No one reading a Dickens novel can deny the author’s enthusiasm for the theatrical. To see a young orphan used and abused by adults at every turn, to have to bear a young girl dying and her desolate grandfather withering away by her grave, or a miser being shown the error of his ways by ghosts… Dickens captured the hearts and attention of readers all over the world, and was, quite arguably, the most popular writer throughout the Victorian period. However, Dickens “the author” was not merely that – he was a man of many talents, much of which sat in the dramatic arts. A known producer of amateur theatrics, an actor himself, and performer until the day he died – Dickens captivated the world and unfortunately paid the ultimate price for living for his audiences.

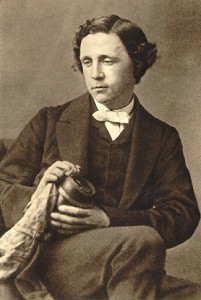

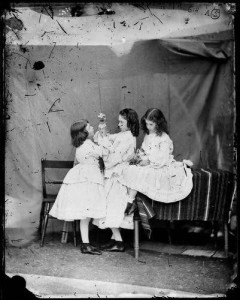

A youthful Dickens.

Dickens as a Young Performer

Charles John Huffam Dickens was born in Portsmouth, England in 1812 into what started out as an idyllic childhood that soon turned into a slightly unstable family situation. Because of his father’s debts, the author was forced to leave school at the age of 12 to work in a blacking warehouse where he earned six shillings a week pasting labels on pots of boot blacking. This formative time in Dickens’ childhood gave inspiration to many of the traumas portrayed in his works – most notably Dombey & Son and Old Curiosity Shop. Later on in life, Dickens would live with a fear of his literary talent failing him, and the constant looming possibility of ruin and poverty. One could argue that these fears, when present in the most popular celebrity of Victorian England, stemmed from this early age and his abbreviated childhood, as he was called upon at an early age to contribute to the family earnings.

Dickens grew up with a love of performing, and in 1832 at the age of 20 Dickens gave serious thought to becoming an actor. He went so far as to arrange an audition for himself at the Lyceum Theatre through the help of the then-current stage manager. Unfortunately (for Dickens, rather than for us), he came down with a severe cold the day of the audition and was unable to attend. Dickens continued with a steadfast love of theater and attended as often as he could.

Dickens’ Theatricals and The Frozen Deep

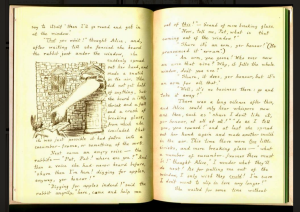

Once Dickens achieved great success with his writings (beginning with Pickwick Papers and Oliver Twist and only becoming more intense and thrilling as installments of his novels went on), his almost super-human energy (the author reportedly walked about 12 miles every day) allowed him to humor his theatrical side and stage amateur performances with the help of family and friends. In 1852, after the author and his family moved to Tavistock House in London, Dickens converted the schoolroom into a miniature theater, “capable of holding an audience of ninety” (Fitzsimmons, The Charles Dickens Show p. 26). He and his children, along with their friends, put on performances every few weeks, and Dickens excelled in as many aspects of the theater as he did in literature. His longtime friendship with Wilkie Collins was often a great inspiration in these times, and Collins even wrote some plays specially to be performed by the Dickens household.

Engraving of the end scene in “The Frozen Deep”, Dickens as the wild Wardour lying on the frozen ground. (Illustrated London News, 17th Jan. 1857).

One of the last amateur performances Dickens was to participate in was The Frozen Deep, a tragic theatrical written by Collins (with the significant editing and assistance of Dickens) in which Dickens played the role of Richard Wardour, as well as stage manager. Not only would this production prove to be significant in the way of theater (its success warranted a performance in front of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert), but it also was the momentous occasion that brought Dickens together with his later love, Ellen Ternan. Ellen, an 18-year-old young actress that was hired by Dickens, along with her mother and older sister Maria to play in The Frozen Deep, would soon become the scandal that the public blamed for the dissolution of Charles’ marriage to his wife, Catherine Hogarth.

Though the home theatricals soon dissipated, as Dickens bought the country home “Gad’s Hill Place” in Kent and, though very much frowned upon, separated from his wife, Dickens was soon to begin the next phase in his thespian career with a series of Reading Tours that he would continue until a few months before his death.

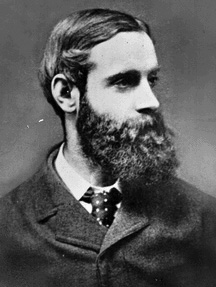

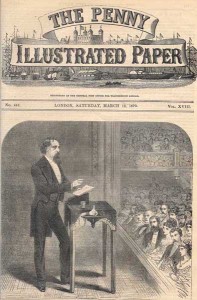

Dickens and his custom-made podium, specially designed by himself so as not to cut his body language off from his audience.

