CASEY AT THE BAT

BY: Ernest Lawrence Thayer

A Ballad of the Republic, Sung in the Year 1888

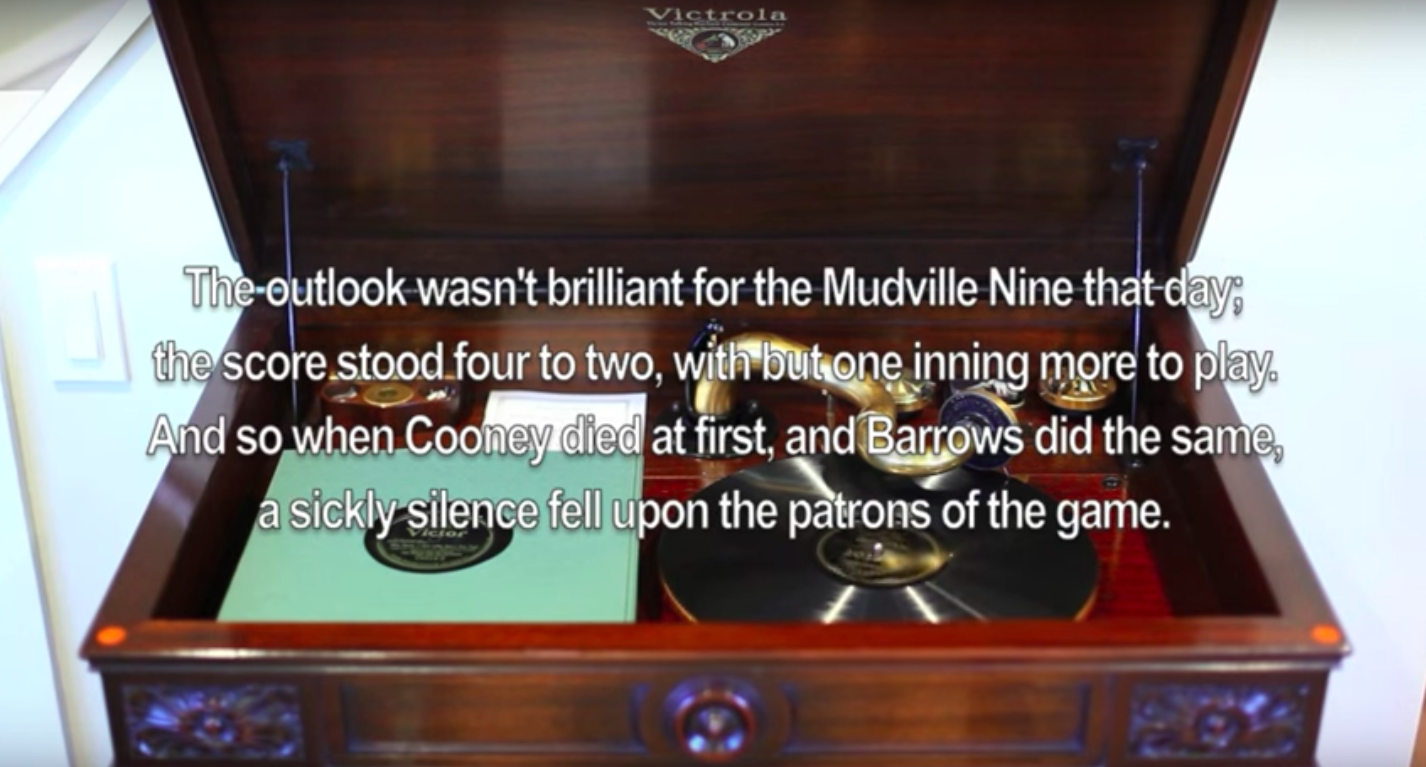

The outlook wasn’t brilliant for the Mudville nine that day;

The score stood four to two with but one inning more to play.

And then when Cooney died at first, and Barrows did the same,

A sickly silence fell upon the patrons of the game.

A straggling few got up to go in deep despair. The rest

Clung to that hope which springs eternal in the human breast;

They thought if only Casey could but get a whack at that—

We’d put up even money now with Casey at the bat.

But Flynn preceded Casey, as did also Jimmy Blake,

And the former was a lulu and the latter was a cake;

So upon that stricken multitude grim melancholy sat,

For there seemed but little chance of Casey’s getting to the bat.

