By Kate Mitas

Before diving into the subject at hand, a brief, belated caveat:

Throughout this blog series, I have so far used “archive” to mean something at least vaguely equivalent to the Society of American Archivist’s definition: “[m]aterials created or received by a person, family, or organization, public or private, in the conduct of their affairs and preserved because of the enduring value contained in the information they contain or as evidence of the functions and responsibilities of their creator, especially those materials maintained using the principles of provenance, original order, and collective control; permanent records.” A recent discussion with Arthur Fournier (Fournier Fine & Rare), who was a panelist at the recent RBMS Conference session, “Defining the Archive” has prompted me to reexamine my use (or possibly, misuse) of the term. Arthur was kind enough to share his thoughts on the matter, which will be appearing in a future installment in the series, but, suffice it to say, my usage of “archive” in this blog is, at the very least, up for debate. For the sake of expediency, I’m going to keep using it as a broad term for the types of materials I’m referring to — most often, in my admittedly limited experience, collections of assorted original, printed and visual matter, often of a vernacular nature — and for now will just ask you to think critically about the term, how I’m using it, how you might define it otherwise, etc.

NB. Links to additional resources and full definitions of terms are embedded throughout this blog — please make use of them!

Right, now for the fun part: finally digging into your archive, interpreting your findings, and backing up your claims with reliable data. What could be easier?

Well, depending on your archive, quantum physics, for one, or perhaps learning to play “Mary Had a Little Lamb” on the piano with your toes. (Okay, I’m only speaking from experience in the latter example, but still.) Archives can be hard, and more than a little overwhelming on first approach, like having to assemble a complicated jigsaw puzzle that may or may not be complete and without knowing what the resultant picture should look like, in the full knowledge that your livelihood depends to some degree on your ability to not only piece the puzzle together but then also, and just as importantly, convince someone to buy it.

