Plenty of stories make ripples. The ripples they create inspire some, and makes others look deeply into themselves. Some stories can change the world – and frequently have! We would argue that one such book was 1984, the dystopian novel written by George Orwell in 1949. Now that 1984 (the year) has come and is long gone, we thought it might be interesting to take a look at this popular novel and see how its ripples continue to affect society today.

1984 was published on June 8th, 1949 – 73 years ago today. It would be English author George Orwell’s last work, as he was dying from tuberculosis while writing it, and passed away less than a year after its publication. Orwell himself was an atheist who supported democracy and vehemently opposed totalitarianism (of course). He was a proponent of simple pleasures, and was a fan of all traditional British delights – fish and chips, a strong cup of tea, a nice pub or chat by a fire, to name a few. It is no wonder how this kind of individual was able to write 1984, a book that played on a fear of oppressive government sanctions and a powerlessness to enjoy the simple pleasures in life.

For those that haven’t read it since their school days, 1984 follows the protagonist Winston Smith as he navigates his feelings towards an undemocratic governmental regime. Smith realizes he is doomed quite early on in the tale, as he buys a journal at a small antiques shop (on a black market of sorts), in order to write his “illegal” thoughts down in. Smith wonders often at the idea of the rebels, constantly interpreting the actions of those around him as either for or against the regime – he rarely views anything as a simple personal interaction. He begins an illicit romantic relationship with a woman named Julia after she hands him a secret note that says “I love you” (yes, after Winston is sure her interest in him is as a government spy). They are happy and in love, though Winston’s interest in rebelling against the regime is significantly stronger than Julia’s. As Winston grows more interested in breaking away, he becomes closer with Mr. Charrington, the owner of the shop that sold him the journal. Winston also believes his direct superior at work is a member of the rebellious “Brotherhood”. Winston and Julia are eventually brought before both of them and invited to join the Brotherhood, before it is revealed that both Charrington and O’Brien (his superior) are actually members of the government’s “Thought Police” task force and Winston and Julia are arrested. After being tortured, interrogated and brainwashed for months, a final act involving fear, rats and selling out each other finally break the couple, individually. They are released back into normal society in Oceania, loving “Big Brother” as newly minted members of the tyrannical and ruthless regime.

While considering the above as a highly abridged Cliff Notes version of 1984, we look toward the meaning behind the novel and how its ripples still affect us today. We are lucky to live in a non-extremist, democratic society. We are obsessed with our Constitutional rights – one of the most important being the right to free speech, as Winston unfortunately did not have. As an article in The Atlantic stated “It’s almost impossible to talk about propaganda, surveillance, authoritarian politics, or perversions of truth without dropping a reference to 1984.” And that is true. “Big Brother” is a household term, a terrifying nightmarish possibility of a government that is allowed to become too involved in the lives of its citizens. Once again, we are lucky that we do not live in such a society. As music critic Dorian Lynskey (author of The Ministry of Truth: The Biography of George Orwell’s 1984) writes “By definition, a country in which you are free to read Nineteen Eighty-Four is not the country described in Nineteen Eighty-Four“. But the year of Trump’s inauguration as President saw the rise of 1984 back to the best-seller list. Why? Because many Americans worried about the beginning of the decline of democracy in our country. After all, the rise of a totalitarian administration is certainly something to fear.

But occasionally, we’ve had cause to ask if the totalitarian we fear may, in fact, be something within ourselves. In today’s world, we already allow companies, rather than the government, to watch our every move. It makes life easier for us, and we’ve had no visibly apparent reason to believe it is otherwise affecting our lives. We police the things each other say online, constantly. To both positive and negative ends. A problem today’s America faces isn’t that we are being oppressed by an authoritarian regime, but that because of the newspeak that we follow or watch we are too divisive to be able to be on the same page about anything whatsoever. It seems the news (and therefore groups of people), fall at two very far ends of a spectrum – without the ability to work together to make changes any which way. Unfortunately causing us to be at a consistent stalemate, daily. Normally we don’t quote lengthy paragraphs from others, but I believe George Packer said it correctly in an article about 1984:

