until shortly before Thackeray’s death in 1863. (More about the Garrick Club Affair>>)

Herein Yates recounts the history and evidence of the disagreement, with, not unexpectedly, a bias to his own case. This copy was presented to Edward Bradley, presumed to be the Victorian novelist, who wrote under the pen name Cuthbert M. Bede. Known in Wise facsimiles (cf Todd 425c), the first edition, as here, has been just twice at auction in the last 30+ years, the last being 1977. It’s a rare piece of Dickensiana; this is the first time we’ve ever been able to offer the item. Details>>

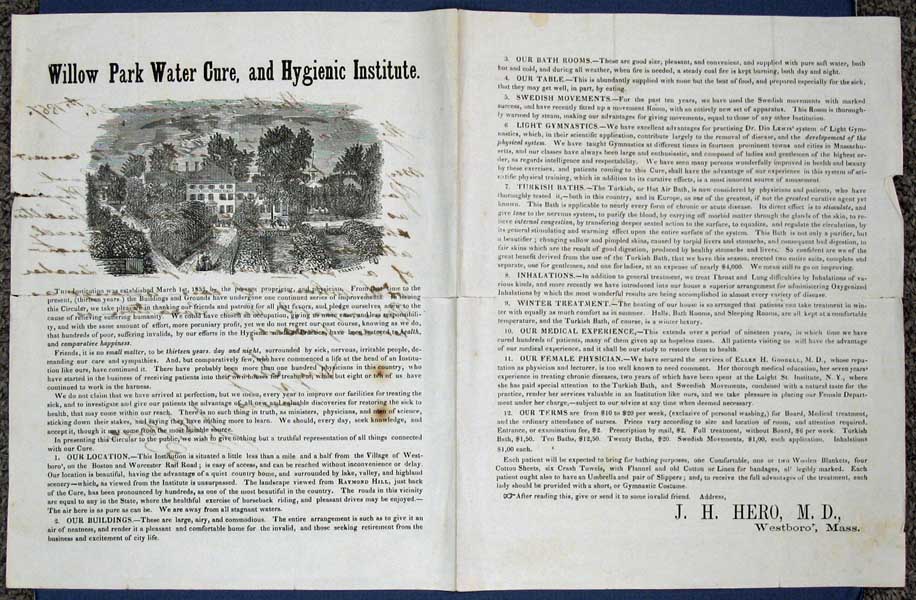

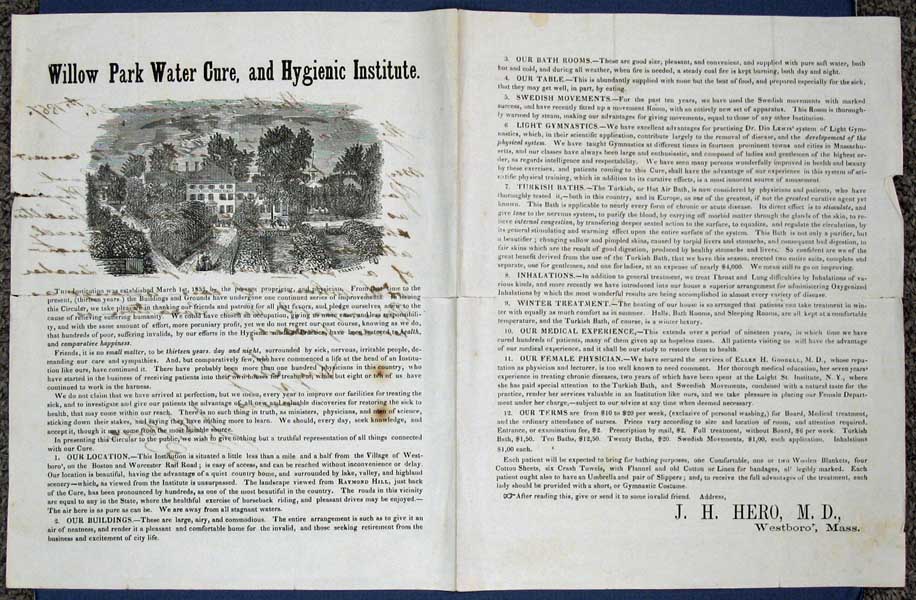

Willow Park Water Cure, and Hygienic Institute

On March 1, 1853, John Henry Hero established the Willow Park Water Cure, with himself as proprietor and attending physician, for the treatment of chronic diseases through the “water cure.” Treatments of Swedish movements, light gymnastics, Turkish baths, and inhalations were also employed, to considerable success–though this success did not come without a personal price; as Hero writes in this circular “Friends, it is no small matter, to be thirteen years, day and night, surrounded by sick, nervous, irritable people, demanding our care and sympathies.” Hero seeks a change, and it is to this latter Hero addresses himself in this circular’s holograph letter: “I intend to convert / my Institution into a School / for young Ladies.” Later in the year, Dr. Hero did found the Willow Park Seminary for young women “where the Physical as well as the Intellectual facilities [were] faithfully and equally attended to.” OCLC does not record this particular broadside, though two others are found, each in one copy only. Details>>

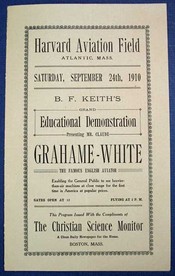

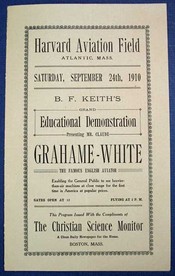

BF Keith’s Grand Educational Demonstration