But Flynn let drive a single, to the wonderment of all,

And Blake, the much despised, tore the cover off the ball;

And when the dust had lifted, and men saw what had occurred,

There was Jimmy safe at second and Flynn a-hugging third.

Then from 5,000 throats and more there rose a lusty yell;

It rumbled through the valley, it rattled in the dell;

It knocked upon the mountain and recoiled upon the flat,

For Casey, mighty Casey, was advancing to the bat.

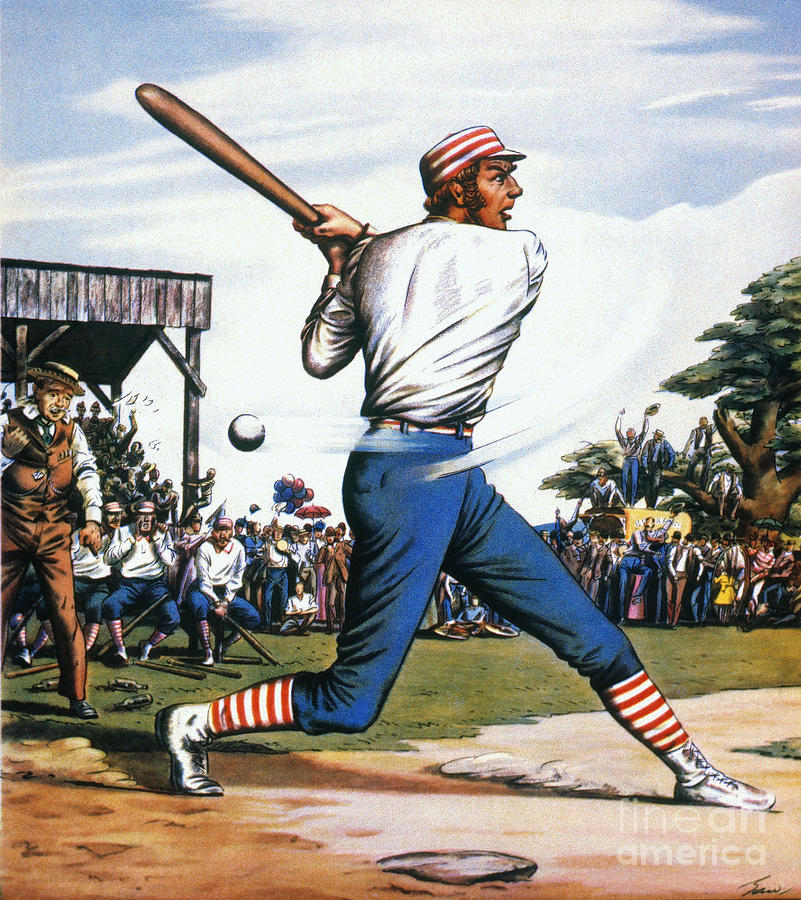

There was ease in Casey’s manner as he stepped into his place;

There was pride in Casey’s bearing and a smile on Casey’s face.

And when, responding to the cheers, he lightly doffed his hat,

No stranger in the crowd could doubt ’twas Casey at the bat.

Ten thousand eyes were on him as he rubbed his hands with dirt;

Five thousand tongues applauded when he wiped them on his shirt.

Then while the writhing pitcher ground the ball into his hip,

Defiance gleamed in Casey’s eye, a sneer curled Casey’s lip.

And now the leather-covered sphere came hurtling through the air,

And Casey stood a-watching it in haughty grandeur there.

Close by the sturdy batsman the ball unheeded sped—

“That ain’t my style,” said Casey. “Strike one,” the umpire said.

From the benches, black with people, there went up a muffled roar,

Like the beating of the storm-waves on a stern and distant shore.

“Kill him! Kill the umpire!” shouted some one on the stand;

And it’s likely they’d have killed him had not Casey raised his hand.

With a smile of Christian charity great Casey’s visage shone;

He stilled the rising tumult; he bade the game go on;

He signaled to the pitcher, and once more the spheroid flew;

But Casey still ignored it, and the umpire said, “Strike two.”

“Fraud!” cried the maddened thousands, and echo answered fraud;

But one scornful look from Casey and the audience was awed.

They saw his face grow stern and cold, they saw his muscles strain,

And they knew that Casey wouldn’t let that ball go by again.