“We are living with a new kind of regime that didn’t exist in Orwell’s time. It combines hard nationalism—the diversion of frustration and cynicism into xenophobia and hatred—with soft distraction and confusion: a blend of Orwell and Huxley, cruelty and entertainment. The state of mind that the Party enforces through terror in 1984, where truth becomes so unstable that it ceases to exist, we now induce in ourselves… Today the problem is too much information from too many sources, with a resulting plague of fragmentation and division—not excessive authority but its disappearance, which leaves ordinary people to work out the facts for themselves, at the mercy of their own prejudices and delusions.” 1984 hasn’t become obsolete, on the contrary – it is more important than ever that we look to it as the cautionary tale it was meant as. Let us not follow anyone blindly – and perhaps we can stop screaming at each other long enough to help each other. To see the problems in our society and make changes necessary for the safety, health and happiness of us all.

And whatever you do, don’t ever trust the antiques shop owners selling books, journals and other trinkets… obviously it is the quiet ones you need to watch out for!

As time went on and interest in her intelligence, loveliness, refinement and gentility grew, Juliette became friendly with all manner of people. Some of the most notorious members of her salon were François-René de Chateaubriand (a French politician, diplomat, activist, historian and writer who ended up as one of Juliette’s life-long friends), Benjamin Constant (Swiss-French political activist and writer), Prince Augustus of Prussia (whose proposal she would ultimately reject), and the political Madame Germaine de Staël. Juliette enjoyed almost unprecedented independence in her ability to entertain and act as she saw fit – she also received many proposals, and was “courted” by many men, but never, as far as history is concerned, betrayed her husband. People were attracted to Juliette not solely because of her good looks, but because of her academic and literary prowess, her interest in social and political endeavors, and her apparent ability to charm a room with a single glance, smile or comment. Juliette Récamier was the epitome of an esteemed lady – a patron, a scholar, a magnetic and irresistible personality, and a beautiful and charismatic individual. Political and intellectual persons flocked to her sitting room, and the discourses had there (both with Madame Récamier and with each other) can be credited with several of the ideas and large-scale changes in the turbulence of the French politics of the day.

As time went on and interest in her intelligence, loveliness, refinement and gentility grew, Juliette became friendly with all manner of people. Some of the most notorious members of her salon were François-René de Chateaubriand (a French politician, diplomat, activist, historian and writer who ended up as one of Juliette’s life-long friends), Benjamin Constant (Swiss-French political activist and writer), Prince Augustus of Prussia (whose proposal she would ultimately reject), and the political Madame Germaine de Staël. Juliette enjoyed almost unprecedented independence in her ability to entertain and act as she saw fit – she also received many proposals, and was “courted” by many men, but never, as far as history is concerned, betrayed her husband. People were attracted to Juliette not solely because of her good looks, but because of her academic and literary prowess, her interest in social and political endeavors, and her apparent ability to charm a room with a single glance, smile or comment. Juliette Récamier was the epitome of an esteemed lady – a patron, a scholar, a magnetic and irresistible personality, and a beautiful and charismatic individual. Political and intellectual persons flocked to her sitting room, and the discourses had there (both with Madame Récamier and with each other) can be credited with several of the ideas and large-scale changes in the turbulence of the French politics of the day.

During her time in France, Mary witnessed the execution of King Louis XIV, even saw some of her friends executed when the Jacobins took power, was refused her requests to leave the country, and lived with American adventurer Gilbert Imlay, with whom she had a passionate affair. (“Which of these things is not like the other?”, you may as well ask!) Though all of her experiences greatly influenced her thoughts and views of humanity, she decided to put her individuality and power to the test by living unmarried with a man, and bearing a child by him, named Fanny after her dearest deceased friend. Wollstonecraft and Imlay remained together long enough to do a bit of traveling, and for Mary to publish two other works – An Historical and Moral View of the Origin and Progress of the French Revolution, and a introspective and personal travelogue, Letters Written During a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway and Denmark. After Imlay left her, Wollstonecraft returned to England to pursue him, and after bouts of suicidal tendencies and depression fell back into Joseph Johnson’s literary circle. Eventually, Mary began striking up a friendship, and then a passionate love affair with William Godwin. Of her work (her travel Letters, in particular) Godwin wrote, “If ever there was a book calculated to make a man in love with its author, this appears to me to be the book. She speaks of her sorrows, in a way that fills us with melancholy, and dissolves us in tenderness, at the same time that she displays a genius which commands all our admiration.” Despite not being proponents of marriage in general, the two wed shortly before Wollstonecraft’s second child was born – her daughter Mary, who would later go on to write Frankenstein as Mary Shelley (to read our blog on the second brilliant female mind in the family, click