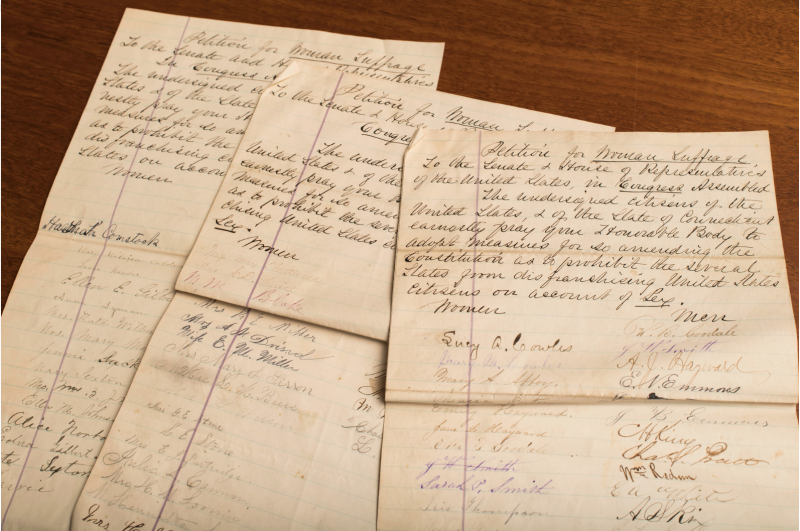

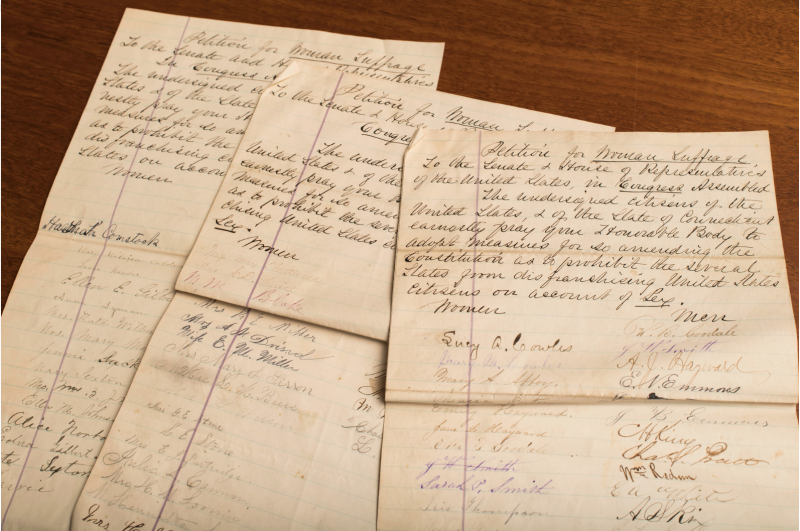

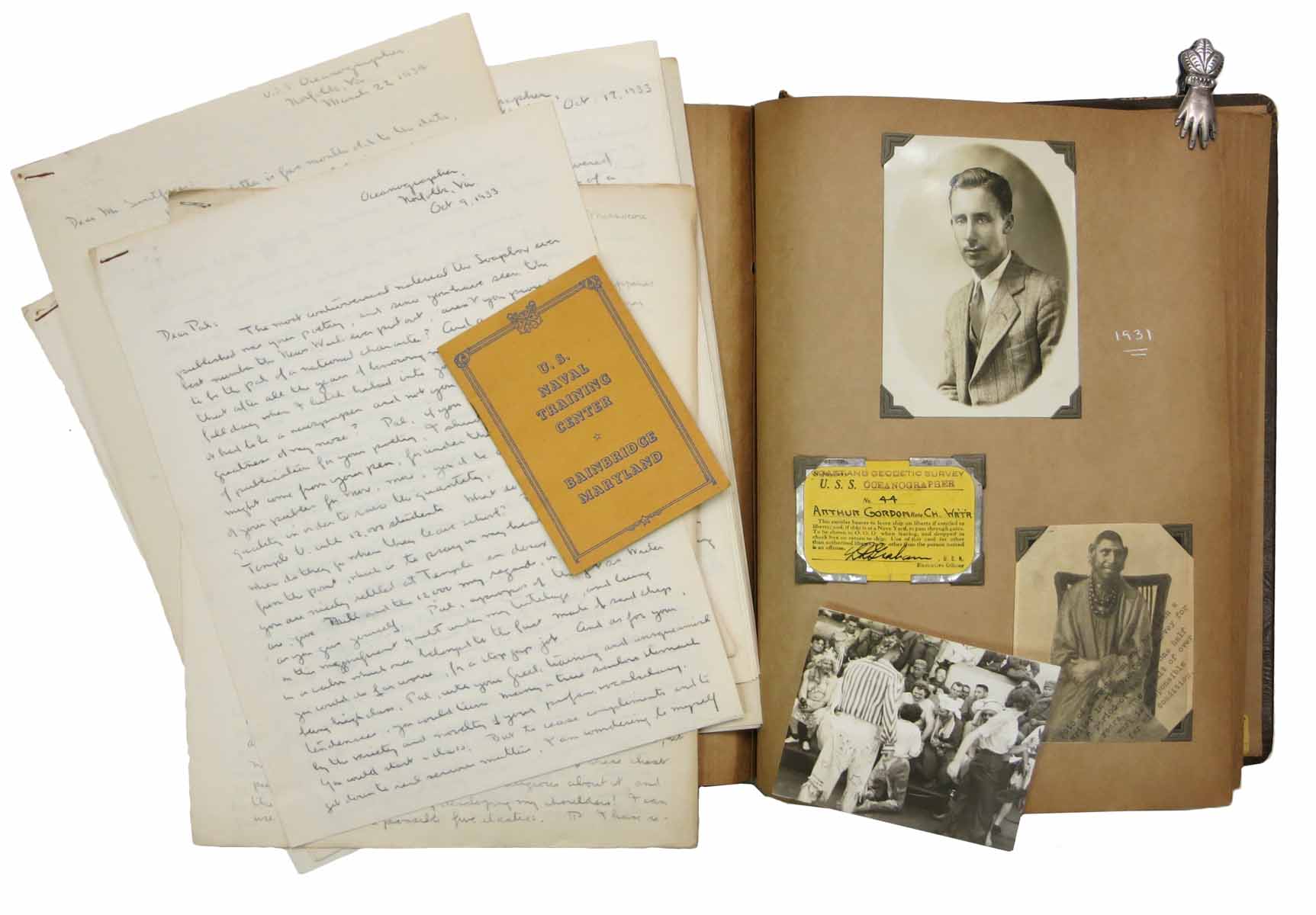

So, where to begin? Adrienne Horowitz Kitts (Austin Abbey Rare Books), a fellow CABS 2015 grad who recently made national headlines for her work on an archive of suffragist correspondence sent to Isabella Beecher Hooker, including letters from Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, advises beginners not to be intimidated. “Take a day, or two or three to get to know the contents; look at each piece and dust it off, get an idea of what is in there. A combination of items in the archive — letters, manuscripts, pamphlets, leaflets, photographs — together tell the story.”

A portion of the suffragist archive. Photo courtesy of J. Adam Fenster/University of Rochester.

