“I love to have a martini, two at the very most. Three and I’m under the table…

Four and I’m under the host!”

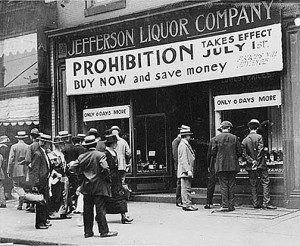

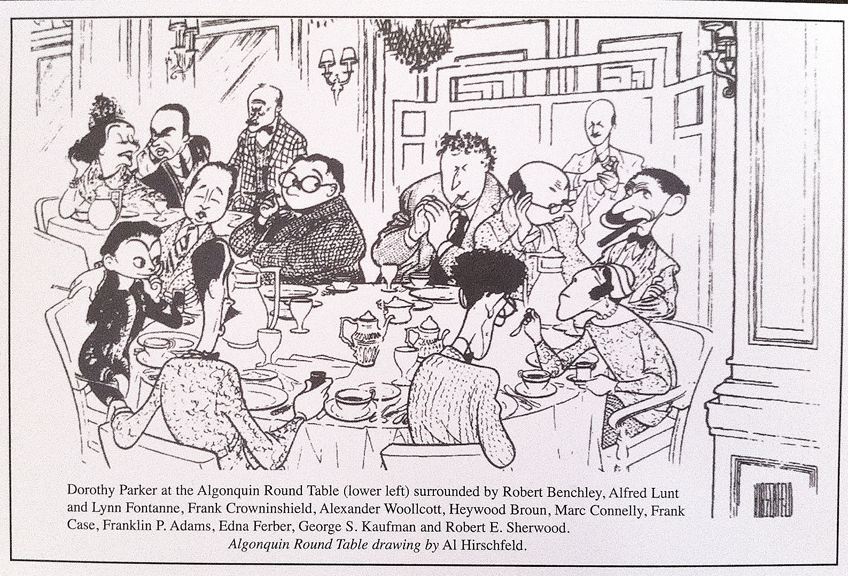

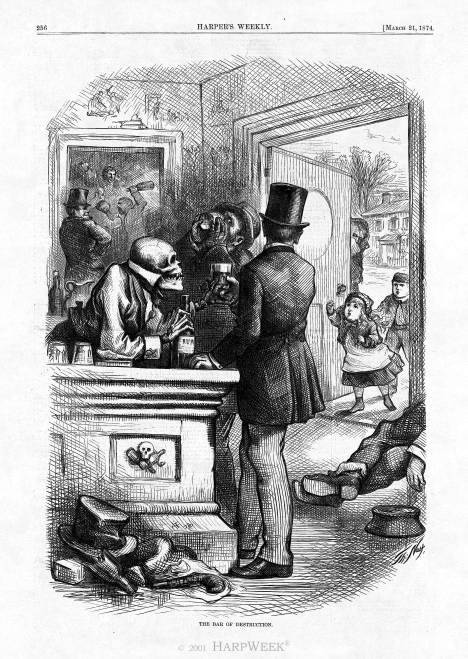

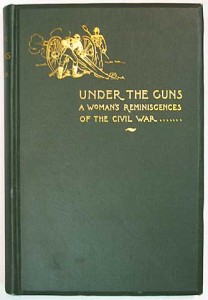

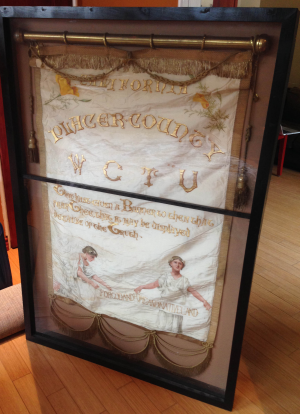

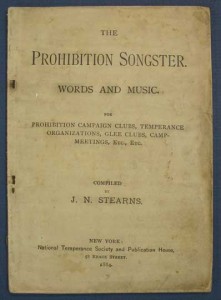

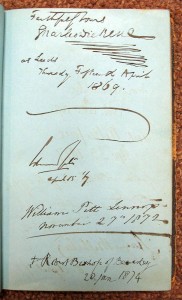

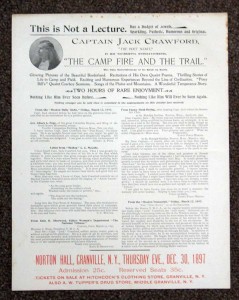

Though we don’t expect you all to know this, we recently acquired (in collaboration with The Book Shop, LLC) a large collection of Temperance-related material. We have songbooks, cookbooks, pamphlets, announcements, postcards – all devoted to the righteous Temperance movement! The sheer amount of information on the dangers of alcohol got us thinking about the Prohibition and the 1920s. How was the lifestyle of some of the literary geniuses of “the day” influenced by the government’s chains? More specifically, did it actually affect the writing of the “Algonquin Round Table” – a group of popular and (usually) similar-minded 1920s authors, playwrights, actresses & editors who met daily at New York’s Hotel Algonquin and traded barbs, insults and witticisms until the entirety of America was aware of their eccentric and deviant lifestyle. The unofficial daily luncheon of the Algonquin table began 1919. Just one year later the Prohibition Ban was instituted, and remained in effect until 1933, long after the “Vicious Circle” had dispersed. Is it merely coincidence that the rise of the group known for their wit and sharp tongues coincides with the onset of a strict government law? Or did interference of administration in the personal lives of the American people somehow help these writers achieve the greatness they were to be known for?

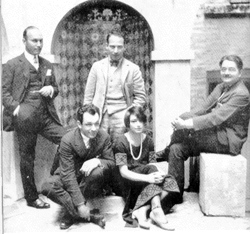

Art Samuels, Charles MacArthur, Harpo Marx, Dorothy Parker & Alexander Woollcott – some of the founding members of the Algonquin Round Table or the “Vicious Circle” as they came to be known.

As to a small background on the Algonquin Round Table mentioned above, the members included several well-known names, not only Dorothy Parker but also Robert Benchley, Franklin Pierce Adams, Marc Connelly, Ruth Hale, Robert E. Sherwood, John Peter Toohey, Harold Ross (founder of The New Yorker magazine), Harpo Marx, Edna Ferber & Alexander Woollcott. Other members drifted in-and-out of the original circle throughout the years. The daily luncheon was not the only interaction of these people, however. They constantly wove through each other’s circles, working together, playing together, writing together… basically they never left each other’s sides (or stayed out of each other’s personal lives, it seems). What does the Prohibition have to do with the Vicious Circle, you may ask?