During her time in France, Mary witnessed the execution of King Louis XIV, even saw some of her friends executed when the Jacobins took power, was refused her requests to leave the country, and lived with American adventurer Gilbert Imlay, with whom she had a passionate affair. (“Which of these things is not like the other?”, you may as well ask!) Though all of her experiences greatly influenced her thoughts and views of humanity, she decided to put her individuality and power to the test by living unmarried with a man, and bearing a child by him, named Fanny after her dearest deceased friend. Wollstonecraft and Imlay remained together long enough to do a bit of traveling, and for Mary to publish two other works – An Historical and Moral View of the Origin and Progress of the French Revolution, and a introspective and personal travelogue, Letters Written During a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway and Denmark. After Imlay left her, Wollstonecraft returned to England to pursue him, and after bouts of suicidal tendencies and depression fell back into Joseph Johnson’s literary circle. Eventually, Mary began striking up a friendship, and then a passionate love affair with William Godwin. Of her work (her travel Letters, in particular) Godwin wrote, “If ever there was a book calculated to make a man in love with its author, this appears to me to be the book. She speaks of her sorrows, in a way that fills us with melancholy, and dissolves us in tenderness, at the same time that she displays a genius which commands all our admiration.” Despite not being proponents of marriage in general, the two wed shortly before Wollstonecraft’s second child was born – her daughter Mary, who would later go on to write Frankenstein as Mary Shelley (to read our blog on the second brilliant female mind in the family, click

Paine’s pamphlets, especially Common Sense, were immediate successes. Common Sense was published on January 10th, 1776, and was signed anonymously, “by an Englishman”. Within the first three months of its existence 100,000 copies were sold throughout the colonies. He employed his eloquence to fan the flames of anger at the British monarchy for their abuses. While published after the start of the American Revolution (which began in April 1775), it served to bolster enthusiasm for the cause, to inspire many and to aid in the confidence of those fighting for freedom. Common Sense largely upholds the ideals of republicanism and encouragement for freedom, and spends some time encouraging readers to join the Continental Army. He advocates an extreme change, a total break in the narrative of history. Though his ideas were not necessarily original nor unheard of, Paine’s method and way of speaking to the public made his pamphlet one of the most popular Revolutionary works in existence. In that vein, Paine became one of the most influential revolutionary writers in history.

Paine’s pamphlets, especially Common Sense, were immediate successes. Common Sense was published on January 10th, 1776, and was signed anonymously, “by an Englishman”. Within the first three months of its existence 100,000 copies were sold throughout the colonies. He employed his eloquence to fan the flames of anger at the British monarchy for their abuses. While published after the start of the American Revolution (which began in April 1775), it served to bolster enthusiasm for the cause, to inspire many and to aid in the confidence of those fighting for freedom. Common Sense largely upholds the ideals of republicanism and encouragement for freedom, and spends some time encouraging readers to join the Continental Army. He advocates an extreme change, a total break in the narrative of history. Though his ideas were not necessarily original nor unheard of, Paine’s method and way of speaking to the public made his pamphlet one of the most popular Revolutionary works in existence. In that vein, Paine became one of the most influential revolutionary writers in history.

