We know that Wednesday is not everyone’s favorite day of the week. It is neither the beginning of the week, nor the end, and somehow always seems so far from the weekend! We would like to change your opinion for a soft second, however, to respect a civil rights world leader, lawyer, ethicist and philosopher on this particular Wednesday – his birthday – Mahatma Gandhi. In his honor we’d like to share some of his most well-known, well-loved and cherished quotes that give us pause in troubling times.

Happiness is when what you think, what you say, and what you do are in harmony.

A man is but a product of his thoughts. What he thinks he becomes.

Live as if you were to die tomorrow. Learn as if you were to live forever.

Freedom is not worth having if it does not include the freedom to make mistakes.

If I have the belief that I can do it, I shall surely acquire the capacity to do it even if I may not have it at the beginning.

An eye for an eye will make the whole world blind.

The future depends on what you do today.

Earth provides enough to satisfy every man’s needs, but not every man’s greed.

I object to violence because when it appears to do good, the good is only temporary; the evil it does is permanent.

You must not lose faith in humanity. Humanity is like an ocean; if a few drops of the ocean are dirty, the ocean does not become dirty.

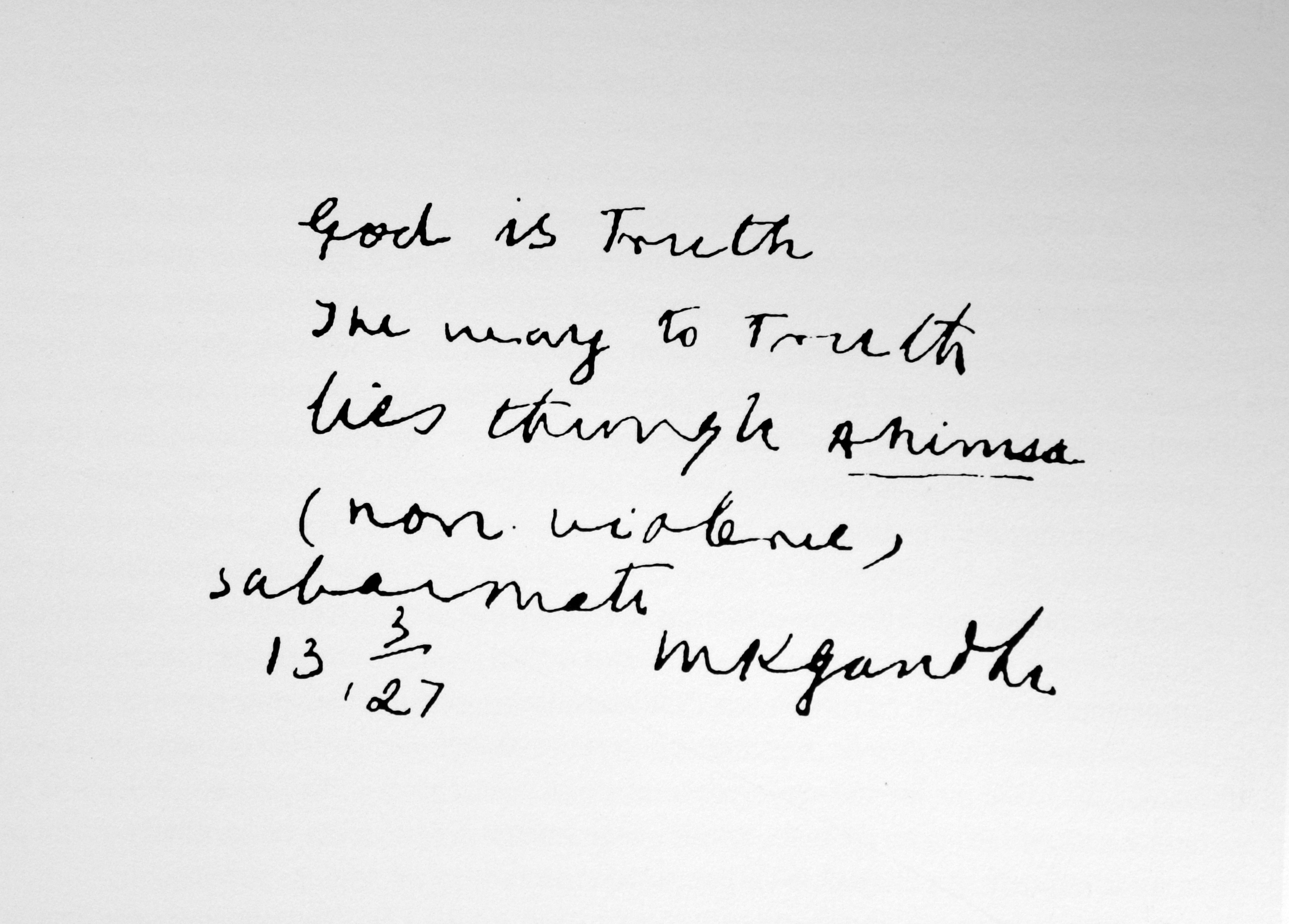

After being born in India, Gandhi spent much of his life in South Africa, practicing law and raising his family. Upon his return to India at the age of 45, Gandhi began immediately to “stir the pot”, as it were. The ethicist believed in non-violent revolt, was an anti-colonialist (India was then still under Britain’s rule), and a religious pluralist. At the age of 51 he was elected leader of the Indian National Congress, where he led nationwide campaigns to ease poverty, expand women’s rights, end India’s practice of “untouchability”, and praise self-rule (end colonialism). Starting at this time he began living life in extreme modesty – eating simple vegetarian