The sneer is gone from Casey’s lip, his teeth are clinched in hate;

He pounds with cruel violence his bat upon the plate.

And now the pitcher holds the ball, and now he lets it go,

And now the air is shattered by the force of Casey’s blow.

Oh, somewhere in this favored land the sun is shining bright;

The band is playing somewhere, and somewhere hearts are light,

And somewhere men are laughing, and somewhere children shout;

But there is no joy in Mudville—mighty Casey has struck out.

Do you even truly consider yourself American if you don’t know at least one stanza of this poem by heart? Unlike the mighty and fearless leader of Tavistock Books (and the San Francisco Giants’ #1 Fan) Vic Zoschak, I know relatively zilch about baseball. I know there are two teams, I know there are some innings, and I know the hot dogs are as delicious as they are terrible for you. So yeah, I basically know nothing about baseball. But Casey? Oh, I know all about that self-confident dud.

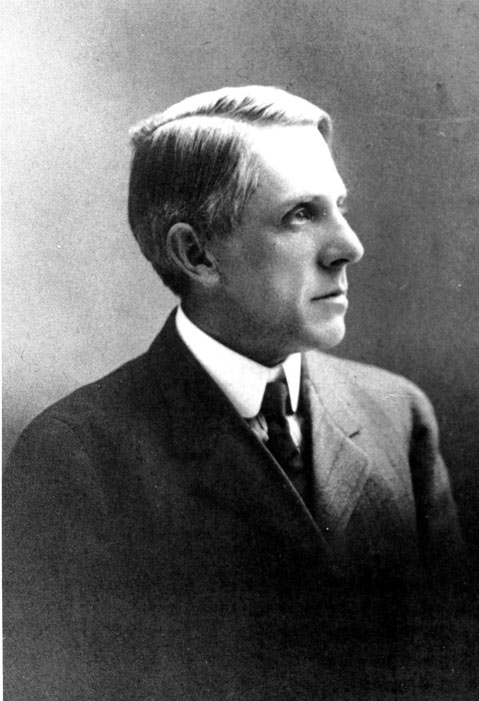

Ernest Thayer was a Harvard educated author, who began working at the age of 24 as a humor columnist for The San Francisco Examiner. On June 3rd, 1888, the elusive author “Phin” published a poem that would become a backbone of both American poetry and baseball. Thayer did not receive credit for the poem for several months (as he was not a boastful man), and when he finally did he was surprisingly close-lipped about it all. He never revealed whether he based the game or the character of Casey on a real player, though many have put forth possibilities.

Ernest Thayer was a Harvard educated author, who began working at the age of 24 as a humor columnist for The San Francisco Examiner. On June 3rd, 1888, the elusive author “Phin” published a poem that would become a backbone of both American poetry and baseball. Thayer did not receive credit for the poem for several months (as he was not a boastful man), and when he finally did he was surprisingly close-lipped about it all. He never revealed whether he based the game or the character of Casey on a real player, though many have put forth possibilities.

Actor William DeWolf Hopper was the first to read the poem aloud onstage – on August 14th, 1888 (Thayer’s birthday, as a matter of fact) at the Wallack Theatre in New York City. Present were the Chicago and New York baseball teams – the White Stockings and the Giants. Many of Hopper’s recitations of the poem can be heard today, as he became the official orator of the poem – and by the end of his life had recited it over 10,000 times. Thayer read it aloud just once, at a Harvard class reunion in 1895, which finally settled any doubts Americans had on the wordsmith and creator of the poem. Despite the fact that many knew of Thayer’s authorship, his lack of comment and humble nature had caused many to doubt it throughout the years!

Click here to listen to DeWolf Hopper reciting Casey at the Bat

Thayer lived in California for the bulk of his life working at the San Francisco Examiner, eventually moving in 1912 to Santa Barbara where he lived until he passed away at the age of 77.