Archivists have a term for this: artifactual literacy, “the ability to understand, contextualize and interpret primary sources.” So, in a way, do booksellers: selling point. Finding the story and telling it is not only the hardest and most rewarding aspect of cataloguing an archive, it’s also the best way I know of to convince someone to buy it.

Understanding How Institutions View Archives

It’s worth pointing out here that booksellers and institutions value archives differently. Commercial value isn’t synonymous with research value: institutions add to their collections for a variety of reasons (and with sometimes vastly different budgets at their disposal), and “research value” is far from being a monolithic criterion. Knowing some of the basic lenses institutions apply can not only help you understand what makes your archive important, it can also help you decide which institutions to approach, and even why an institution may decide against purchase.

Very broadly speaking, an archive might be considered useful to an institution on the basis of its intrinsic value, its evidential value, or its informational value. In extremely simplified terms, what this means is that an archive might be valued on the basis of what it is, what it reveals about the work and activities of its creator(s), or what it tells us about the time and place of its creation.

Adrienne’s suffragist correspondence seems to me a pretty clear example of an archive with a high degree of intrinsic value: the content is hugely significant, of course, but I doubt similar letters exchanged between minor figures in the movement would have garnered the same kind of national attention. Not surprisingly, the University of Rochester, who purchased the material, holds both the John and Isabella Beecher Hooker papers and the papers of Susan B. Anthony. Conversely, if a similar suffragist archive didn’t include any correspondence from major figures, but nevertheless revealed organizational details like meeting minutes, procedural issues, locations of talks/protests, etc., it might be considered useful on the basis of its evidential value; the archive of a previously unknown but active suffragist might be said to have informational value.

The point of all of this isn’t that you have to learn archival theory to catalogue archives, it’s that, whether you’re aware of it or not, these broad angles of emphasis — what an archive is in and of itself, what it reveals about its creator’s activities, and what information it provides— are in fact already influencing how you interpret and describe the intellectual content of an archive. Telling any story requires deciding which details are important and which to leave out, and the story of your archive is no different.

Determining Intellectual Content

Unless you know everything there is to know about the material you’re working with — and I suspect it’s a rare occasion indeed when that happens, if it happens at all — understanding and researching your archive inevitably go hand in hand. So how do you go about figuring out just what exactly you have, especially if you have no idea what to look for in the first place, and might not recognize an important detail if you were staring directly at it?

It’s likely that every bookseller has a unique approach to this conundrum: some slightly mystical application of personal experience, knowledge, curiosity, technological skill, etc., that somehow lands them at the tail end of cataloguing an archive feeling like they’ve found its most compelling and honest narrative. I’ve found that I can usually augment my lack of experience and knowledge with an ability to parse data for relevant information quickly and deduce potential avenues of inquiry from it — so my research often involves rapid-fire Google searches, followed by digging around on primary source sites like ancestry.com and newspapers.com. That’s not necessarily the best way to go about it, however. Garrett Scott (Garrett Scott, Bookseller), offers these useful, and moderately analog, observations, instead:

I tend . . . to have a blank sheet of paper and two sharp pencils (they have to be sharp!) as the tangible browser cache on my desk. Ideally I try to pick at whatever loose bits of fact need figuring out and follow my curiosity and by the time a diary or archive or collection is cataloged I have usually used only a portion of the info I’ve scribbled on the blank sheet and have wasted time going down a few unrelated alleys. (From dental surgery I once ended up combing theater ads for child prodigy performers in Philadelphia in the 1850s — there was some connection but not much — and I regret it not one bit.)

I figure it’s like the recent claim that humans didn’t see the color blue until they had the language for it — I don’t see interesting things about archives (or future buys) until I’ve created my own language and interest in it that comes about from noodling around with references and following where the material and curiosity (related and unrelated) leads.

The key thing to remember, no matter how you approach it, is to let the material dictate the narrative, which means keeping an open mind about where you might wind up, focusing on the contents of the material itself (i.e., if the creator of your archive turns out to be the first cousin twice removed of a famous 19th century explorer, but the contents of your archive document a widow’s life in Philadelphia during the Civil War, you won’t be doing yourself any favors hyping the tangential connection to exploration — and in fact, might be eliding the very thing your archive was meant to preserve), and supporting your findings. It’s incredibly easy to make assumptions about your material, and even to get excited about it based on those assumptions. Nevertheless, to my mind, we have a responsibility both to our customers and to our profession to represent what we sell as honestly as we can.