Claude Grahame-White was the Glamour Boy of early aviation, somewhat of a playboy, with no engineering background whatsoever, Grahame-White became enamored of flying when, in 1908, he saw the Wright’s demonstrate their invention to the French crowds at Camp d’Auvours. Within a relatively short time, self-taught, Grahame-White soloed without a formal lesson. He quickly made a name for himself as a dashing aviator. In 1910, JV Martin of the Harvard Aeronautical Society, invited him to compete in the first Boston-Harvard Meet. With the promise of a $50,000 retainer & expenses, Grahame-White accepted. Grahame-White won that one, and others, as he thrilled spectators with his races & aerial exhibitions such as that announced in this “One-man Show” program.

Claude Grahame-White was the Glamour Boy of early aviation, somewhat of a playboy, with no engineering background whatsoever, Grahame-White became enamored of flying when, in 1908, he saw the Wright’s demonstrate their invention to the French crowds at Camp d’Auvours. Within a relatively short time, self-taught, Grahame-White soloed without a formal lesson. He quickly made a name for himself as a dashing aviator. In 1910, JV Martin of the Harvard Aeronautical Society, invited him to compete in the first Boston-Harvard Meet. With the promise of a $50,000 retainer & expenses, Grahame-White accepted. Grahame-White won that one, and others, as he thrilled spectators with his races & aerial exhibitions such as that announced in this “One-man Show” program.

This rare survivor lists the diverse aerial stunts to be performed by Grahame-White during the day… “With the Bleriot Monoplane” includes a dive from 4000 feet “with engine stopped.” “With the Farman Biplane,” the twelve planned events include “Aerial switchback flying”; “The corkscrew glide [spin?] from a high altitude”; and “Knocking down ninepins placed on the ground, without alighting.” With this sort of exhibition, and his dashing and flamboyant personality, the handsome Grahame-White gave the new aviation field, previously dominated by engineers, something that had been lacking to date: a ‘sexy’ nature. Details>>