A One Man Show

“For the readings were an entertainment. They were not readings in the literal sense of the word. Dickens was a magnificent actor, with a wonderful talent for mimicry. He seemed able to alter not only his voice, his features and his carriage but also his stature. He disappeared and the audience saw, as the case might be, Fagin, Scrooge, Pickwick, Mrs. Gamp… or a host of others. Character after character appeared on the platform, living and breathing in the flesh” (Fitzsimmons p. 15). Dickens began reading professionally at a time when some say his literary powers were beginning to decline. Though he got some serious negative feedback from a few close friends about the idea (his longtime friend John Forster, for one, told Dickens that it was demeaning for an author to perform his own work), Dickens persisted. After reading in Edinburgh to an audience of over 2000, Dickens explained his euphoria at performing his work to Forster in a letter, “I must do something, or I shall wear my heart away. I can see no better thing to do that is half so hopeful in itself, or half so well suited to my restless state.” Fitzsimmons attributes much of Dickens’ wish to read (and possibly rightfully so) to its use as an outlet for his restlessness and miserable situation at home, and to the idea that he could make use of his theatrical talents and desire to be a thespian, all the while earning money to assuage his fear of living in poverty.

Dickens’ readings, however, exacted a great emotional strain on the author, and were obviously a direct contributor to his much too early demise. He performed many “shows” in a very small period of time, and the constant traveling, worry and keeping up of a charming & animated façade took its toll. However, Dickens refused to relent and disappoint his audiences. Reportedly, while giving a reading in Baltimore on his birthday in February of 1868, the distinguished statesman Charles Sumner came to visit the author at his hotel at 5 in the afternoon, and found Dickens in a right state, “covered in mustard poultices and apparently voiceless” (Fawcett, Dickens the Dramatist p. 171). At Sumner’s protestations against the author performing that evening, Dickens’ traveling manager George Dolby stated that, though he had told the author that it was ill-advised to perform that evening, Dickens would take the stage despite his ill health. In the words of Dolby to the statesman, “You have no idea how he will change when he gets to that little table.”

It was during this intense scheduled period of readings that Dickens was involved in the Staplehurst rail crash, an incident that left the author in even poorer health from the strain on his nerves and his subsequent mistrust of the rail system. Directly after the accident, Dickens helped tend to the wounded and dying, and got back on the train to rescue his unfinished manuscript of Our Mutual Friend. Little known to the public, Ellen Ternan and her mother were traveling with Dickens from Paris when the accident happened, and Dickens was able to avoid an appearance at the inquest in order to save Ternan the scandal such a fact would immediately produce.

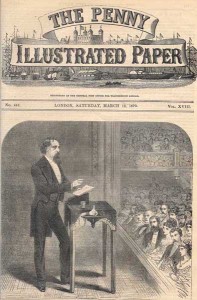

The front page of The Penny Illustrated Paper, dated March 19th, 1870 – just four days after Dickens’ final public reading.

One of the continued strains on the author, with regard to his reading performances, was his portrayal of Nancy’s murder by Bill Sikes, taken from Oliver Twist. The absolute terror and melodrama of the scene took a great toll on Dickens, so much so that Dolby wrote, “That the frequency with which he persisted in giving this Reading was affecting him seriously, nobody could judge better than myself, living and travelling with him as I was.” Disregarding this constant strain on his nerves and his extreme bouts of depression and illness, Dickens persisted. If anything, this obsession with portraying the murder scene with voice as well as action just perfectly for his audiences shows the energetic state of his mind, despite a failing body and spirit.

Ignoring his declining health and personal turmoil, Dickens continued to read publicly until just three months before he suffered a fatal stroke, with his last public reading given on 15 March 1870. Dickens was to conduct reading tours for over a decade – and not any single performance to less than a full house. There is no doubt in our minds that should this literary icon have chosen the stage rather than the pen, he would have found similar great success and admiration for his work.

Dickens the Renaissance Man

Dickens will always be remembered for his literary genius – the man who created universal and beloved characters and stories, the man who became the face of English literature. Additionally, Dickens should also be remembered for his all-around charm and allure, for his ability to captivate audiences with more than just words, but with his entire being.

Tavistock Books maintains a specialty in the works of Charles Dickens – first editions of his work, Dickens in parts, his plays, his biographical works, and even letters, pictures, and items related to the author and his life. Hence the name of our shop after the London home Dickens turned into an amateur theater for his friends and family. Look out next week for our monthly list of “Select Acquisitions”, also titled “Theatrically Speaking” – a list of crossovers between literature and the performing arts. Email Margueritte at msp@tavbooks.com to be added to our Mailing List!