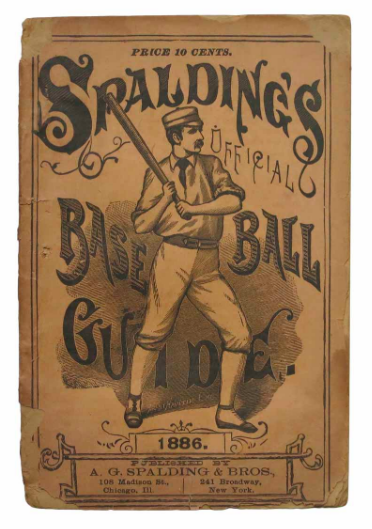

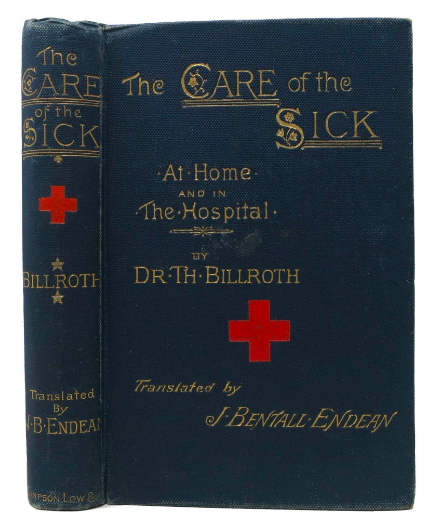

Here is one of our many baseball offerings (we mentioned that Vic was a GIANT baseball fan, right? (See what I did there? That man loves the Giants.) Printed just two years prior to Thayer’s poem publication, this 125 page wrappered booklet claims to be the “Complete Hand Book of the National Game of Baseball.” Find out everything Thayer knew about the game here!

Emily Dickinson was born in Amherst, Massachusetts, on December 10th, 1830. She was the second of three children, with one elder brother named Austin and a younger sister, Lavinia. Her father was not only a lawyer by trade, but a trustee of Amherst College, where his father had been one of the founders of the school. With their background in education, the Dickinson children were given a thorough education for the time, certainly when it came to the two girls. At the age of 10 Emily and her sister began their studies at Amherst Academy, which had begun to allow female students a scant two years before their studies began. Emily remained at the school for seven years, studying math, literature, latin, botany, history, and all manner of respected academia. Upon finishing her studies at the Academy in 1847, Dickinson enrolled in the Mount Holyoke Female Seminary (now Mount Holyoke College). Although the Seminary was only 10 miles from her home, Dickinson only remained at the school for 10 months before returning home – for reasons many have tried to unearth but none can be sure of.

Emily Dickinson was born in Amherst, Massachusetts, on December 10th, 1830. She was the second of three children, with one elder brother named Austin and a younger sister, Lavinia. Her father was not only a lawyer by trade, but a trustee of Amherst College, where his father had been one of the founders of the school. With their background in education, the Dickinson children were given a thorough education for the time, certainly when it came to the two girls. At the age of 10 Emily and her sister began their studies at Amherst Academy, which had begun to allow female students a scant two years before their studies began. Emily remained at the school for seven years, studying math, literature, latin, botany, history, and all manner of respected academia. Upon finishing her studies at the Academy in 1847, Dickinson enrolled in the Mount Holyoke Female Seminary (now Mount Holyoke College). Although the Seminary was only 10 miles from her home, Dickinson only remained at the school for 10 months before returning home – for reasons many have tried to unearth but none can be sure of. Though throughout her late teens Dickinson seemed to enjoy life in Amherst socially, and was certainly already writing poetry (a family friend Benjamin Franklin Newton hinted in letters before his death in this time that he had hoped to live to see her reach the success he knew possible), by her twenties Emily was already feeling a melancholy pull, exacerbated by her emotions when it came to death, and the deaths of those around her. Her mother’s many chronic illnesses kept Emily often at home, and by the 1860s (Dickinson’s 30s) she had already largely pulled out of the public eye. By her 40s, Dickinson rarely left her room, and preferred to speak with visitors through her door rather than face-to-face. Unbeknownst to any, Dickinson worked tirelessly throughout this period on her poetry, and by the end of her life had amassed a collection of roughly 1,800 poems neatly written in hand sewn journals. That being said, less than one dozen of her poems would be published during her lifetime. The first book of her poetry, published four years after her death on May 15th, 1886 by her sister Lavinia, was a resounding success. In less than two years, eleven editions of the first book had been printed, and her words spread across nations.