meals, fasting for health, political and meditative purposes, and wearing a traditional Indian dhoti as a mark of respect to the lower classes. He spent his life helping others, helping himself, and helping his country. He was assassinated at the age of 78 for being “too accommodating” in his dealings with other nations (mainly Pakistan, at that time).

His birthday, October 2nd, is celebrated in India as a national holiday – the International Day of Nonviolence. Gandhi’s beliefs and opinions are ones that transcend time, if you’ll forgive our grand sentiments. Especially today, when violence sometimes seems to be one of our only constants, we could all take a page out of Gandhi’s book. Sleep, eat healthy, forgive, remain strong, listen, learn, and – most of all – love.

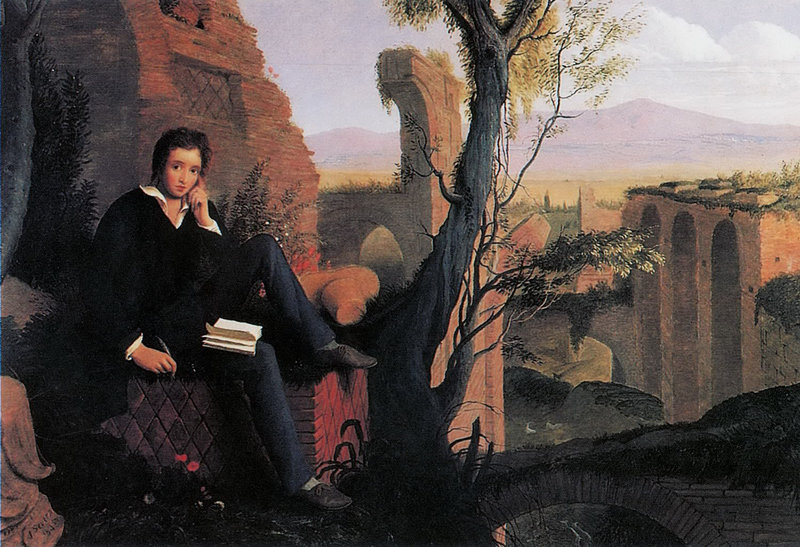

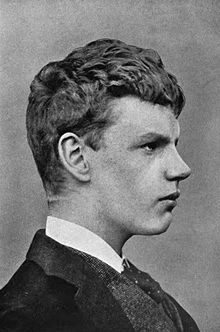

In the summer of 1816, Shelley befriended one of his first powerful and influential authors – Lord Byron. Percy and Mary spent a season with Byron in Switzerland – the summer ended up being one of the most important of Shelley’s life. Byron helped inspire the young radical, and Shelley wrote his romantic poem Hymn to Intellectual Beauty after an afternoon with Byron. It was during this summer, funnily enough, that Byron’s guests and friends were inspired to have a horror write-off. This writing competition of sorts was the inspiration behind Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Upon their return to England at the end of the year, it was discovered that Shelley’s wife, Harriet, had committed suicide. As unfortunate as the event was, it incited Shelley and Mary to finally marry. The two settled in a small hamlet in Buckinghamshire, where they befriended poets John Keats and Leigh Hunt – both of which would prove to be invaluable friends to Shelley in his last years. It was in these years that Shelley wrote and published a bulk of his most well-known works, including The Revolt of Islam and Prometheus Unbound, the latter of which is widely considered to be his most beloved epic work.