Click here to see our Dickens items in shop –>

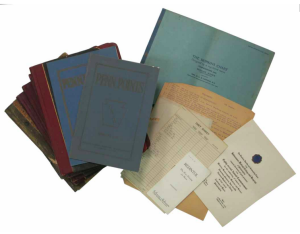

This set of 5 Nursing Student journals were written between 1923 and 1926 by one Mildred Godwin, a class of ’26 nursing student at Crozer Hospital, Chester, Pennsylvania. Within these journals the young lady records diverse class notes beginning in September of 1923 from lectures by her professors – Dr. Crowther, Miss Burkhard, Dr. Gray, etc. The subject of her entries range widely across the medical spectrum, from items such as Social Service to “Why Cases are Referred.” A very interesting archive of post WWI nursing education! Check it out here>

This set of 5 Nursing Student journals were written between 1923 and 1926 by one Mildred Godwin, a class of ’26 nursing student at Crozer Hospital, Chester, Pennsylvania. Within these journals the young lady records diverse class notes beginning in September of 1923 from lectures by her professors – Dr. Crowther, Miss Burkhard, Dr. Gray, etc. The subject of her entries range widely across the medical spectrum, from items such as Social Service to “Why Cases are Referred.” A very interesting archive of post WWI nursing education! Check it out here> This is no ordinary promotional photograph album or scrapbook… at least, not in terms of subject! The Alaska Blue Fox Company seem to have produced this interesting documentary album, providing an invaluable historical look at a very successful fox farming venture (yes, you read that correctly. No, there’s nothing I can do about it) on Bushy Island, in the Southeast Alaska Islands. After WWI there was a rise in fur prices, giving some eccentric entrepreneurs an opportunity to lease the island in the Tongass National Forest off the coast of Alaska and stock it with some 20 breeding pairs of foxes – all for your wearing pleasure. Be unnerved here>

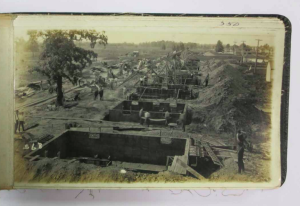

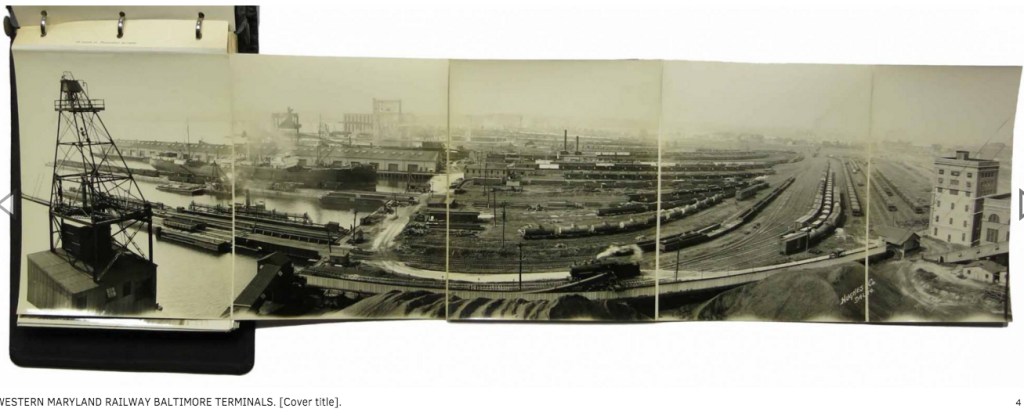

This is no ordinary promotional photograph album or scrapbook… at least, not in terms of subject! The Alaska Blue Fox Company seem to have produced this interesting documentary album, providing an invaluable historical look at a very successful fox farming venture (yes, you read that correctly. No, there’s nothing I can do about it) on Bushy Island, in the Southeast Alaska Islands. After WWI there was a rise in fur prices, giving some eccentric entrepreneurs an opportunity to lease the island in the Tongass National Forest off the coast of Alaska and stock it with some 20 breeding pairs of foxes – all for your wearing pleasure. Be unnerved here> This 1929 Promotional Project Photograph Album details the Western Maryland Railway – a (primarily) coal & freight hauling operation – with images of the diverse aspects & views of the port facilities & docks, of the ‘up-to-date’ buildings & even some freight moving mechanisms (spiral chutes & cranes, etc). An outstanding, possibly unique album documenting local pre-depression Baltimore history, as well as the capital improvement efforts of one of Maryland’s major transportation firms! Love automotive and locomotive history? This is the album for you…

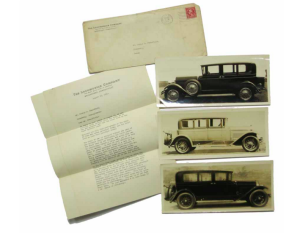

This 1929 Promotional Project Photograph Album details the Western Maryland Railway – a (primarily) coal & freight hauling operation – with images of the diverse aspects & views of the port facilities & docks, of the ‘up-to-date’ buildings & even some freight moving mechanisms (spiral chutes & cranes, etc). An outstanding, possibly unique album documenting local pre-depression Baltimore history, as well as the capital improvement efforts of one of Maryland’s major transportation firms! Love automotive and locomotive history? This is the album for you…