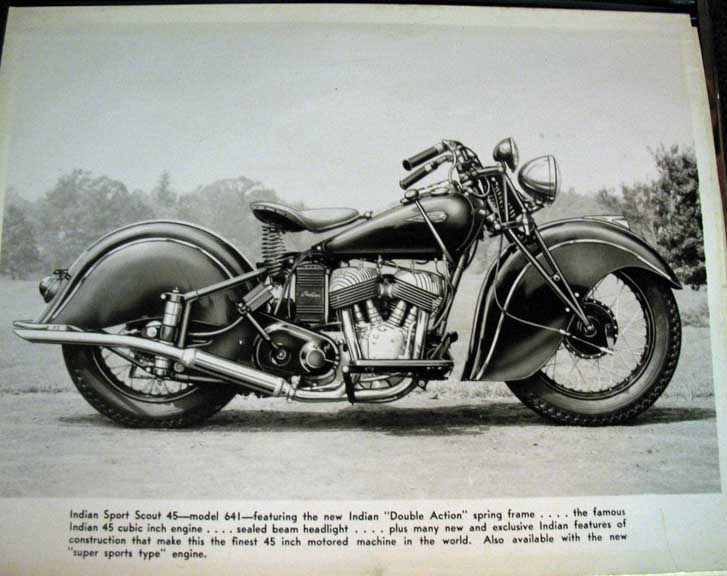

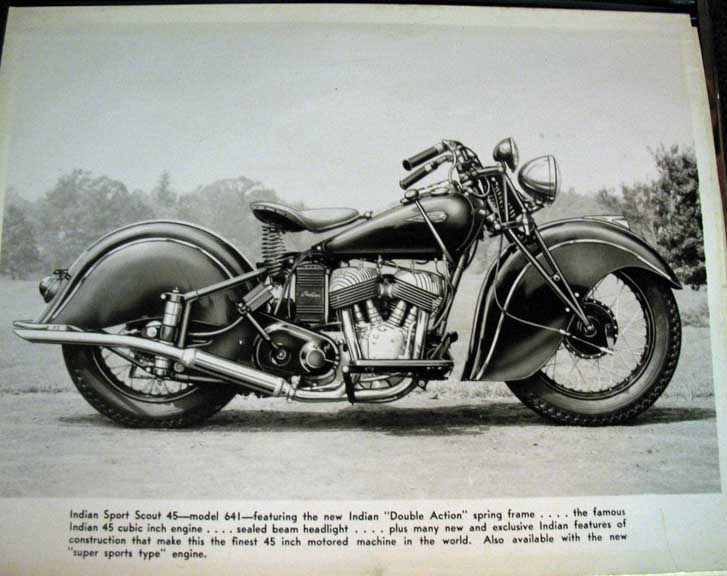

Salesman’s Album with Sixty Photographic Images of Indian Motorcycles

This a presumed company-issued production, no doubt targeted for those who already owned an Indian Motorcycle franchise, or generated for traveling company reps, allowing prospective buyers, such as police departments, to view the entire product line. We find no bibliographical record of another such album being offered, and believe the album to have been produced in limited numbers.

In 1940, Indian sold nearly as many motorcycles as its major rival, Harley-Davidson. At the time, Indian represented the only true American-made heavyweight cruiser alternative to Harley-Davidson. Indian’s most popular models were the Scout, made from 1920 to 1946, and the Chief, made from 1922 to 1953. Unfortunately, the company went bankrupt in 1953. Today, the vintage cycle enjoys much popularity amongst enthusiasts, with models from the era displayed herein being offered for five-figure sums. A fascinating and well-preserved original photograph album, which visually documents the late ’30s and early ’40s Indian Motorcycle company, and its impressive product line, as existed during the company’s heyday. Details>>

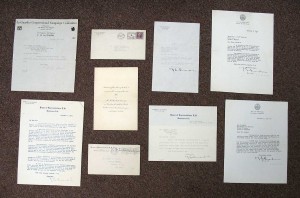

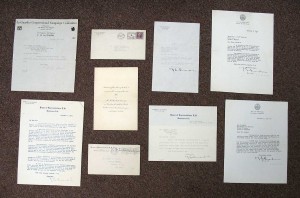

Correspondence, Including LaGuardia’s Wedding Invitation

Fiorello LaGuardia, or “Little Flower,” is widely regarded as one of the best mayors in New York City history, whose tenure redefined the office. He was the 99th mayor of the “Big Apple”, serving his populace from 1934 to 1945. For those twelve years, the 5’2″, sometimes belligerent, chief executive dominated life in New York City as if he was 7″2′. Unlike many politicians today, he fulfilled many of his pledges, especially the ferreting out of corruption in the city’s government. Such earned him a reputation for placing the city’s interests ahead of political considerations, and in the same vein, although technically a Republican, he worked closely with the New Deal administration of President Franklin Roosevelt to secure funding for large public works projects. These federal subsidies enabled New York City to create a transportation network the envy of the world, and to build parks, low-income housing, bridges, schools, & hospitals. Furthermore, he achieved the unification of the city’s rapid transit system, a goal that had long eluded his predecessors, and he reformed the structure of city government by pushing for a new City Charter. LaGuardia presided over construction of New York City’s first municipal airport on Flushing Bay, later to become his namesake. As a result of all his efforts, LaGuardia’s psychological effect on New York City was nothing short of profound, restoring faith in city government by demanding excellence from civil servants. Details>>