Though throughout her late teens Dickinson seemed to enjoy life in Amherst socially, and was certainly already writing poetry (a family friend Benjamin Franklin Newton hinted in letters before his death in this time that he had hoped to live to see her reach the success he knew possible), by her twenties Emily was already feeling a melancholy pull, exacerbated by her emotions when it came to death, and the deaths of those around her. Her mother’s many chronic illnesses kept Emily often at home, and by the 1860s (Dickinson’s 30s) she had already largely pulled out of the public eye. By her 40s, Dickinson rarely left her room, and preferred to speak with visitors through her door rather than face-to-face. Unbeknownst to any, Dickinson worked tirelessly throughout this period on her poetry, and by the end of her life had amassed a collection of roughly 1,800 poems neatly written in hand sewn journals. That being said, less than one dozen of her poems would be published during her lifetime. The first book of her poetry, published four years after her death on May 15th, 1886 by her sister Lavinia, was a resounding success. In less than two years, eleven editions of the first book had been printed, and her words spread across nations.

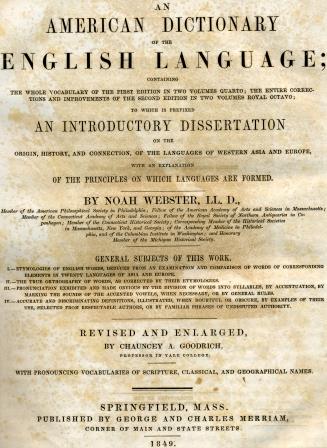

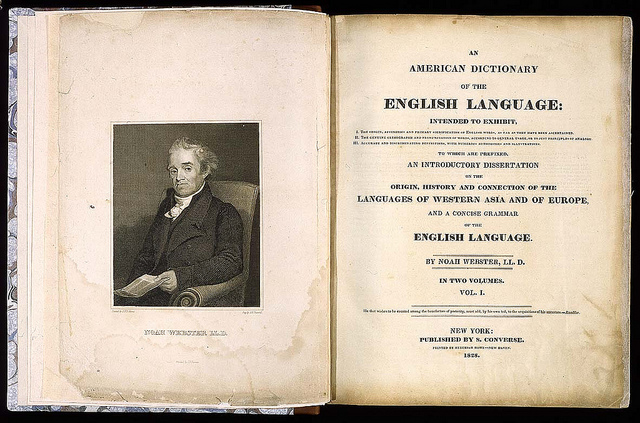

Webster married Rebecca Greenleaf in 1789, and as she was of good breeding (man, I don’t get to use that phrase often enough) he was able to join higher levels of society in Connecticut than he had been. (They would later have 8 children, but that is neither here nor there.) Due to his beliefs in the revolution and conviction in America’s greatness, one Alexander Hamilton loaned him $1,500 in 1793 to move to New York and become the editor for the Federalist Papers. For the next few decades, Webster spent much of his time being one of the most profuse authors of the time, especially when it came to political reports, but also in regard to textbooks and articles across the board.

Webster married Rebecca Greenleaf in 1789, and as she was of good breeding (man, I don’t get to use that phrase often enough) he was able to join higher levels of society in Connecticut than he had been. (They would later have 8 children, but that is neither here nor there.) Due to his beliefs in the revolution and conviction in America’s greatness, one Alexander Hamilton loaned him $1,500 in 1793 to move to New York and become the editor for the Federalist Papers. For the next few decades, Webster spent much of his time being one of the most profuse authors of the time, especially when it came to political reports, but also in regard to textbooks and articles across the board.

