By Margueritte Peterson

Normally our author blogs are based on a date in the life of said author – birthdays, publishing dates, even memorials to their deaths. I’d like to take this moment to say that this is not one of those types of dates. This blog is completely and utterly random… all because I recently dreamt about seeing a sunrise at Big Sur and decided to get to know one of the many authors who made the area their home… Mr. Henry Miller.

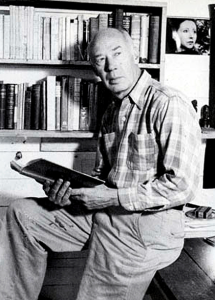

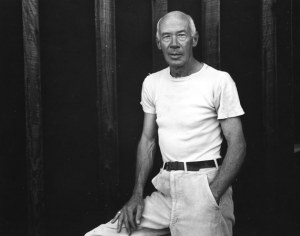

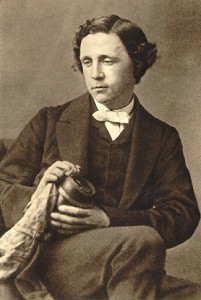

Henry Miller lived to the ripe old age of 88, and in less than a century managed to offend tens of thousands of people. His books were banned in not only states but entire countries. (The United States being one of them… yay for freedom of speech?) And why was this one man as taboo as sex before marriage was to Victorians? Because he dared. Well… dared in life and then proceeded to publish his daring activities. Miller was known for his free way of writing – a truly singular author in style, blending many different genres of literature (autobiography and philosophy, surrealism and social critique – to name a few) creating a truly unique voice. But one of the many aspects that set him apart from the crowd was the fact that his work was, at the least, semi-autobiographical in nature – and to describe the sexual exploits of a lonely man in Paris in the 30s was gutsy, to say the least. So what in Miller’s life was so audacious as to be banned in countries around the world? Well I’ll tell you…

Henry Miller lived to the ripe old age of 88, and in less than a century managed to offend tens of thousands of people. His books were banned in not only states but entire countries. (The United States being one of them… yay for freedom of speech?) And why was this one man as taboo as sex before marriage was to Victorians? Because he dared. Well… dared in life and then proceeded to publish his daring activities. Miller was known for his free way of writing – a truly singular author in style, blending many different genres of literature (autobiography and philosophy, surrealism and social critique – to name a few) creating a truly unique voice. But one of the many aspects that set him apart from the crowd was the fact that his work was, at the least, semi-autobiographical in nature – and to describe the sexual exploits of a lonely man in Paris in the 30s was gutsy, to say the least. So what in Miller’s life was so audacious as to be banned in countries around the world? Well I’ll tell you…

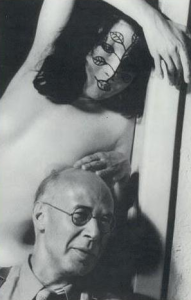

Miller was born the day after Christmas in 1891 and spent most of his childhood growing up in Brooklyn, New York. The author married his first wife (Beatrice Sylvas Wickens) young, and though the union produced his first child, daughter Barbara, in 1919, the marriage was not a happy one and the couple divorced in 1923. A short while after his divorce was finalized (so shortly, in fact, that it is quite likely Miller began the next relationship before the end of his first one) Miller married a dancer who went by the name June Mansfield. June would be much written about and discussed for both her beauty and her deceptive and slightly challenging nature. During his marriage to Mansfield, Miller would spend much time abroad, particularly in Paris (and continued to live there for 5 years after she divorced him by proxy in 1934). His time in Paris was very influential to his writing, as he became ingratiated with a literary community there – so far as to be financed by Anais Nin and her husband Ian Hugo for most of the 1930s while he wrote in (what would today be considered) poverty. Nin and Miller were lovers and their relationship would be common knowledge once Nin’s private diaries were published (with both’s permission) in 1969. The pair would remain friends for life.

The Dust Jacket on his first published work, “Tropic of Cancer” (1934) came with a warning to readers that it was not to be distributed in the United States or in Great Britain. Miller’s work detailed varied sexual experiences that were considered extremely scandalous (perhaps because they were based in truth!) for the time and for a great number of years his work was banned in two of the most (supposedly) democratic countries in the world. Luckily for the author, however, the censorship and scandal surrounding his work grew him a fantastical reputation in underground literary society – and despite his books being banned he was world-famous and well-known. Though Miller eventually grew tired of being respected for writing what, to some, came across as smut or erotica, he did not fight his reputation (being married and divorced five times certainly didn’t help to quell the image of his excessive sexuality). He is known to have inspired an entire group of writers that later would become known as the Beat Generation (Jack Kerouac cited Miller as one of his literary idols). For that he is considered one of the forerunners of modern literature, and is to be revered for his help in freeing up the “mind” for future authors and audiences.

The Dust Jacket on his first published work, “Tropic of Cancer” (1934) came with a warning to readers that it was not to be distributed in the United States or in Great Britain. Miller’s work detailed varied sexual experiences that were considered extremely scandalous (perhaps because they were based in truth!) for the time and for a great number of years his work was banned in two of the most (supposedly) democratic countries in the world. Luckily for the author, however, the censorship and scandal surrounding his work grew him a fantastical reputation in underground literary society – and despite his books being banned he was world-famous and well-known. Though Miller eventually grew tired of being respected for writing what, to some, came across as smut or erotica, he did not fight his reputation (being married and divorced five times certainly didn’t help to quell the image of his excessive sexuality). He is known to have inspired an entire group of writers that later would become known as the Beat Generation (Jack Kerouac cited Miller as one of his literary idols). For that he is considered one of the forerunners of modern literature, and is to be revered for his help in freeing up the “mind” for future authors and audiences.

![The Honorable David Culbreth [Colbreth] Broderick.](http://blog.tavbooks.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/broderick1-256x300.jpg)