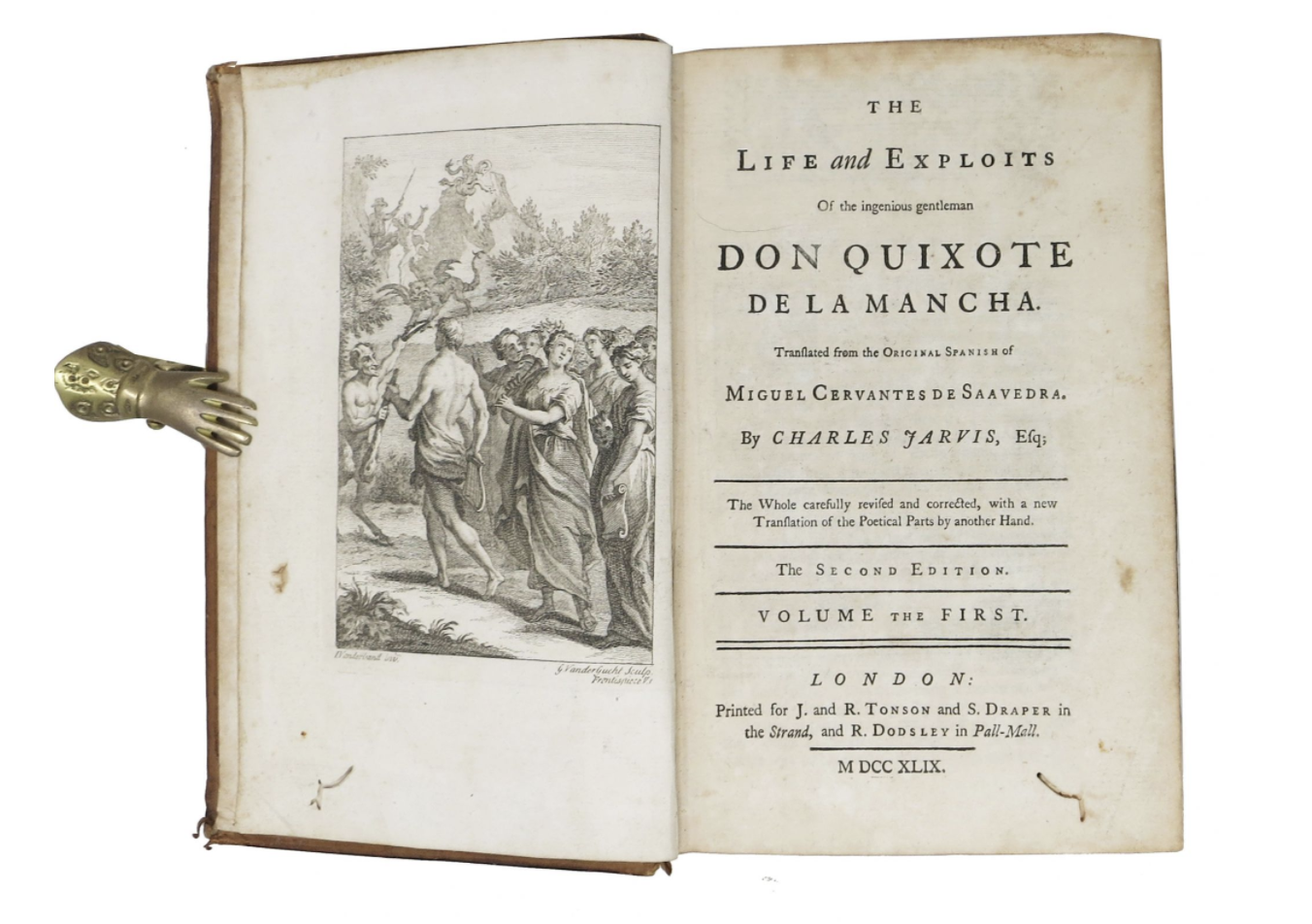

Throughout this time, Cervantes published a few plays and some poems, none of any great significance, and none that provided a living for the man and his family. By 1605, Cervantes hadn’t been “properly” published in almost 20 years! Nevertheless, he began writing a work he considered a satire – he challenged a “form of literature that had been a favourite for more than a century, explicitly stating his purpose was to undermine ‘vain and empty’ chivalric romances. He wrote about the common man. He used everyday lingo, normal conversation rather than epic speeches – it was considered a great success. Though there was a great amount of time between the two parts of the work, its popularity did not wane. The first part is considered the more popular of the two, with its comedic characterizations and its hilarity, while the second part is considered more introspective and critical, with greater characterization of the individuals in the story.

Throughout this time, Cervantes published a few plays and some poems, none of any great significance, and none that provided a living for the man and his family. By 1605, Cervantes hadn’t been “properly” published in almost 20 years! Nevertheless, he began writing a work he considered a satire – he challenged a “form of literature that had been a favourite for more than a century, explicitly stating his purpose was to undermine ‘vain and empty’ chivalric romances. He wrote about the common man. He used everyday lingo, normal conversation rather than epic speeches – it was considered a great success. Though there was a great amount of time between the two parts of the work, its popularity did not wane. The first part is considered the more popular of the two, with its comedic characterizations and its hilarity, while the second part is considered more introspective and critical, with greater characterization of the individuals in the story.