In the summer of 1816, Shelley befriended one of his first powerful and influential authors – Lord Byron. Percy and Mary spent a season with Byron in Switzerland – the summer ended up being one of the most important of Shelley’s life. Byron helped inspire the young radical, and Shelley wrote his romantic poem Hymn to Intellectual Beauty after an afternoon with Byron. It was during this summer, funnily enough, that Byron’s guests and friends were inspired to have a horror write-off. This writing competition of sorts was the inspiration behind Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Upon their return to England at the end of the year, it was discovered that Shelley’s wife, Harriet, had committed suicide. As unfortunate as the event was, it incited Shelley and Mary to finally marry. The two settled in a small hamlet in Buckinghamshire, where they befriended poets John Keats and Leigh Hunt – both of which would prove to be invaluable friends to Shelley in his last years. It was in these years that Shelley wrote and published a bulk of his most well-known works, including The Revolt of Islam and Prometheus Unbound, the latter of which is widely considered to be his most beloved epic work.

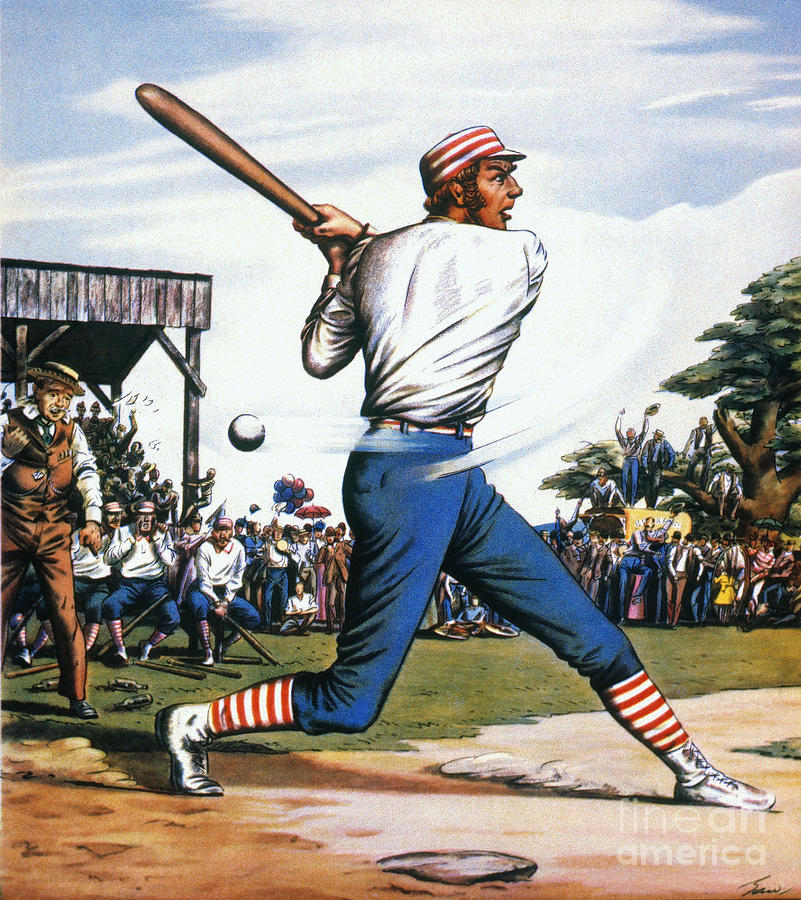

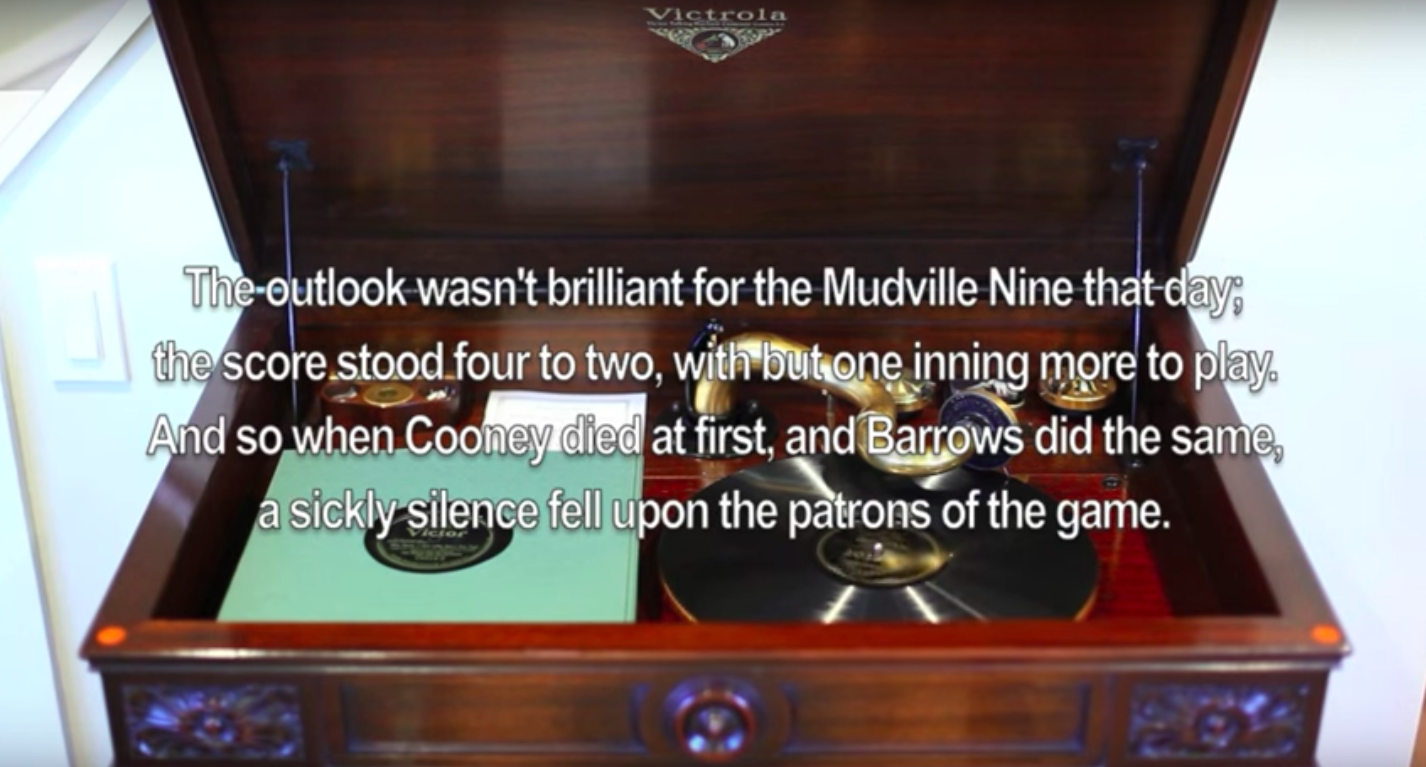

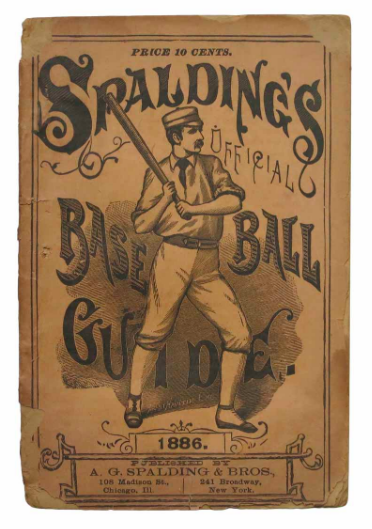

Ernest Thayer was a Harvard educated author, who began working at the age of 24 as a humor columnist for The San Francisco Examiner. On June 3rd, 1888, the elusive author “Phin” published a poem that would become a backbone of both American poetry and baseball. Thayer did not receive credit for the poem for several months (as he was not a boastful man), and when he finally did he was surprisingly close-lipped about it all. He never revealed whether he based the game or the character of Casey on a real player, though many have put forth possibilities.

Ernest Thayer was a Harvard educated author, who began working at the age of 24 as a humor columnist for The San Francisco Examiner. On June 3rd, 1888, the elusive author “Phin” published a poem that would become a backbone of both American poetry and baseball. Thayer did not receive credit for the poem for several months (as he was not a boastful man), and when he finally did he was surprisingly close-lipped about it all. He never revealed whether he based the game or the character of Casey on a real player, though many have put forth possibilities.