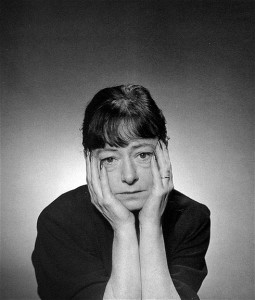

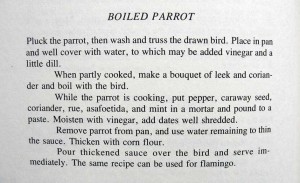

Kathleen Morgan Drowne has written a book entitled Spirits of Defiance: National Prohibition and Jazz Age Literature, 1920 – 1933. Not only is it an easy read, it is a fantastic fount of information about the references to the Prohibition and illegal behavior in Jazz Age Literature. She mentions members of the Algonquin Round Table, with a slight focus on Dorothy Parker. Parker, as one of the founders of the Vicious Circle, was becoming well-known for her quick wit, thinly veiled barbs and sardonic one liners (“You can lead a horticulture, but you can’t make her think” is one of the many attributed to Dottie Parker), as well as her often scathing performance reviews, such as the ones she wrote for Vanity Fair at the beginning of her career. It is well-known that members of the Vicious Circle frequented New York speakeasies (of which, throughout the 1920s numbered above 30,000… and no, that is not a typo). Drowne argues that Parker and her contemporaries used speakeasies “as places where their characters willingly make themselves vulnerable to the consequences of law enforcement… important spaces in which they can act outside the law, demonstrate their disdain for outdated behavioral codes, boost their social status in certain circles, and, of course, satisfy their desire to drink… demonstrat[ing] how characters who defy Prohibition by patronizing speakeasies come to see lawbreaking itself as casual – even insignificant- behavior” (Drowne, p. 99). Many of Dorothy Parker’s poems and short stories contain alcohol references (to champagne, “bathtub gin”, and martinis, specifically), and the Algonquin Round Table group were regulars at speakeasies throughout the Prohibition (Dorothy Parker’s signature drink apparently a Johnny Walker whiskey, neat… in case you were wondering). Parker’s slightly crude and roguish attitude towards sex and drinking made her immensely popular at the height of the Jazz Age. Using Parker as an example, you could argue that wit, a sense of humor, a caustic style of writing and an affinity for breaking the rules (the author even divorced in the late 20s) seemed the recipe for success within the Vicious Circle.