The ethical ramifications of imposing a narrative might seem a bit muffled on the supplier’s side of the archival equation, but the consequences can be far-reaching for booksellers as well as researchers, and not only because booksellers can lose customers from the practice. Imposing a narrative can help perpetuate stereotypes and biases, which in turn restricts avenues of cultural inquiry and the commerce that depends on it.

As Elizabeth Birmingham recounts in her essay on architect Marion Mahony Griffin, “‘I See Dead People’: Archive, Crypt, and an Argument for the Researcher’s Sixth Sense,” imposed narratives and accepted narratives are sometimes (often? usually?) interchangeable. In Birmingham’s case, this meant that over the course of more than a decade of research, and in spite of having access to Mahony Griffin’s own manuscript account of her work and marriage to architect Walter Burley Griffin and nearly 700 accompanying illustrations, Birmingham went along with the prevailing narrative that Mahony Griffin was merely her husband’s helper, and a grudging one at that. Eventually, however, Marion Mahony (as she is now more commonly known) became recognized as one of the great architects of the 20th century, and gained prominence for her artistic ability as well — most of the drawings of Frank Lloyd Wright’s designs in his major 1910 Wasmuth portfolio were done by Mahony, and a book of her botanical paintings was published in 2005. Birmingham is now one of her strongest champions, and a copy of Mahony’s manuscript archive has been digitized and is available in full to any who wish to view it. “The researcher’s sixth sense isn’t the ability to see the dead but our potential to help the dead, who do not know they are dead, finish their stories,” Birmingham ruefully concludes in her essay, “and we do this in the moment we realize their stories are ours” (Landmark Essays on Archival Research, p. 169).

Research Methods

Good archival research, particularly for our relatively limited ends, often comes down to a combination of information literacy — the ability to recognize when you need to use sources, identify credible sources, and use them efficiently and appropriately — and the same sense of professionalism and self-discipline (dare I say “honor”?) that any good bookseller applies to bibliographic research. Just as you wouldn’t skip collating a book or checking a reference number even if you’ve gotten the book from one of the best dealers in the business, you shouldn’t skip doing some basic, but necessary, research on your archive to ensure that it is, in fact, what you say it is.

Recognizing when to use sources:

For me, recognizing when to use sources is pretty simple: I don’t know something, and I think it might be important to the story whose trail I’m sniffing out. I ask myself questions the entire time I’m working my way through an archive, testing each new bit of information against what I think I know about the material. Who is this person? What event are they referring to? Why does this matter to them? Could it matter for another reason? What do they mean when they say x, and is it the same thing I mean when I say it? How does this compare to other archives like this that I’ve seen? Etc., etc., etc. Questioning myself is a way of honing my interpretation as I go, and forcing myself to support that interpretation (or discredit it) with research from outside sources when necessary.

Evaluating the credibility of sources:

Since I mentioned journalism in an earlier blog, it seems appropriate to turn to that profession for advice in identifying and evaluating credible sources.* Drawing on both the Harvard Kennedy School’s Journalist’s Resource and Columbia College’s online guidelines, here are some good questions to ask about your source:

- Where was it published?

- How long ago was it published?

- Who wrote it, and what are their credentials? Might they have a conflict of interest/implicit or explicit bias (e.g., be a relative of your subject, an enthusiast rather than a scholar, etc.)?

- Who is the intended audience?

- Are the conclusions drawn supported by evidence?

- Is it a primary or secondary source? If primary, are you able to view an image (at least) of the original document, or just a transcript?

Sometimes less-than-credible sources, like Wikipedia, whose information can and will be frequently altered, are nevertheless handy for pointing the way to credible sources — I’ve found a number of good resources by following the links in an entry’s “References” and “External Links” sections, and have used these as a way to confirm the veracity of a Wikipedia entry, too. Conversely, seemingly credible sources, like those found on Ancestry, are not always as reliable as you might think: family trees are usually compiled by family members and are rarely correct, and the Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software used to translate primary source documents into the searchable terms on the site can be exceptionally bad. It is always, always better to look at the original document yourself, if possible.

*And, just for good measure, here’s a link to the Society for Professional Journalism’s (SPJ) Code of Ethics, too: http://www.spj.org/ethicscode.asp.

Using Sources:

Much as booksellers often bemoan the inroads digitization has made on the trade, the research benefits of internet archives are hard to dispute. The ease with which I can view high-resolution scans of California’s earliest newspapers on the California Digital Newspaper Collection (CDNC) or pull up the passenger record of a 19th-century immigrant to Philadelphia on Ancestry.com would’ve been unfathomable to booksellers a generation ago. These sites have their limitations, of course, both in the lack of availability of certain material and the prevalence of errors impeding search results. Nevertheless, the package deal of Ancestry and Newspapers.com has been the single best archival research tool to which we’ve subscribed, and is well worth the annual fee.