Fiorello LaGuardia, or “Little Flower,” is widely regarded as one of the best mayors in New York City history, whose tenure redefined the office. He was the 99th mayor of the “Big Apple”, serving his populace from 1934 to 1945. For those twelve years, the 5’2″, sometimes belligerent, chief executive dominated life in New York City as if he was 7″2′. Unlike many politicians today, he fulfilled many of his pledges, especially the ferreting out of corruption in the city’s government. Such earned him a reputation for placing the city’s interests ahead of political considerations, and in the same vein, although technically a Republican, he worked closely with the New Deal administration of President Franklin Roosevelt to secure funding for large public works projects. These federal subsidies enabled New York City to create a transportation network the envy of the world, and to build parks, low-income housing, bridges, schools, & hospitals. Furthermore, he achieved the unification of the city’s rapid transit system, a goal that had long eluded his predecessors, and he reformed the structure of city government by pushing for a new City Charter. LaGuardia presided over construction of New York City’s first municipal airport on Flushing Bay, later to become his namesake. As a result of all his efforts, LaGuardia’s psychological effect on New York City was nothing short of profound, restoring faith in city government by demanding excellence from civil servants. Details>>

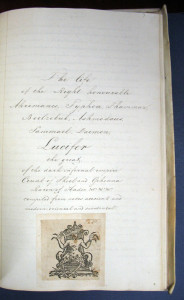

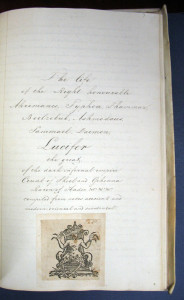

The Life of The Right Honourable Arimanes, Typhon, Thammuz, Beelzebub, Ashmodaus, Sammael, Daemon, Lucifer the Great, of the Dark Infernal Empire Count of Sheol and Gehenna, Baron of Hades &c., &c., &c

This eighteenth-century codex is an entirely holograph history of Lucifer, wherein the anonymous author tells us in his Preface, “Lucifer … is a spiritual being. That is true; but far from being considered here in that light, he is represented plainly terrestrial. He is not the Lucifer as Vondel, Milton and Klopstock described him, but exactly as he is shown in magick lanthorns for the amusement of the spectators. … My Lucifer is of Ethereal breed and Ether is and remains material. …. mine is of a persian and chaldean race.”

This eighteenth-century codex is an entirely holograph history of Lucifer, wherein the anonymous author tells us in his Preface, “Lucifer … is a spiritual being. That is true; but far from being considered here in that light, he is represented plainly terrestrial. He is not the Lucifer as Vondel, Milton and Klopstock described him, but exactly as he is shown in magick lanthorns for the amusement of the spectators. … My Lucifer is of Ethereal breed and Ether is and remains material. …. mine is of a persian and chaldean race.”

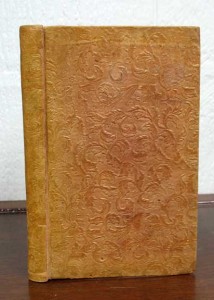

Though the volume bears no date, it bears the Pro Patria “Maid of Dort” watermark, circa 1760’s. Affixed under the holograph title is an extracted woodcut image [ca 1550, cf. Sebastian MŸnster’s “Cosmographia” (1544)] of the ‘God Deumo (Demus or Deumus) of Calicut.’ The volume has a full vellum binding and yapp edges. Details>>

Thanks for reading! Love our blog? Subscribe via email (right sidebar) or sign up for our newsletter--you’ll never miss a post.