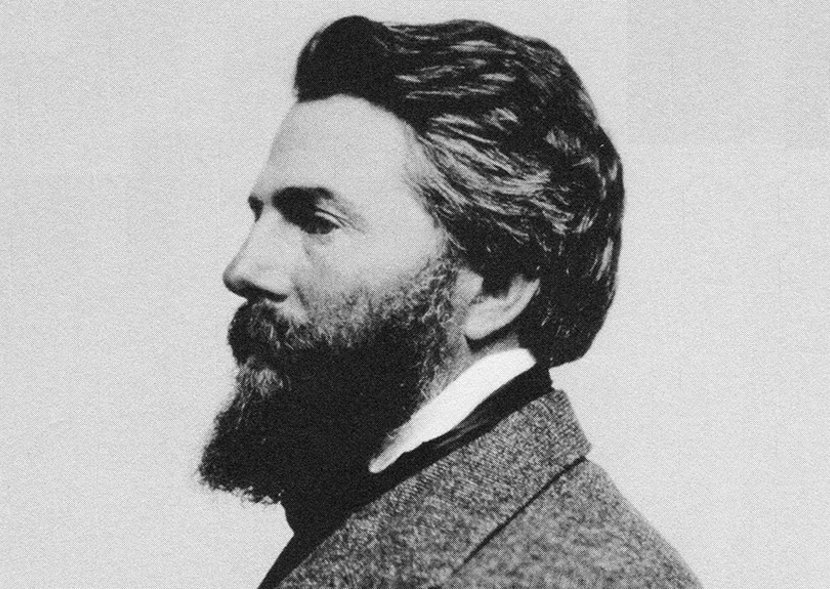

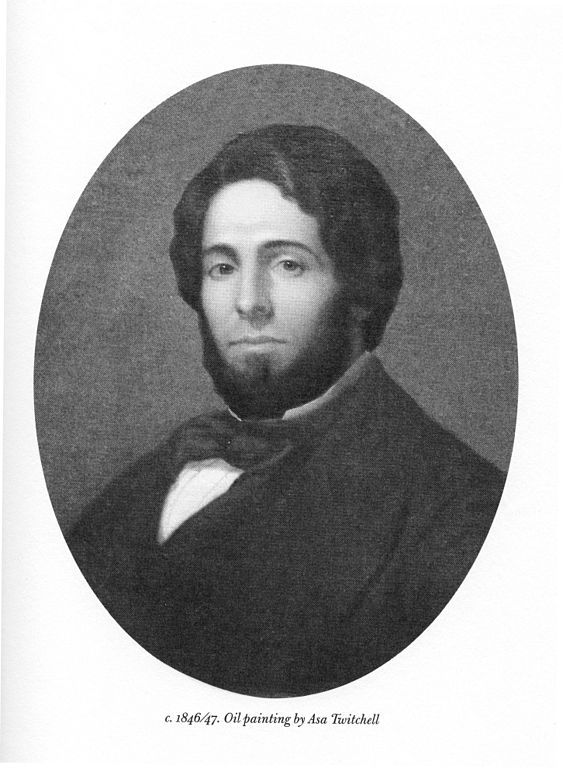

Herman Melvill (yes, that spelling is correct) was born in August of 1819 in New York City. He was the third of eight children born to a merchant and his wife. Though his parents have been described as loving and devoted, his father Allan’s money woes left much to be desired. Allan borrowed and spent well beyond his means, and after contracting what researchers imagine as pneumonia on a trip back to Albany from New York City, he abruptly passed away when Herman was merely 13 years old. Herman’s schooling ended as abruptly as his father’s life, and he was given a job as a clerk in the fur trade (his father’s business) by his uncle. Sometime around this time, Herman’s mother changed the spelling of their last name by adding an “e” to the end. History is still unsure as to why she would have done this – to sound more sophisticated, to hide from debt collectors… we may never know! But that simple “e” will live on forever, that is for sure.

