In honor of Miguel de Cervantes’ (assumed) birthday, we wanted to dig a little deeper into this masterpiece of Western literature, to find out why it carries the weight it does in the book world. How can such an early work (the first part having been published in only 1605!) be considered the first modern novel? How can one work be considered social satire, comedy, tragedy and social and ethical commentary all at one time? Let’s find out!

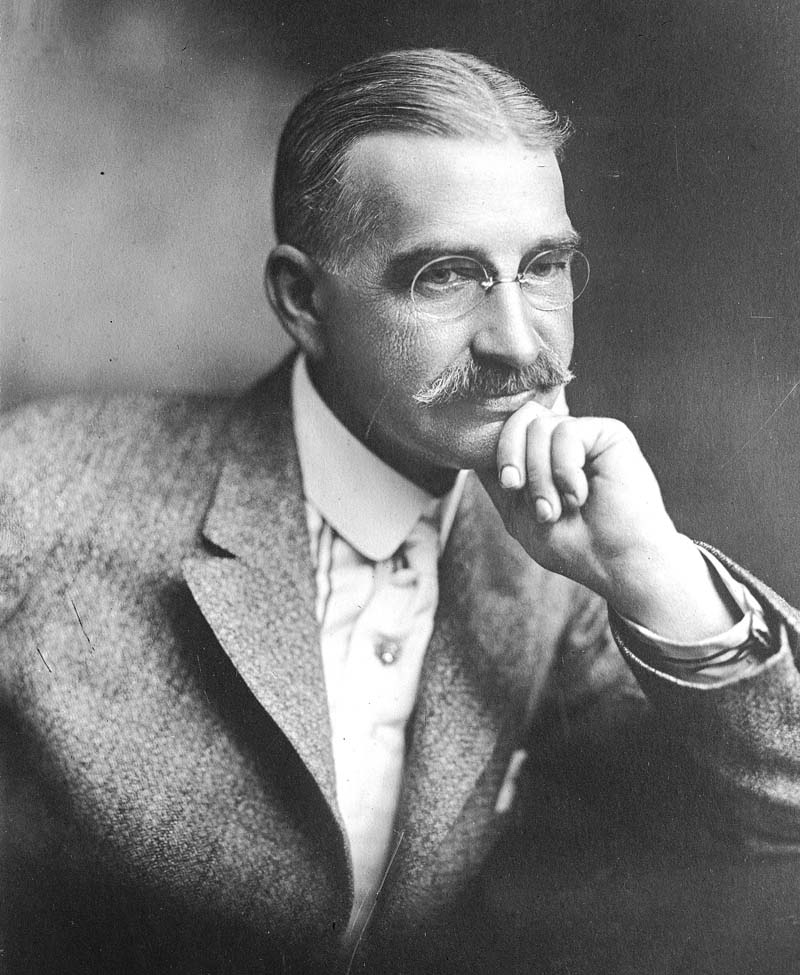

Fairly little is known about Miguel de Cervantes. Remember, he lived at roughly the same time as Shakespeare (who, surprise surprise… we also know fairly little about). We know that he was the second of 7 children, with a father constantly in debt and a mother confident and literate enough to support herself and all of her children while the father was imprisoned for debt from 1553 to 1554. Miguel obviously learned a few things from his mother, as he worked a myriad of jobs as a young man (including being arrested for dueling, having a military commission, being an intelligence agent and as a tax collector) and though he was never an extremely wealthy man, he was not often out of work!

Throughout this time, Cervantes published a few plays and some poems, none of any great significance, and none that provided a living for the man and his family. By 1605, Cervantes hadn’t been “properly” published in almost 20 years! Nevertheless, he began writing a work he considered a satire – he challenged a “form of literature that had been a favourite for more than a century, explicitly stating his purpose was to undermine ‘vain and empty’ chivalric romances. He wrote about the common man. He used everyday lingo, normal conversation rather than epic speeches – it was considered a great success. Though there was a great amount of time between the two parts of the work, its popularity did not wane. The first part is considered the more popular of the two, with its comedic characterizations and its hilarity, while the second part is considered more introspective and critical, with greater characterization of the individuals in the story.