Archivist and CABS 2015 grad Caitlin Moriarity also suggests ArchiveGrid — which allows users to search archive collections across institutions through Worldcat — and encourages booksellers to reach out to archivists for research help, too. “Half of my day is spent answering reference questions that have been emailed to the library, and we are happy to look into finding more information than what is in the catalog record or finding aid. It is one of the best parts of my job!”

Google

Probably the single most frequently used research tool we all turn to is, of course, Google: the information age’s very own omniscient narrator, Delphic Oracle and global Magic 8 Ball rolled into one. Google can be extraordinarily informative, extraordinarily misleading and extraordinarily useless. Like any tool, you have to know how to use it.

Google’s search algorithm is a notoriously well-kept secret, changing 500 – 600 times a year and relying on over 200 unique signifiers to calculate the results of your latest search for, say, cute cat videos. I’m not going to pretend to know what these signifiers are: suffice it to say, mind-boggling calculations occur every time you perform a Google search.

Luckily, there are ways to limit your search results. Here is a partial list of Google search operators that I’ve found to be useful:

“ “ Exact phrase search

+ Adds a word to the search

– Subtracts a word from the search

OR Searches for one search term or another

allintitle: Searches for an entire group of words in the site’s title

allintext: Searches for an entire group of words in the body of a site’s text

* Missing word search

There are many, many more search operators and methods of searching. For more information, as well as examples and explanations, check out MIT’s Google Search Tips or Moz’s blog, “Mastering Google Search Operators in 67 Easy Steps.”

Alternatively, Google Advanced Search offers a guided search tool, with fields designated for the most common search operators.

Keep in mind that word order matters. Front-loading your searches with the terms you’re looking for yields different results than, say, asking a full question (e.g., “Steamship San Francisco wreck causes” versus “How did the steamship San Francisco wreck?”). Another tip, suggested by Jason Rovito (Jason Rovito, Bookseller), is to have a specific browser devoted exclusively to research, and not clear the browser cache. Google relies on your search history to help determine the relevancy of your search results. As Jason relates, “One of the more fascinating discoveries when I was helping to reconstruct a library of a then-obscure/completely forgotten book collector is that as I searched Google for various items in his library (or went off on tangential searches—e.g. searching up the names on bookplates), the relevancy of my future searches dramatically increased. It was a weird sort of conjuring act / following in someone’s (partial) footsteps. So that, eventually, when I re-Googled the name of the collector (albeit in fairly detailed, drilled-down searches), his name finally started appearing.”

Potentially, of course, overly refined search results may exclude information you don’t know you’re looking for, which might be problematic. One especially important thing to watch that you don’t fall prey to, as well, are “featured snippets”: those boxes of answers that appear at the top of your search results. They aren’t topping your list because they’re the best answer, but because they’re top-ranked. Anticipatory features like this on Google have come under attack lately for helping to promote fake news and hate organizations. Just remember that these results are based on site popularity, not relevancy (and certainly not accuracy).

Knowing When to Stop

In reality,most archives don’t require the kind of months of research that you may now be imagining they need. If you’re not careful, you can very easily over-research an archive, and it’s important to know when the value of your time outweighs the value added by further research. In my experience, archives may not require much more than for me to establish basic details, like where and when a person lived, or to glean a rough overview on an unfamiliar topic. Those that do require a considerable amount of research may be more profitable if they’re flipped to a more knowledgeable bookseller — at the very least, the time you’ll need to catalogue a research-heavy archive has to be factored into its cost. In fact, you can even use an estimate of the time it would take to catalogue an archive to work with your customer’s budget constraints. As John Kuenzig (Kuenzig Books) points out, “Many customers have more money in their acquisitions budget than their cataloging budget. So it can be useful to talk with potential buyers about what level of cataloging would be necessary to ensure success — I’ve even quoted two prices with different levels of cataloging.”

Ideally, archives should require just enough research for us to sell them. Knowing where that line falls is a skill that develops with experience, but is an essential skill for anyone dealing in archives. (Whether we stick to that line or choose to indulge our curiosity is another matter.)

Next in the series: Telling the Story

Johanna Maria Lind was born in 1820 into a rather unusual household for the times. Technically illegitimate, she was born to a bookkeeper and a school teacher who were not yet married. Though her mother had already divorced her first husband for adultery (understandable but definitely not the norm in the early 1800s), she would not marry Lind until after her first husband passed away, for religious reasons.