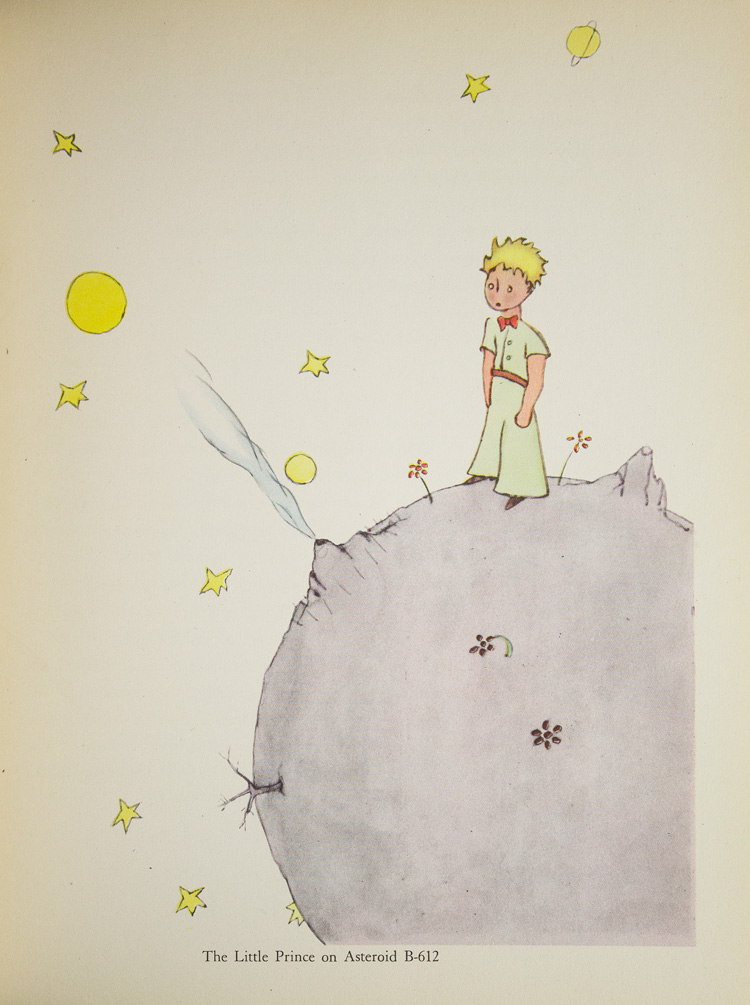

So said the Little Prince – an absolutely beloved character in the canon of Western Literature. Antoine de Saint-Exupéry wrote this story, a children’s story on the outside and a very adult study of human nature and morality on the inside. Saint-Exupéry, a French national, had fled Europe at the onset of World War II and wrote much of his tale during his 27 week stay in North America and Canada. Now normally we would do a blog on Saint-Exupéry’s life story and how he came to write such a popular and precious children’s tale, but today we are speaking of a specific day in this author’s life… the day he disappeared from the skies.

So said the Little Prince – an absolutely beloved character in the canon of Western Literature. Antoine de Saint-Exupéry wrote this story, a children’s story on the outside and a very adult study of human nature and morality on the inside. Saint-Exupéry, a French national, had fled Europe at the onset of World War II and wrote much of his tale during his 27 week stay in North America and Canada. Now normally we would do a blog on Saint-Exupéry’s life story and how he came to write such a popular and precious children’s tale, but today we are speaking of a specific day in this author’s life… the day he disappeared from the skies.