Throughout this time, Cervantes published a few plays and some poems, none of any great significance, and none that provided a living for the man and his family. By 1605, Cervantes hadn’t been “properly” published in almost 20 years! Nevertheless, he began writing a work he considered a satire – he challenged a “form of literature that had been a favourite for more than a century, explicitly stating his purpose was to undermine ‘vain and empty’ chivalric romances. He wrote about the common man. He used everyday lingo, normal conversation rather than epic speeches – it was considered a great success. Though there was a great amount of time between the two parts of the work, its popularity did not wane. The first part is considered the more popular of the two, with its comedic characterizations and its hilarity, while the second part is considered more introspective and critical, with greater characterization of the individuals in the story.

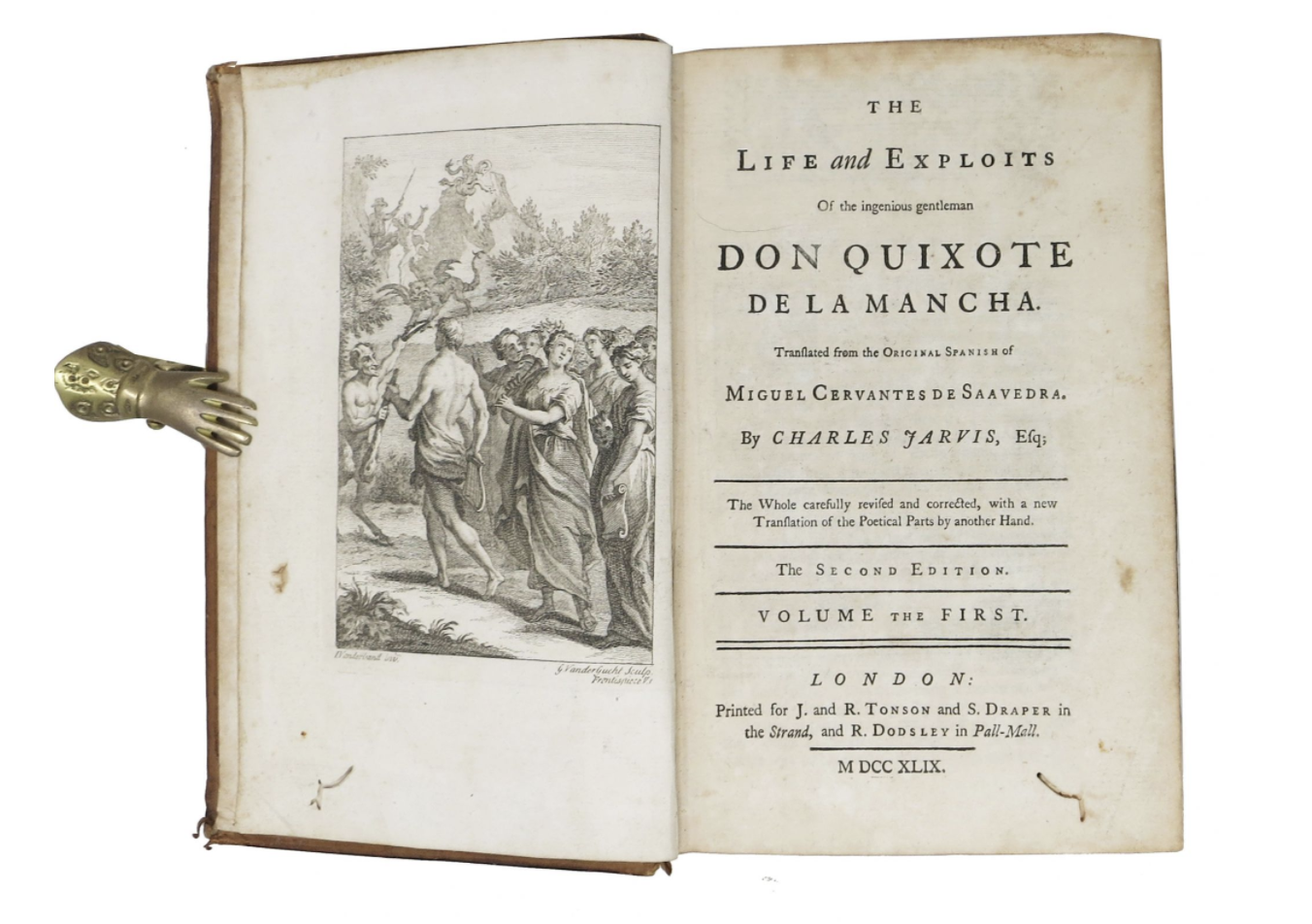

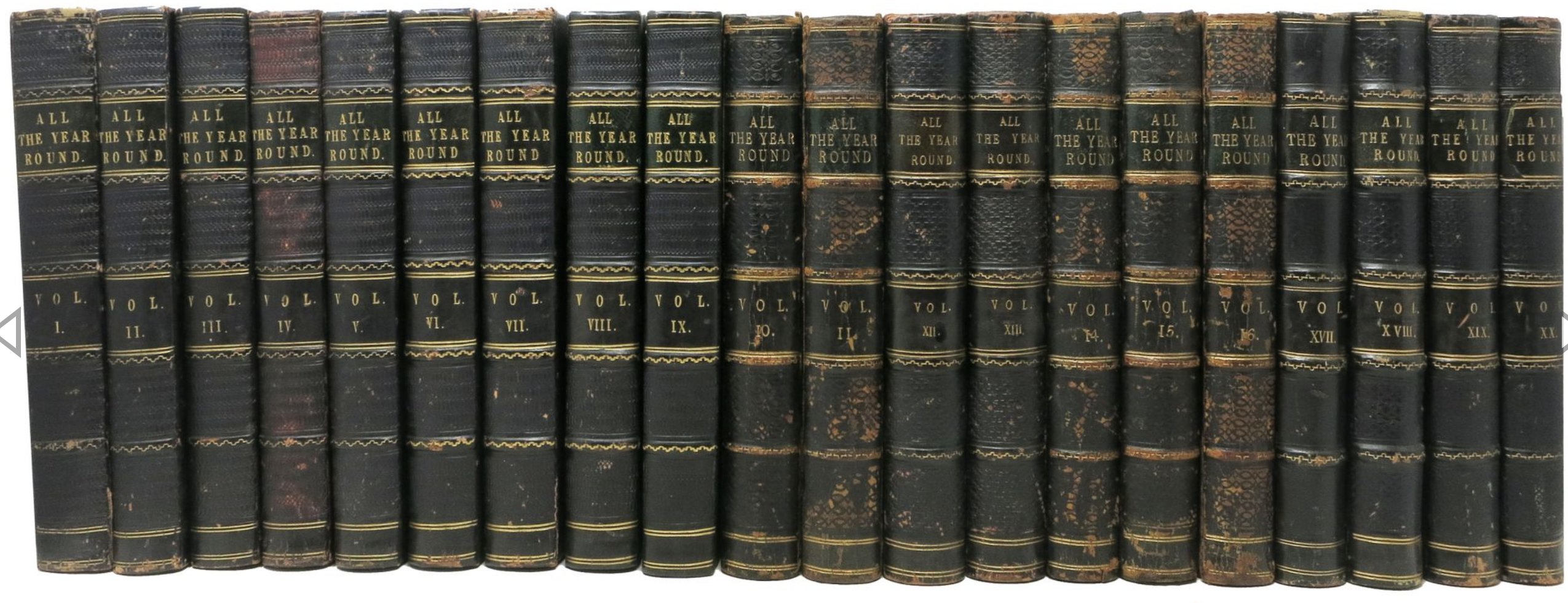

There are differing opinions on the Don Quixote of the time – it held popularity with the masses, and garnered financial success for Cervantes, but was considered a financial failure in the long haul… we aren’t sure how that works but are willing to trust the experts! The great interest in the work came during a resurgence in popularity during the mid 18th century, when literary editor John Bowle argued that “Cervantes was as significant as any of the Greek and Roman authors then popular”, and proceeded to publish an annotated edition of the work in 1781. Ever since, Don Quixote has been considered a staple of modern literature. Why, you may ask?