Johanna Maria Lind was born in 1820 into a rather unusual household for the times. Technically illegitimate, she was born to a bookkeeper and a school teacher who were not yet married. Though her mother had already divorced her first husband for adultery (understandable but definitely not the norm in the early 1800s), she would not marry Lind until after her first husband passed away, for religious reasons. In 1843 Lind was in the midst of a tour in Europe and while in Denmark met author Hans Christian Andersen, who fell madly in love with her. Though Lind did not reciprocate his feelings, the two became friends and Andersen is said to have written several fairy tales inspired by her! One can only assume that the later “The Nightingale” was one of these few. A year later, Lind began performing in Germany and Austria, where she connected with musicians Robert Schumann, Hector Berlioz and Felix Mendelssohn (who, though married, also fell madly in love with her and then died prematurely 4 months later, leaving Lind shattered) who were all inspired by her great talent. Mendelssohn even wrote a part for her in an opera debuted after his death, where she took the proceeds and donated them for a musical scholarship in Mendelssohn’s name. It is around this time that Lind became known as the “Swedish Nightingale.” She was madly popular in both musical and non-musical communities, as she donated much of her earnings to charities of her choosing – and would continue to do so for decades.

In 1843 Lind was in the midst of a tour in Europe and while in Denmark met author Hans Christian Andersen, who fell madly in love with her. Though Lind did not reciprocate his feelings, the two became friends and Andersen is said to have written several fairy tales inspired by her! One can only assume that the later “The Nightingale” was one of these few. A year later, Lind began performing in Germany and Austria, where she connected with musicians Robert Schumann, Hector Berlioz and Felix Mendelssohn (who, though married, also fell madly in love with her and then died prematurely 4 months later, leaving Lind shattered) who were all inspired by her great talent. Mendelssohn even wrote a part for her in an opera debuted after his death, where she took the proceeds and donated them for a musical scholarship in Mendelssohn’s name. It is around this time that Lind became known as the “Swedish Nightingale.” She was madly popular in both musical and non-musical communities, as she donated much of her earnings to charities of her choosing – and would continue to do so for decades. In 1849, P.T. Barnum (as in the circus) approached Lind to begin a tour of the United States. Lind agreed, and due to Barnum’s intense publicity of her coming arrived in the United States already famous. Her performances were so anticipated that her concert tickets were being sold at auction for triple their worth! Throughout the year she spent touring America under Barnum’s management, Lind made roughly $350k. Today, that equates to almost $10 million. Guess what Lind did with the money? You probably guessed correctly – she donated most of it to American and European charities! After a year under Barnum’s thumb Lind broke their contract to manage herself – somewhat tired of the intense publicity of her performances. During this time her pianist, Julius Benedict, left and went back to Europe, and Lind hired German pianist and composer Otto Goldschmidt to take his place. The two were married in less than a year in Boston at the end of their tour.

In 1849, P.T. Barnum (as in the circus) approached Lind to begin a tour of the United States. Lind agreed, and due to Barnum’s intense publicity of her coming arrived in the United States already famous. Her performances were so anticipated that her concert tickets were being sold at auction for triple their worth! Throughout the year she spent touring America under Barnum’s management, Lind made roughly $350k. Today, that equates to almost $10 million. Guess what Lind did with the money? You probably guessed correctly – she donated most of it to American and European charities! After a year under Barnum’s thumb Lind broke their contract to manage herself – somewhat tired of the intense publicity of her performances. During this time her pianist, Julius Benedict, left and went back to Europe, and Lind hired German pianist and composer Otto Goldschmidt to take his place. The two were married in less than a year in Boston at the end of their tour.