Unfortunately,

Unfortunately,

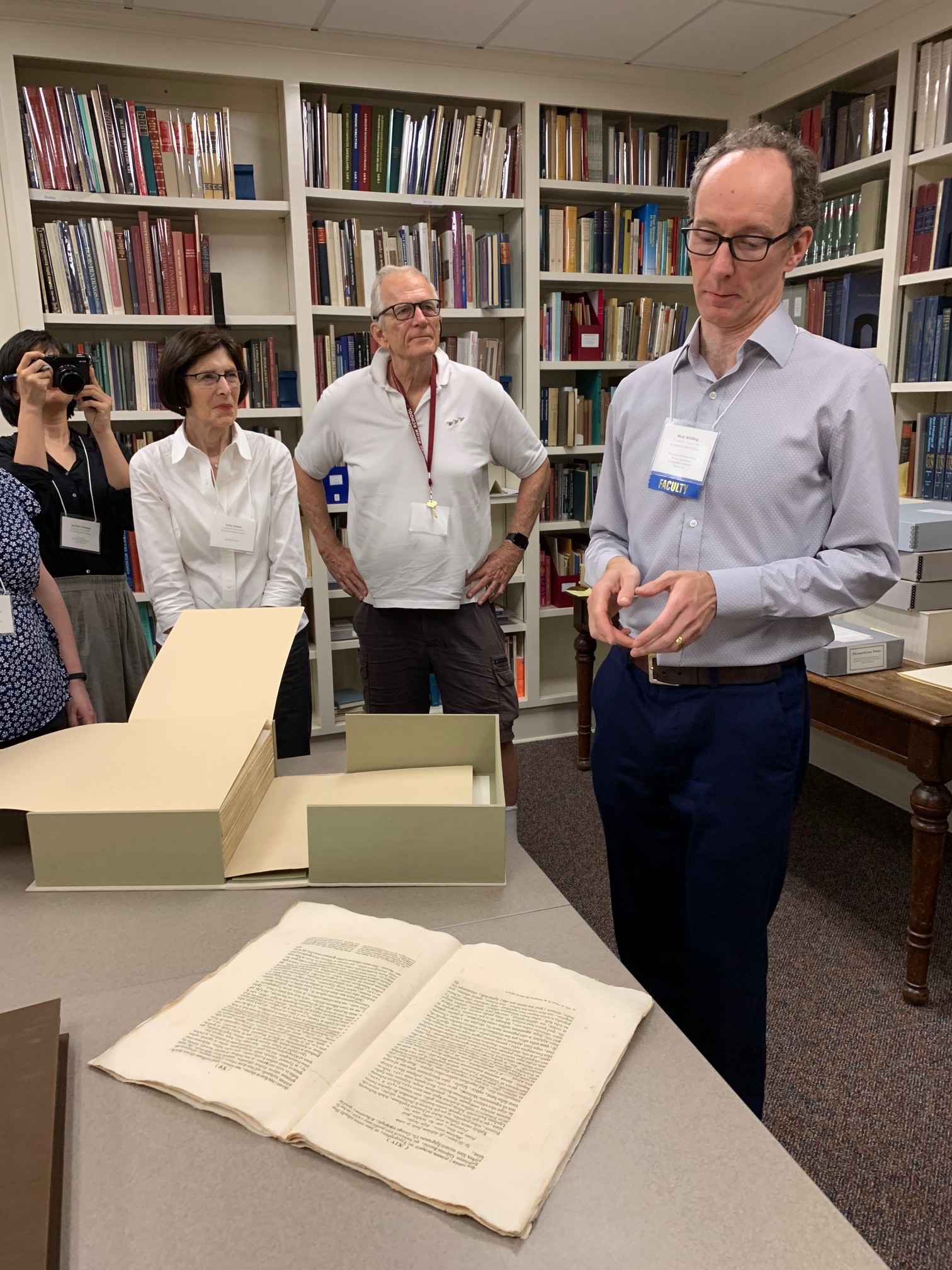

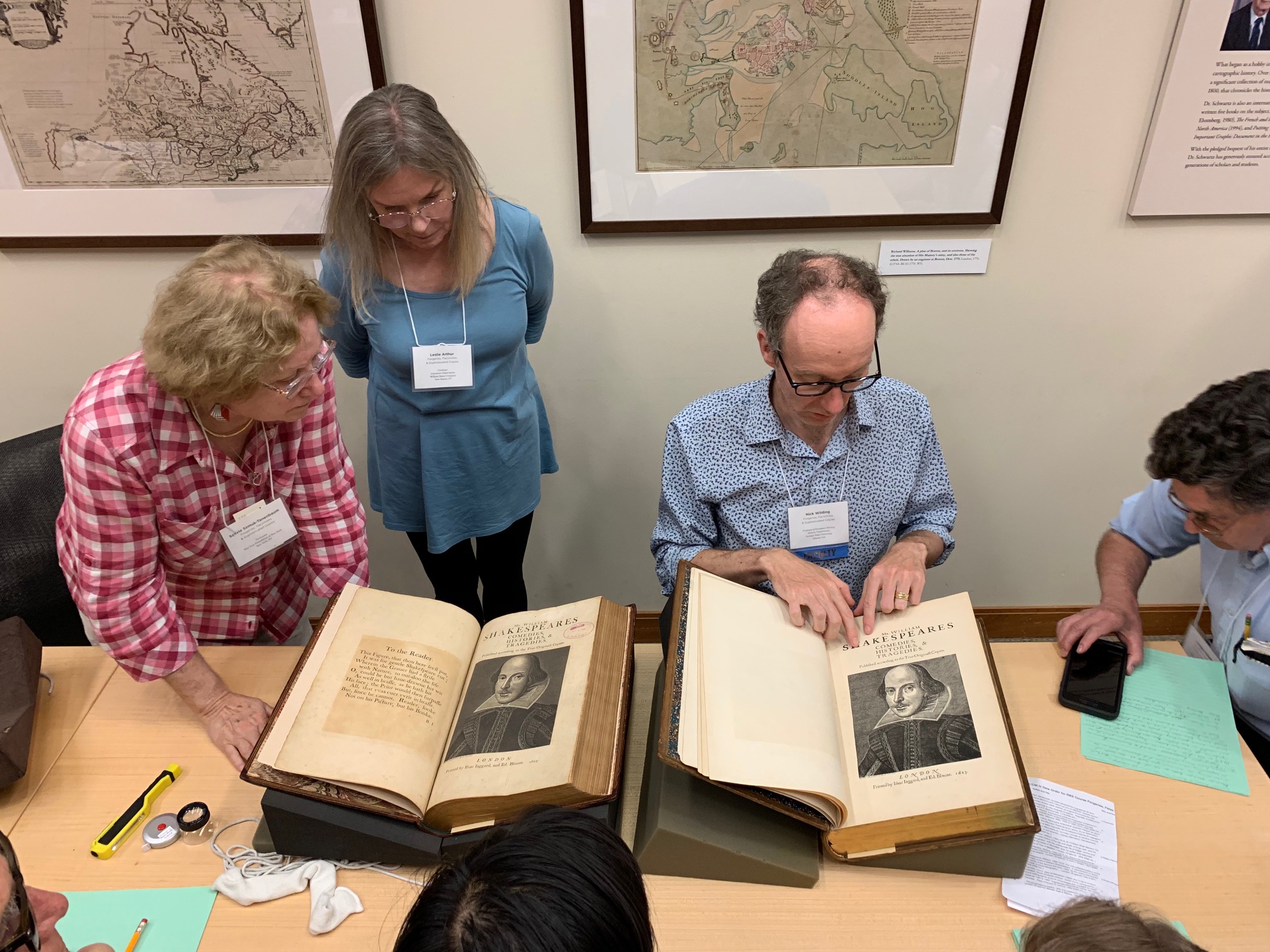

For those new to RBS, things kick off Sunday afternoon, 5ish. There’s a reception, a Michael Suarez welcome speech & restaurant night. The latter an opportunity for ~ 10 students to share a meal at one of the local ‘Corner’ restaurants, in my case, Lemongrass Thai. Wonderful food, wonderful company!

For those new to RBS, things kick off Sunday afternoon, 5ish. There’s a reception, a Michael Suarez welcome speech & restaurant night. The latter an opportunity for ~ 10 students to share a meal at one of the local ‘Corner’ restaurants, in my case, Lemongrass Thai. Wonderful food, wonderful company!

Eric Carle was born on June 25th, 1929 in Syracuse, New York, but his family originally being from Germany they moved back there and he was educated in art in Stuttgart. His father was drafted into the German army at the beginning of WWII, and eventually taken prisoner by Soviet Forces. Carle himself was also conscripted by the German government at the age of 15 to spend time with other boys his age building trenches on the Siegfried Line. Throughout all this time, Carle dreamed of returning to the United States, and finally, upon turning 23 he moved back to New York City with only $40 to his name. Carle was able to land a job as a graphic designer at

