This month has been a big one here at Tavistock Books! We celebrate our 25th anniversary, along with the one-year anniversary of fearless Aide-de-Camp Margueritte Peterson. We’re also proud that this month we hit the 10,000-visitor mark for our blog. To recognize this occasion, we humbly present the top ten blog articles of all time. Hope you enjoy reading!

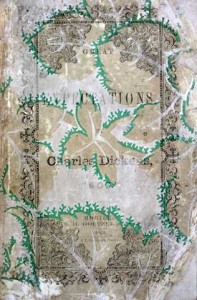

1. The Two Endings of Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations

1. The Two Endings of Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations

When Charles Dickens finished Great Expectations and sent it off to his publishers, he was quite pleased with himself. Then he showed a copy to friend and fellow author Edward Bulwer-Lytton, who, according to Dickens, “was so very anxious that I should alter the end…and stated his reasons so well, that I have resumed the wheel, and taken another turn at it.” The book’s dual endings present complications for critics and collectors alike. Read More>>

2. Why Did Charles Dickens Write Ghost Stories for Christmas?

For the Victorians, Christmas wasn’t complete without a great ghost story! Charles Dickens certainly catered to this preference with his beloved Christmas Carol and a number of other Christmas tales. But why ghost stories? The holiday–once forbidden by Oliver Cromwell–has its roots in pagan rituals, which included telling “winter’s tales,” that is, ghost stories. Read More>>

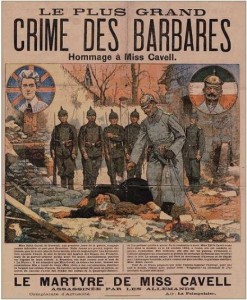

3. Edith Cavell: Nurse, Humanitarian, and…Traitor?

3. Edith Cavell: Nurse, Humanitarian, and…Traitor?

Edith Cavell quickly earned a reputation as an excellent nurse, and during World War I she found herself with another set of duties. Along with other nurses, Cavell was recruited by the British Secret Intelligence Service to collect information about the Germans. She eventually put that mission aside, preferring to funnel British and French soldiers to neutral Holland. Cavell raised suspicion, and the Germans arrested her for treason. Cavell was convicted and executed, a move that provided plenty of fodder for British and American propaganda machines. Read More>>

4. Alexander Pope’s Legacy of Satire and Scholarship

History has not always been kind to Alexander Pope, and neither were his contemporary critics. The poet published his earliest extant work at only twelve years old and went on to found the Scriblerus Club alongside celebrated authors John Gay and Jonathan Swift. Thanks to the guidance and support of Swift, Pope was able to do what few authors of the era managed to accomplish: he made a comfortable living with the pen, mostly due to his ingenious translation of Homer’s Iliad. Read More>>

5. A Brief History of Propaganda

Propaganda has existed for ages; the Behistun Inscription, written around 515 BCE details King Darius I’s glorious victory. But the Catholic Church gave us the word itself and formalized the use of propaganda, most notably when Pope Urban II needed to bolster support for the Crusades. The literacy boom of the nineteenth century actually drove the production of more propaganda, as politicians had to sway the opinions of a more informed public. World War I saw the first large-scale propaganda production. Britain even enlisted its best authors, like AA Milne, to create pro-war propaganda. Read More>>

6. Charles Dickens Does Boston

Charles Dickens’ first trip to America began promisingly enough; he was immediately mobbed by adoring fans. Dickens fell in love with Boston, declaring the city “what I would like the whole United States to be.” But the trip turned sour when the young author insisted on addressing the issue of international copyright law at every turn. He was also appalled by the way slavery was practiced in the South and by Americans’ lack of social graces. Dickens documented his impressions of the United States in American Notes, which immediately alienated his Continental readers. Read More>>

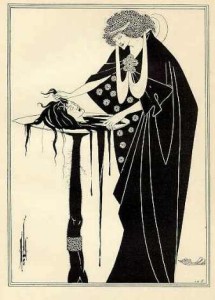

7. Oscar Wilde, Dickens Detractor and “Inventor” of Aubrey Beardsley

7. Oscar Wilde, Dickens Detractor and “Inventor” of Aubrey Beardsley

We remember Oscar Wilde just as much for his oversize personality as we do for his authorial excellence. Wilde’s ego often led to strange relationships with fellow authors, most notably Bram Stoker, Charles Dickens, and Aubrey Beardsley. Wilde lost a love to Stoker, railed against Dickens’ sentimentality, and claimed that Beardsley had Wilde to thank for his career. For rare book collectors, Oscar Wilde epitomizes the way that single-author collections can (and should) include works by other authors. Read More>>

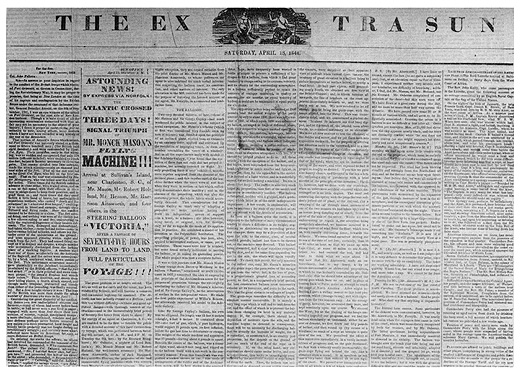

8. The Six Hoaxes of Edgar Allan Poe

Edgar Allan Poe called his time “the epoch of the hoax,” and the horror writer couldn’t have been happier about it. Poe was a great lover of hoaxes, even attempting several himself. He forged a note from a supposed lunar inhabitant and penned a fake journal from an explorer. Poe even undertook one hoax to dissuade people from going West during the Gold Rush. But Poe’s efforts only proved that he should have stuck to poetry and fiction; he hardly convinced anyone that his hoaxes were real. Read More>>

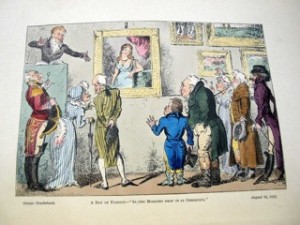

9. George Cruikshank: “Modern Hogarth,” Teetotaler, and Philanderer

George Cruikshank followed in his father’s footsteps, building a reputation as a preeminent illustrator of his time. Political from the beginning of his career, Cruikshank was openly racist and patriotic. He adopted an incredibly moralistic tone about drinking. That uncompromising campaign for temperance ultimately became a wedge between Cruikshank and Charles Dickens. After Cruikshank’s death, however, his wife discovered that he’d been leading a secret life–and had fathered eleven children with the family’s former servant. Read More>>

10. The Millerites an the Great Disappointment

The Seventh-Day Adventist Church arose from a great failure. The nineteenth century saw a revival in millinarianism, the belief that a drastic event or movement would suddenly change the course of society as outlined in the book of Revelation. William Miller stepped forward as a sort of prophet, arguing that Jesus would certainly return in 1843 or 1844. His followers, called the Millerites, embraced his predictions–until the days passed and nothing happened. They broke into a number of different sects, one of which developed into the Seventh-Day Adventist Church. Read More>>