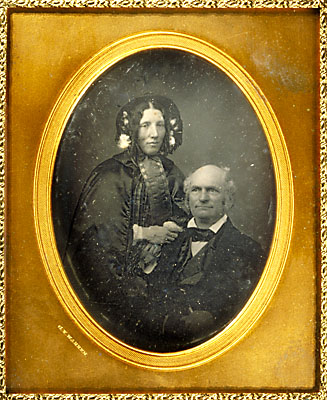

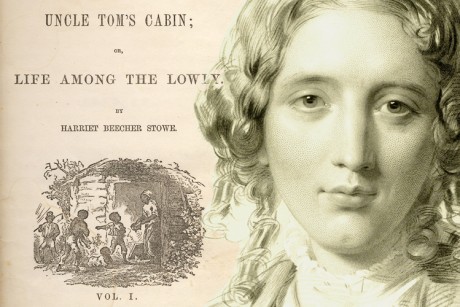

Living once more with her father but now at an older age, Harriet was better able to both understand her father’s views and choose when to agree and disagree with him. From the time of the 1836 pro-slavery riots in Cincinnati, Lyman Beecher took a strong stance against the act of slavery. Clearly his thoughts echoed in Harriet (as well as all of his other children), and as a young woman Harriet found friends in abolitionist circles and literary clubs in Cincinnati. It was in one of these literary clubs, the Semi-Colon Club, that Beecher met seminary teacher Calvin Ellis Stowe. The two were married and shortly thereafter moved to a small house in Brunswick, Maine. Stowe shared Harriet’s strong beliefs in many aspects of life, and no topic more so than the concept of slavery. The two would help house several slaves escaping north to Canada on the Underground Railroad throughout the 1840s and 50s.

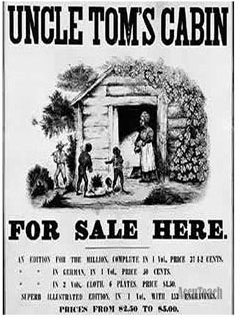

Living once more with her father but now at an older age, Harriet was better able to both understand her father’s views and choose when to agree and disagree with him. From the time of the 1836 pro-slavery riots in Cincinnati, Lyman Beecher took a strong stance against the act of slavery. Clearly his thoughts echoed in Harriet (as well as all of his other children), and as a young woman Harriet found friends in abolitionist circles and literary clubs in Cincinnati. It was in one of these literary clubs, the Semi-Colon Club, that Beecher met seminary teacher Calvin Ellis Stowe. The two were married and shortly thereafter moved to a small house in Brunswick, Maine. Stowe shared Harriet’s strong beliefs in many aspects of life, and no topic more so than the concept of slavery. The two would help house several slaves escaping north to Canada on the Underground Railroad throughout the 1840s and 50s.  Over a decade after their marriage in 1850, Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act, stating that all slaves that had escaped were legally able to be hunted down and returned to their masters. Stowe was so disgusted with the way slavery was being handled that she decided to begin a work of literature representing her views on the unfair and disgraceful act of slavery. Basing her lead character after the famously escaped and inspiring ex-slave Josiah Henson, Stowe completed the first draft of Uncle Tom’s Cabin in less than a year. Almost immediately after publication, Stowe’s “emotional portrayal of the impact of slavery, particularly on families and children” became a best-seller.

Over a decade after their marriage in 1850, Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act, stating that all slaves that had escaped were legally able to be hunted down and returned to their masters. Stowe was so disgusted with the way slavery was being handled that she decided to begin a work of literature representing her views on the unfair and disgraceful act of slavery. Basing her lead character after the famously escaped and inspiring ex-slave Josiah Henson, Stowe completed the first draft of Uncle Tom’s Cabin in less than a year. Almost immediately after publication, Stowe’s “emotional portrayal of the impact of slavery, particularly on families and children” became a best-seller.  Throughout her life, Stowe published articles supporting political causes, abolition, then African American rights and women’s rights all leading the pack. Shortly after the end of the Civil War the Stowe family (Harriet and her husband Calvin and their 7 children) purchased land in Northern Florida and would winter there far from the chilly and difficult New England weathers for the next 15 years, until Calvin’s health prevented them from long-distance traveling. They chose Florida because one of Stowe’s many brothers became a minister and teacher for the emancipated slaves in the south and helped them become educated and find paid work. Abolition, emancipation and the plight of the African Americans in the United States was never far from Stowe’s heart, and she championed for their rights until her death in 1896 at the age of 85. Her grave in Andover, Massachusetts reads “Her Children Rise up and Call Her Blessed.”

Throughout her life, Stowe published articles supporting political causes, abolition, then African American rights and women’s rights all leading the pack. Shortly after the end of the Civil War the Stowe family (Harriet and her husband Calvin and their 7 children) purchased land in Northern Florida and would winter there far from the chilly and difficult New England weathers for the next 15 years, until Calvin’s health prevented them from long-distance traveling. They chose Florida because one of Stowe’s many brothers became a minister and teacher for the emancipated slaves in the south and helped them become educated and find paid work. Abolition, emancipation and the plight of the African Americans in the United States was never far from Stowe’s heart, and she championed for their rights until her death in 1896 at the age of 85. Her grave in Andover, Massachusetts reads “Her Children Rise up and Call Her Blessed.”