Did Prohibition suddenly become an obsolete subject in literature once the repeal was enacted? Of course not! The intense interference of the government in the personal lives of Americans and the fanatical response it triggered in the desperation for alcohol and breaking the rules cannot deny having endured. Times like the magnificent yet seedy house-parties held by Jay Gatsby in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s most famous work were later recalled by authors who wrote about the 30s as full of corruption and alcoholism. Drowne mentions John O’Hara’s 1934 work Appointment in Samarra, for example, and the explicit portrait the writer paints of seedy and unprincipled American following the Prohibition. Not seemingly written as a knock on the repeal, but more as a telling of what government interference in the personal lives of it’s citizens can accomplish in just a few years – a rise in degradation, desperateness, corruption and immoral behavior. Was this the attitude of the Round Table members? Who can tell! Parker went on to Hollywood following the demise of the Algonquin Vicious Circle and wrote screenplays (many of which see actors at bars with a martini, a choice not unnoticed when delving into the psyche of thoughts on alcohol), her love for drink continuing until her death in 1967.

Prohibition was repealed in December of 1933, a few years after the disintegration of the Round Table. Though it caused a good few years of strife in the lives of many average American citizens, it was not to the detriment of all (gangster boss Al Capone reportedly made $60 million a year, untaxed, throughout the Prohibition years). Not only did Al Capone make a splash throughout these years, but perhaps the Prohibition was not the worst thing for these authors to have experienced, seeing as it sharpened their wit & style. Parker’s attitude and behavior (characteristics which one could argue were partially shaped during the Prohibition) were some of the things that made the author so interesting to the general public. In this vein, perhaps the Vicious Circle’s wish to break against the chains of the 1920s and be witty, crude and sometimes even inappropriate is, even if only partially, indebted to the law of Prohibition itself.

Fun Facts About Prohibition:

- 18,000 people CURRENTLY live in “dry counties” throughout the United States, where Prohibition is virtually still in effect! (Who would’ve thought?!)

- Some desperate and rather unfortunate people during Prohibition falsely believed that the undrinkable alcohol in antifreeze could be made safe and drinkable by filtering it through a loaf of bread. It couldn’t.

- In Los Angeles, a jury that had heard a bootlegging case was itself put on trial after it drank the evidence. The jurors argued in their defense that they had simply been sampling the evidence to determine whether or not it contained alcohol, which they determined it did. However, because they consumed all the evidence, the defendant charged with bootlegging had to be acquitted.

- Prohibition, though cutting down on the amount of liquor consumed in many areas of the United States, corresponded with a startling rise in crime in the US, as gangsters fought over bootlegging rights and butted-heads with the US government on many occasions, and regular civilians were put in jail for trying to have a good time. Not only were the gangsters and bootleggers in constant conflict, but the sudden desperate desire for illegal substances placed thousands of lives at stake due to the imperfect or contaminated bootlegged alcohol that was consumed. Thousands died, went blind or were paralyzed from imbibing contaminated bootlegged liquor throughout the United States.

- After Prohibition was repealed (at 4:31pm on December 5th, 1933… not that we’ve been counting the minutes since or anything), President Franklin D. Roosevelt is said to have declared, “What America needs now is a drink.” (ProhibitionRepeal.com)