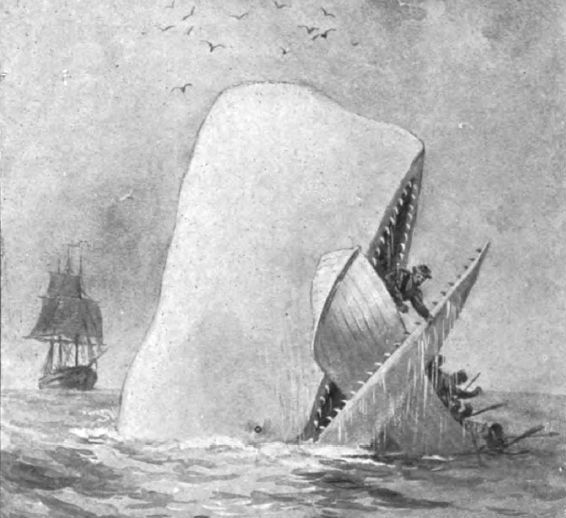

Herman Melvill (yes, that spelling is correct) was born in August of 1819 in New York City. He was the third of eight children born to a merchant and his wife. Though his parents have been described as loving and devoted, his father Allan’s money woes left much to be desired. Allan borrowed and spent well beyond his means, and after contracting what researchers imagine as pneumonia on a trip back to Albany from New York City, he abruptly passed away when Herman was merely 13 years old. Herman’s schooling ended as abruptly as his father’s life, and he was given a job as a clerk in the fur trade (his father’s business) by his uncle. Sometime around this time, Herman’s mother changed the spelling of their last name by adding an “e” to the end. History is still unsure as to why she would have done this – to sound more sophisticated, to hide from debt collectors… we may never know! But that simple “e” will live on forever, that is for sure. In May of 1831 Melville signed up as a “boy” (a newbie, for all intents and purposes) on a merchant ship called the St. Lawrence, and went from New York to Liverpool and back. That experience successful (and what with a longstanding obsession with the true story of the search for the white sperm whale called Mocha Dick), he decided to join the Acushnet for a whaling voyage in 1841. After a few months on board, Melville decided to jump ship with another deckhand in the Marquesas Islands after several reported disagreements with the captain of the ship. Expecting to come across cannibalistic natives, Melville was (unsurprisingly) pleased to find out that the natives were accommodating and friendly – a fact which he would later address in his 1845 novel Typee – semi-autobiographical in nature as it was based on his stay in the islands. Melville then experienced island and country hopping to an extreme degree, after boarding a boat from the Marquesas to Australia then continuing on whaling and merchant vessels visiting Tahiti, Oahu, Rio de Janeiro and Lima, Peru – among others. Eventually, Melville ended up back in Boston, Massachusetts.

In May of 1831 Melville signed up as a “boy” (a newbie, for all intents and purposes) on a merchant ship called the St. Lawrence, and went from New York to Liverpool and back. That experience successful (and what with a longstanding obsession with the true story of the search for the white sperm whale called Mocha Dick), he decided to join the Acushnet for a whaling voyage in 1841. After a few months on board, Melville decided to jump ship with another deckhand in the Marquesas Islands after several reported disagreements with the captain of the ship. Expecting to come across cannibalistic natives, Melville was (unsurprisingly) pleased to find out that the natives were accommodating and friendly – a fact which he would later address in his 1845 novel Typee – semi-autobiographical in nature as it was based on his stay in the islands. Melville then experienced island and country hopping to an extreme degree, after boarding a boat from the Marquesas to Australia then continuing on whaling and merchant vessels visiting Tahiti, Oahu, Rio de Janeiro and Lima, Peru – among others. Eventually, Melville ended up back in Boston, Massachusetts.

Barrie wrote several successful plays (and a couple flukes), but his third script brought him into contact with a young actress of the day – Mary Ansell – who would later, in 1894, become Barrie’s wife. For their union Barrie gifted Mary a St. Bernard puppy – who would become the inspiration for “Nana” in later years. They settled in London but kept a country home in Farnham, Surrey. In 1897 Barrie became acquainted with a nearby family – the Llewelyn Davies family.

Barrie wrote several successful plays (and a couple flukes), but his third script brought him into contact with a young actress of the day – Mary Ansell – who would later, in 1894, become Barrie’s wife. For their union Barrie gifted Mary a St. Bernard puppy – who would become the inspiration for “Nana” in later years. They settled in London but kept a country home in Farnham, Surrey. In 1897 Barrie became acquainted with a nearby family – the Llewelyn Davies family. Inspired largely by the stories he told to the Llewelyn Davies family, Barrie began to formulate a story of a boy who wouldn’t grow up, who flew around and had adventures. Not unlike Charles Dodgson’s Alice a century before, Barrie began to write his story into a play and once debuted in 1904, the play Peter Pan; or the Boy Who Wouldn’t Grow Up was an immediate success. George Bernard Shaw said of the performance, “ostensibly a holiday entertainment for children, but really a play for grown-up people” – a wonderful description of the meanings and metaphors found in Peter Pan. Though children may see the adventure story on the outside, the adults in the audience could see what was really at play (pun intended) – Barrie’s social commentary on the adult’s fear of time and growing old and losing their childish innocence and fun, to name just a few.

Inspired largely by the stories he told to the Llewelyn Davies family, Barrie began to formulate a story of a boy who wouldn’t grow up, who flew around and had adventures. Not unlike Charles Dodgson’s Alice a century before, Barrie began to write his story into a play and once debuted in 1904, the play Peter Pan; or the Boy Who Wouldn’t Grow Up was an immediate success. George Bernard Shaw said of the performance, “ostensibly a holiday entertainment for children, but really a play for grown-up people” – a wonderful description of the meanings and metaphors found in Peter Pan. Though children may see the adventure story on the outside, the adults in the audience could see what was really at play (pun intended) – Barrie’s social commentary on the adult’s fear of time and growing old and losing their childish innocence and fun, to name just a few.