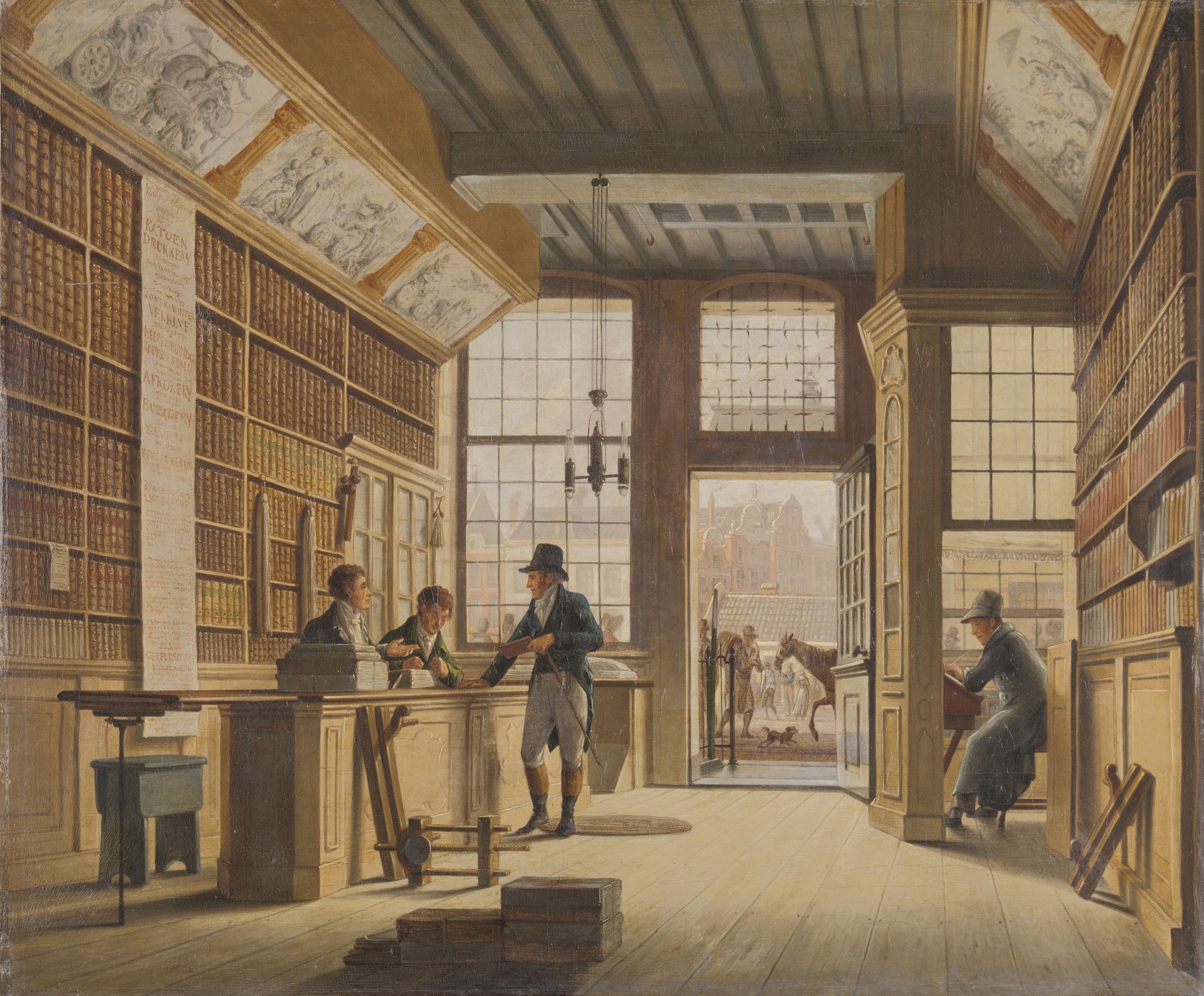

Our London 1749 holding of Don Quixote, published into the English by Charles Jarvis and only the 2nd edition of its kind!

Author Edith Grossman published a new English translation of the novel in 2003 and noted how the novel straddles both comedy and tragedy in the same moments… “when I first started reading the Quixote I thought it was the most tragic book in the world, and I would read it and weep… As I grew older… my skin grew thicker… and so when I was working on the translation I was actually sitting at my computer and laughing out loud. This is done as Cervantes did it… by never letting the reader rest. You are never certain that you truly got it. Because as soon as you think you understand something, Cervantes introduces something that contradicts your premise.” And thus is the beauty and genius of the novel… Part I introduces enough comedic elements to amuse and hold your interest in the characterization, with Part II garnering strength and empathy for the characters you’ve come to love, feeling their pains and their moments of humility. Truly a work ahead of its time, today we honor Miguel de Cervantes and his inimitable hero Don Quixote (and the loyal and true Sancho Panza, of course). Happy Birthday (maybe) to Miguel de Cervantes!

