Karl Marx deeply admired his contemporary Charles Dickens, which should surprise no one familiar with the works of the Inimitable. Dickens used his novels to address the social ills of Victorian society, from the poor conditions in factories to the deplorable treatment of orphans. Some of Dickens’ incredible popularity can certainly be attributed to his overt empathy for the common man, but that same popularity also gave him an unprecedented platform for promoting reform. Dickens took up social causes early in his career and, after the success of Oliver Twist, resolved to use the novel as a vehicle for social commentary.

Sunday Under Three Heads

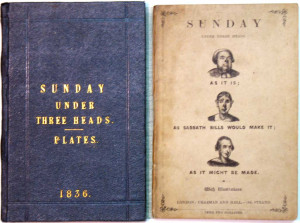

By 1836, England’s social classes were not only divided by economics; they also observed religion differently. For the middle and upper classes, the Sabbath remained a sacred day, free from feasting, visiting, and indulgences. But for members of the lower class, Sunday was usually the only day off and therefore the only day available to make merry. Thus the streets of London were often full of drunkards and revelers on Sundays. Sir Andrew Agnew despised the lower classes to such a degree that he went out of his way to end Sunday festivities with a Sabbath Observances bill. The bill would have put an end to the usual freedoms and entertainments that the lower class usually enjoyed on Sundays. Dickens found the bill draconian and discriminatory. In 1836, he published “Sunday Under Three Heads” under the pseudonym Timothy Sparks. The cartoon illustrates the fact that there could–and should–be some middle ground between reckless revelry and puritanical observance. Dickens would go on to criticize not only Agnew’s bill (which failed to pass in four different permutations, leading Agnew to resign from Parliament), but also his character.

By 1836, England’s social classes were not only divided by economics; they also observed religion differently. For the middle and upper classes, the Sabbath remained a sacred day, free from feasting, visiting, and indulgences. But for members of the lower class, Sunday was usually the only day off and therefore the only day available to make merry. Thus the streets of London were often full of drunkards and revelers on Sundays. Sir Andrew Agnew despised the lower classes to such a degree that he went out of his way to end Sunday festivities with a Sabbath Observances bill. The bill would have put an end to the usual freedoms and entertainments that the lower class usually enjoyed on Sundays. Dickens found the bill draconian and discriminatory. In 1836, he published “Sunday Under Three Heads” under the pseudonym Timothy Sparks. The cartoon illustrates the fact that there could–and should–be some middle ground between reckless revelry and puritanical observance. Dickens would go on to criticize not only Agnew’s bill (which failed to pass in four different permutations, leading Agnew to resign from Parliament), but also his character.

Oliver Twist

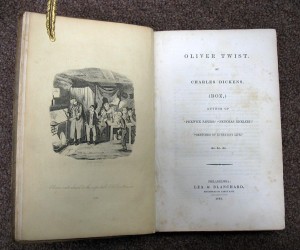

Completed in 1839,  Oliver Twist vaunted Dickens to celebrity status in England. The novel was Dickens’ first to carry over social commentary, and its success galvanized his resolve to use his fiction to address social injustice. Two years prior, in 1837, six members of Parliament and six working men had banded together to publish the People’s Charter (1838). Their aim was to empower working-class men with voting rights and the ability to be elected to the House of Commons. While these demands weren’t new, they were made at just the right time, and the People’s Charter is often regarded as the most famous political manifesto of the nineteenth century. The Chartist movement rapidly emerged, drawing attention to the plight of the working class. Thus Oliver Twist likely could not have been published to a more sympathetic audience. Dickens’ criticism of the Poor Law of 1834 and the horrible conditions of orphanages fell on eager ears.

Oliver Twist vaunted Dickens to celebrity status in England. The novel was Dickens’ first to carry over social commentary, and its success galvanized his resolve to use his fiction to address social injustice. Two years prior, in 1837, six members of Parliament and six working men had banded together to publish the People’s Charter (1838). Their aim was to empower working-class men with voting rights and the ability to be elected to the House of Commons. While these demands weren’t new, they were made at just the right time, and the People’s Charter is often regarded as the most famous political manifesto of the nineteenth century. The Chartist movement rapidly emerged, drawing attention to the plight of the working class. Thus Oliver Twist likely could not have been published to a more sympathetic audience. Dickens’ criticism of the Poor Law of 1834 and the horrible conditions of orphanages fell on eager ears.

A Christmas Carol

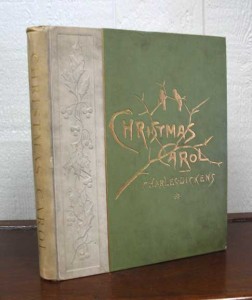

Robert Malthus published An Essay on the Principle of Population pseudonymously in 1798. He argued that overpopulation would necessarily right itself through famine, disease, war or other means. The work was highly influential and immediately raised concerns about the population of Great Britain. In 1800, the Census Act was passed, enabling a census count every ten years. In ensuing decades, the population of cities, and of London in particular, grew astronomically. Malthus’ theory became an excuse to ignore the spread of contagious disease and the lack of proper care for orphans. Dickens personified Malthus in Ebenezer Scrooge, who says, “If they would rather die…they had better do it, and decrease the surplus population.” By this time, another concept dovetailed conveniently with Malthusianism: the “deserving poor.” Victorians commonly believed that people were poor because they deserved to be. In A Christmas Carol, Dickens refutes both ideas wholeheartedly.