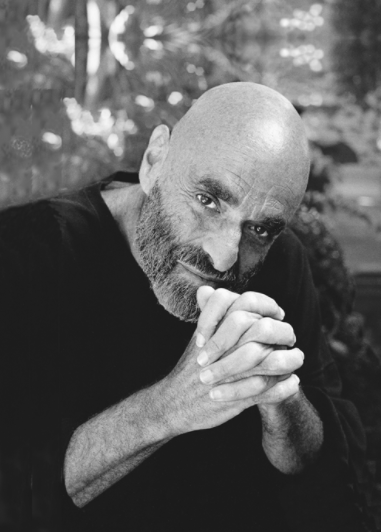

Shel (short for Sheldon) Silverstein was born on September 25th, 1930 in Chicago, Illinois. He spent all of his formative years in Illinois, attending Roosevelt High School and then the University of Illinois. Though unfortunately expelled from the University, he was then able to enroll in the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts. Now, bear with me readers, as there are some contradictory articles to be found online and truthfully I can’t tell whether he was then enlisted in the army or drafted, but either way he fought in Japan and Korea sometime around 1948-1951. When he returned from the army, Silverstein spent a bit of time in college at Roosevelt University, though would later be quoted as saying his years in college were a bit of a waste. He is quoted as saying, “Imagine – four years you could have spent traveling around Europe meeting people, or going to the Far East of Africa or India, meeting people, exchanging ideas, reading all you wanted to anyway, and instead I wasted it at Roosevelt.” That being said, however, it was also when he was first published (in the Roosevelt Torch, a student newspaper)! His time at the Chicago College of Performing Arts (part of Roosevelt University) was spent studying music and composition, a talent he would pursue throughout his life.

Shel (short for Sheldon) Silverstein was born on September 25th, 1930 in Chicago, Illinois. He spent all of his formative years in Illinois, attending Roosevelt High School and then the University of Illinois. Though unfortunately expelled from the University, he was then able to enroll in the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts. Now, bear with me readers, as there are some contradictory articles to be found online and truthfully I can’t tell whether he was then enlisted in the army or drafted, but either way he fought in Japan and Korea sometime around 1948-1951. When he returned from the army, Silverstein spent a bit of time in college at Roosevelt University, though would later be quoted as saying his years in college were a bit of a waste. He is quoted as saying, “Imagine – four years you could have spent traveling around Europe meeting people, or going to the Far East of Africa or India, meeting people, exchanging ideas, reading all you wanted to anyway, and instead I wasted it at Roosevelt.” That being said, however, it was also when he was first published (in the Roosevelt Torch, a student newspaper)! His time at the Chicago College of Performing Arts (part of Roosevelt University) was spent studying music and composition, a talent he would pursue throughout his life. Beginning in the 1960s while being published in Playboy, Silverstein began working on poems and cartoons for children. His book The Giving Tree was first published (after four years of trying to find someone willing to publish it) in 1964, and some would argue is his most classic work – having sold over 5 million copies and still amazingly popular. For the next three decades Silverstein would release many best sellers and award winning titles to the delight of children and adults alike. His children’s poems are known for their simplicity and brevity, but also for their tremendous sense of humor! All are accompanied by an intricate black and white cartoon, drawn, of course, by Silverstein himself. However, comics were not his only claim to fame – throughout his life Silverstein kept up a solid musical career as well. While working at Playboy in 1959, Silverstein recorded his first album called Hairy Jazz. It wouldn’t stop there, however, as Silverstein would go on to create over a dozen music albums over the course of his lifetime. Though one could argue that his music was not quite as popular as his comics and poetry, it is obvious that his level of creativity knew no bounds!

Beginning in the 1960s while being published in Playboy, Silverstein began working on poems and cartoons for children. His book The Giving Tree was first published (after four years of trying to find someone willing to publish it) in 1964, and some would argue is his most classic work – having sold over 5 million copies and still amazingly popular. For the next three decades Silverstein would release many best sellers and award winning titles to the delight of children and adults alike. His children’s poems are known for their simplicity and brevity, but also for their tremendous sense of humor! All are accompanied by an intricate black and white cartoon, drawn, of course, by Silverstein himself. However, comics were not his only claim to fame – throughout his life Silverstein kept up a solid musical career as well. While working at Playboy in 1959, Silverstein recorded his first album called Hairy Jazz. It wouldn’t stop there, however, as Silverstein would go on to create over a dozen music albums over the course of his lifetime. Though one could argue that his music was not quite as popular as his comics and poetry, it is obvious that his level of creativity knew no bounds!