***

***

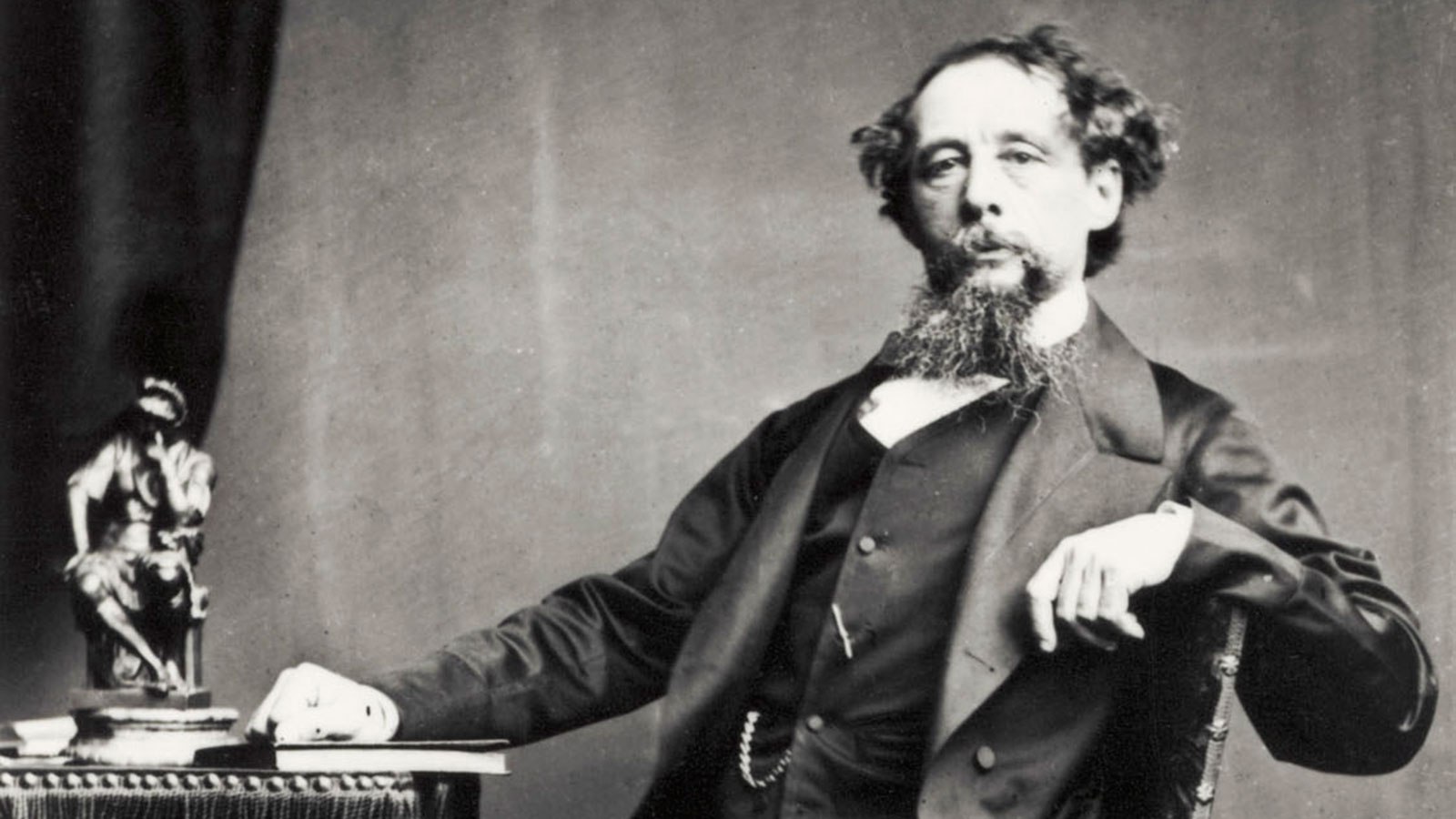

Starting with a short overview of the story (for the .000001% of you that have been living under a rock these past 160 years), we can come to look at the “expectations” housed within and see what we can decipher from the moral tale it holds. When young orphan Pip encounters an escaped criminal hiding in a churchyard one Christmas Eve, it gives him the fright of his life. The young boy is scared into thieving for the convict, and though the criminal is recaptured and clears Pip of suspicion, the incident colors Pip’s outlook on life. The young boy is sent to the house of the spinster and slightly mad Miss Havisham, to be used as entertainment for the lady and her adopted, aloof and haughty daughter Estella. Pip falls in love with Estella and visits them regularly until he is old enough to be taught a trade as an apprentice blacksmith. Four years into Pip’s apprenticeship, however, a lawyer arrives with news that Pip has anonymously been provided with enough money to become a gentleman. An astonished Pip heads to London to begin his new life, assuming Miss Havisham is to thank for his unexpected new windfall. Once in London the young Pip is introduced into some society, and makes new friends. His heart still belonging to Estella, he is ashamed of his previous life and expects his social advancement, new wealth and sudden social standing to sway her emotions towards him more favorably. It does not, Estella remains cold as ever, and Pip’s illusions are finally shattered when he realizes that his benefactor is not Miss Havisham at all, but the escaped convict Magwitch whom he helped in the churchyard all those years before. Through many mishaps and misfortunes, Pip and his friends attempt to help Magwitch escape England (which is ultimately unsuccessful), where he had returned to simply to make himself known to Pip. Pip learns valuable lessons throughout the story – interestingly not necessarily from those with money and social standing, but more often than not from those in his own class. The story has a kind ending, with Pip and an altered, warmer Estella walking hand in hand over a decade after her initial rejection of him (though Dickens originally planned a more likely, yet more disheartening end to the story and was convinced by Edward Bulwer-Lytton to change it).

Starting with a short overview of the story (for the .000001% of you that have been living under a rock these past 160 years), we can come to look at the “expectations” housed within and see what we can decipher from the moral tale it holds. When young orphan Pip encounters an escaped criminal hiding in a churchyard one Christmas Eve, it gives him the fright of his life. The young boy is scared into thieving for the convict, and though the criminal is recaptured and clears Pip of suspicion, the incident colors Pip’s outlook on life. The young boy is sent to the house of the spinster and slightly mad Miss Havisham, to be used as entertainment for the lady and her adopted, aloof and haughty daughter Estella. Pip falls in love with Estella and visits them regularly until he is old enough to be taught a trade as an apprentice blacksmith. Four years into Pip’s apprenticeship, however, a lawyer arrives with news that Pip has anonymously been provided with enough money to become a gentleman. An astonished Pip heads