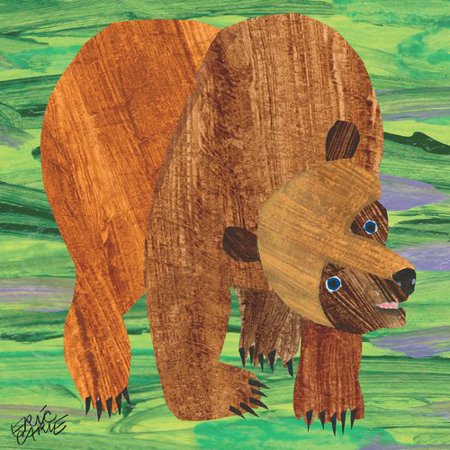

Eric Carle was born on June 25th, 1929 in Syracuse, New York, but his family originally being from Germany they moved back there and he was educated in art in Stuttgart. His father was drafted into the German army at the beginning of WWII, and eventually taken prisoner by Soviet Forces. Carle himself was also conscripted by the German government at the age of 15 to spend time with other boys his age building trenches on the Siegfried Line. Throughout all this time, Carle dreamed of returning to the United States, and finally, upon turning 23 he moved back to New York City with only $40 to his name. Carle was able to land a job as a graphic designer at  It was at this agency that author Bill Martin Jr. spotted a lobster Carle had drawn for an advert illustration and Martin decided to ask Carle to collaborate with him on a book for children – the result of which is one of Carle’s best known works… Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What Do You See? was published in 1967. The book was an immediate success for Martin (who authored the story) and Carle, and in relatively short time it became a best-seller. This popularity jump-started Carle’s career in books, and within just two years he was both writing and illustrating his own.

It was at this agency that author Bill Martin Jr. spotted a lobster Carle had drawn for an advert illustration and Martin decided to ask Carle to collaborate with him on a book for children – the result of which is one of Carle’s best known works… Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What Do You See? was published in 1967. The book was an immediate success for Martin (who authored the story) and Carle, and in relatively short time it became a best-seller. This popularity jump-started Carle’s career in books, and within just two years he was both writing and illustrating his own.

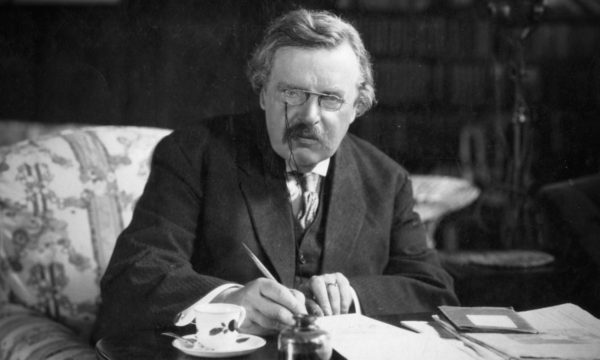

Gilbert Keith Chesterton was born on May 29th, 1874, in Kensington, London. His childhood is not elaborately researched, but we do know that he was born to a family of Unitarians, and as a young man was interested in the occult and regularly played (or practiced) with a Quija board with his younger brother (and only sibling) Cecil. He was educated at St. Paul’s School in London, but instead of continuing on to a university as you might have expected, Chesterton attended the Slade School of Art in London – in hopes of eventually becoming an illustrator. Though at Slade Chesterton took lessons in both art and literature, Chesterton left without a degree in either!

Gilbert Keith Chesterton was born on May 29th, 1874, in Kensington, London. His childhood is not elaborately researched, but we do know that he was born to a family of Unitarians, and as a young man was interested in the occult and regularly played (or practiced) with a Quija board with his younger brother (and only sibling) Cecil. He was educated at St. Paul’s School in London, but instead of continuing on to a university as you might have expected, Chesterton attended the Slade School of Art in London – in hopes of eventually becoming an illustrator. Though at Slade Chesterton took lessons in both art and literature, Chesterton left without a degree in either! When Chesterton was 27 years old, he married Frances Alice Blogg – an author herself, who would prove to be a major influence on Chesterton’s writing and religious life throughout the years. As www.chesterton.org mentions, Frances was in charge of all aspects of Chesterton’s life – kept his schedule for him, kept house, and kept him in check. According to the site, Chesterton often “had no idea where or when his next appointment was. He did much of his writing in train stations, since he usually missed the train he was supposed to catch. In one famous anecdote, he wired his wife, saying, ‘Am at Market Harborough. Where ought I to be?’” To which Mrs. Chesterton would almost inevitably respond with “Home.” The Chesterton’s were perhaps the epitome of the phrase “Behind every great man is an even greater woman.”

When Chesterton was 27 years old, he married Frances Alice Blogg – an author herself, who would prove to be a major influence on Chesterton’s writing and religious life throughout the years. As www.chesterton.org mentions, Frances was in charge of all aspects of Chesterton’s life – kept his schedule for him, kept house, and kept him in check. According to the site, Chesterton often “had no idea where or when his next appointment was. He did much of his writing in train stations, since he usually missed the train he was supposed to catch. In one famous anecdote, he wired his wife, saying, ‘Am at Market Harborough. Where ought I to be?’” To which Mrs. Chesterton would almost inevitably respond with “Home.” The Chesterton’s were perhaps the epitome of the phrase “Behind every great man is an even greater woman.”