Robert Malthus published An Essay on the Principle of Population pseudonymously in 1798. He argued that overpopulation would necessarily right itself through famine, disease, war or other means. The work was highly influential and immediately raised concerns about the population of Great Britain. In 1800, the Census Act was passed, enabling a census count every ten years. In ensuing decades, the population of cities, and of London in particular, grew astronomically. Malthus’ theory became an excuse to ignore the spread of contagious disease and the lack of proper care for orphans. Dickens personified Malthus in Ebenezer Scrooge, who says, “If they would rather die…they had better do it, and decrease the surplus population.” By this time, another concept dovetailed conveniently with Malthusianism: the “deserving poor.” Victorians commonly believed that people were poor because they deserved to be. In A Christmas Carol, Dickens refutes both ideas wholeheartedly.

Bleak House

Critic Terry Eagleton notes that by 1852, Dickens saw Victorian England as “rotting, unravelling, so freighted with meaningless matter that it [was] sinking back into primeval slime.” Bleak House, which Dickens completed in 1853, is widely regarded as England’s first contribution to the tradition of the modern detective novel. But the book still usually gets short shrift among readers and critics. Nevertheless, Bleak House is one of Dickens’ best–and one of his most ambitious in terms of social commentary. Dickens takes on issues of electoral corruption, class division, slum housing, overcrowded urban cemeteries, and the neglect of contagious diseases. More importantly, he draws attention to England’s faulty legal system, as exemplified in the Chancery Court. Prior to his career as an author, Dickens had been a court reporter. The post gave him an inside look at the inconsistencies, inefficiencies, and iniquities of the British court system, and he drew on this experience in Bleak House.

that by 1852, Dickens saw Victorian England as “rotting, unravelling, so freighted with meaningless matter that it [was] sinking back into primeval slime.” Bleak House, which Dickens completed in 1853, is widely regarded as England’s first contribution to the tradition of the modern detective novel. But the book still usually gets short shrift among readers and critics. Nevertheless, Bleak House is one of Dickens’ best–and one of his most ambitious in terms of social commentary. Dickens takes on issues of electoral corruption, class division, slum housing, overcrowded urban cemeteries, and the neglect of contagious diseases. More importantly, he draws attention to England’s faulty legal system, as exemplified in the Chancery Court. Prior to his career as an author, Dickens had been a court reporter. The post gave him an inside look at the inconsistencies, inefficiencies, and iniquities of the British court system, and he drew on this experience in Bleak House.

Hard Times

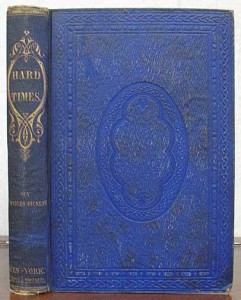

The Anti-Corn Law League was founded in 1836 with the sole purpose of abolishing the Corn Laws, which levied taxes on imported wheat and inflated the price of food at a time when factory owners were attempting to cut wages. After a decade, the movement was successful, and the league disbanded. The movement (known as Manchester capitalism or Manchester liberalism) was based on the principles of laissez-faire capitalism as promoted by Adam Smith, and its members believed that free trade would ultimately lead to a more equitable society. Although Dickens would likely have agreed with the school on other issues like slavery, he vehemently disagreed with laissez-faire capitalism. In Hard Times, we encounter characters whose personal relationships have been tainted by economics and face the cruel living conditions of the urban working class. Dickens also paints a picture of the greedy excesses enabled by unregulated capitalism. Meanwhile, he also addresses contemporary reforms to divorce law, the lack of education for the poor, and the working class’ right to amusement.

The Anti-Corn Law League was founded in 1836 with the sole purpose of abolishing the Corn Laws, which levied taxes on imported wheat and inflated the price of food at a time when factory owners were attempting to cut wages. After a decade, the movement was successful, and the league disbanded. The movement (known as Manchester capitalism or Manchester liberalism) was based on the principles of laissez-faire capitalism as promoted by Adam Smith, and its members believed that free trade would ultimately lead to a more equitable society. Although Dickens would likely have agreed with the school on other issues like slavery, he vehemently disagreed with laissez-faire capitalism. In Hard Times, we encounter characters whose personal relationships have been tainted by economics and face the cruel living conditions of the urban working class. Dickens also paints a picture of the greedy excesses enabled by unregulated capitalism. Meanwhile, he also addresses contemporary reforms to divorce law, the lack of education for the poor, and the working class’ right to amusement.

Dickens is often criticized for failing to offer any solutions to Victorian England’s social issues. Criticism also sways with political trends; in the 1960’s and 1970’s, for instance, Dickens was simply “not Marxist enough.” But ultimately Dickens renders an important service by bringing attention to such a wide range of social concerns, and one must ask whether we should really expect solutions to social problems in our literature.

Related Posts:

Charles Dickens and Capital Punishment

Andersen’s Visit with Dickens Less than a Fairy Tale

Charles Dickens the Copyright Confederate

Why Did Charles Dickens Write Ghost Stories for Christmas?

Jane Bigelow, the First Celebrity Stalker?

Thanks for reading! Love our blog? Subscribe via email (right sidebar) or sign up for our newsletter--you’ll never miss a post.