to London to begin his new life, assuming Miss Havisham is to thank for his unexpected new windfall. Once in London the young Pip is introduced into some society, and makes new friends. His heart still belonging to Estella, he is ashamed of his previous life and expects his social advancement, new wealth and sudden social standing to sway her emotions towards him more favorably. It does not, Estella remains cold as ever, and Pip’s illusions are finally shattered when he realizes that his benefactor is not Miss Havisham at all, but the escaped convict Magwitch whom he helped in the churchyard all those years before. Through many mishaps and misfortunes, Pip and his friends attempt to help Magwitch escape England (which is ultimately unsuccessful), where he had returned to simply to make himself known to Pip. Pip learns valuable lessons throughout the story – interestingly not necessarily from those with money and social standing, but more often than not from those in his own class. The story has a kind ending, with Pip and an altered, warmer Estella walking hand in hand over a decade after her initial rejection of him (though Dickens originally planned a more likely, yet more disheartening end to the story and was convinced by Edward Bulwer-Lytton to change it).

Before Dickens published A Christmas Carol (written in only a six short weeks, and published the week before Christmas at considerable expense to Mr. Dickens), he and his wife Catherine were experiencing your average hardships. They were expecting their fifth child, and supplications of money from his aging father and family, with dwindling sales from his previous works had put him into a tough financial place. In the fall of 1843, a 31-year-old Dickens was asked to deliver a speech in Manchester, supporting adult education for manufacturing workers there. His extreme interest in the subject (one that hit a bit too close to home, I believe) and his resolve to aid the lowly pushed an idea to the forefront of his mind – a speech can only do so much… to get to the crux of the matter he would need to get into the hearts, minds and homes of his readership and country. As the idea for A Christmas Carol took shape and his writings began, Dickens himself became utterly obsessed with his own story. As his friend John Forster remarked, Dickens

Before Dickens published A Christmas Carol (written in only a six short weeks, and published the week before Christmas at considerable expense to Mr. Dickens), he and his wife Catherine were experiencing your average hardships. They were expecting their fifth child, and supplications of money from his aging father and family, with dwindling sales from his previous works had put him into a tough financial place. In the fall of 1843, a 31-year-old Dickens was asked to deliver a speech in Manchester, supporting adult education for manufacturing workers there. His extreme interest in the subject (one that hit a bit too close to home, I believe) and his resolve to aid the lowly pushed an idea to the forefront of his mind – a speech can only do so much… to get to the crux of the matter he would need to get into the hearts, minds and homes of his readership and country. As the idea for A Christmas Carol took shape and his writings began, Dickens himself became utterly obsessed with his own story. As his friend John Forster remarked, Dickens