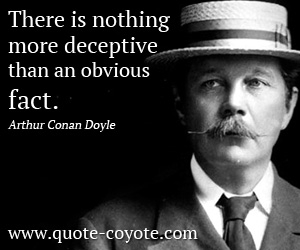

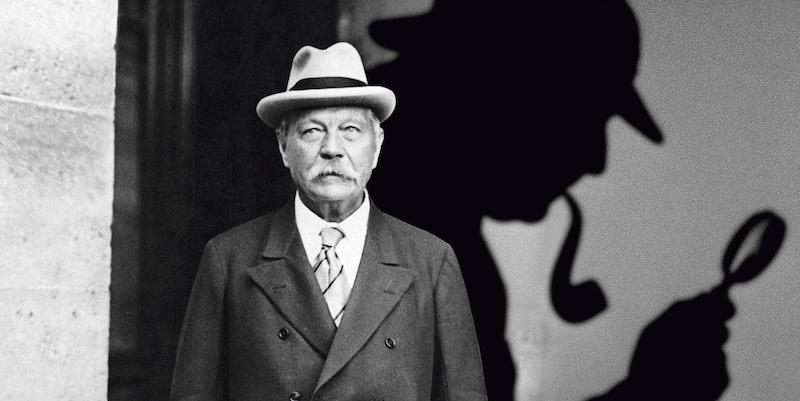

Arthur Conan Doyle wrote his first Sherlock Holmes installment, A Study in Scarlet, when he was only 27 years old. Written in just under three weeks, it is amazing to think that on how this work has endured and began a legacy, a series the likes of which may be unparalleled in fiction. A Study in Scarlet was popular and successful, and Conan Doyle was commissioned to write a sequel in less than a year. The next work, The Sign of the Four, was no less popular when it appeared in Lippincott’s Magazine. Amusingly enough, even early on in his Holmes works Conan Doyle felt contradictory emotions towards his most famous character. He wished to kill Holmes off after just a couple years, but was dissuaded (more like forbade) from doing so by his own mother! He raised the prices for his stories hoping to dissuade publishers from paying for them, but found that publishers were willing to pay exorbitant sums to keep the stories coming… consequently Conan Doyle accidentally became one of the best paid authors of all time. In all, Conan Doyle featured Sherlock Holmes (often against his will – public outcry was so great after Doyle had Holmes and Moriarty plunge off a cliff together that Holmes was forced to resurrect his famed detective in The Hound of the Baskervilles years later) in fifty-six short stories and four novels – a long and eventful life for a fictional character!

Arthur Conan Doyle wrote his first Sherlock Holmes installment, A Study in Scarlet, when he was only 27 years old. Written in just under three weeks, it is amazing to think that on how this work has endured and began a legacy, a series the likes of which may be unparalleled in fiction. A Study in Scarlet was popular and successful, and Conan Doyle was commissioned to write a sequel in less than a year. The next work, The Sign of the Four, was no less popular when it appeared in Lippincott’s Magazine. Amusingly enough, even early on in his Holmes works Conan Doyle felt contradictory emotions towards his most famous character. He wished to kill Holmes off after just a couple years, but was dissuaded (more like forbade) from doing so by his own mother! He raised the prices for his stories hoping to dissuade publishers from paying for them, but found that publishers were willing to pay exorbitant sums to keep the stories coming… consequently Conan Doyle accidentally became one of the best paid authors of all time. In all, Conan Doyle featured Sherlock Holmes (often against his will – public outcry was so great after Doyle had Holmes and Moriarty plunge off a cliff together that Holmes was forced to resurrect his famed detective in The Hound of the Baskervilles years later) in fifty-six short stories and four novels – a long and eventful life for a fictional character!

Starting with a short overview of the story (for the .000001% of you that have been living under a rock these past 160 years), we can come to look at the “expectations” housed within and see what we can decipher from the moral tale it holds. When young orphan Pip encounters an escaped criminal hiding in a churchyard one Christmas Eve, it gives him the fright of his life. The young boy is scared into thieving for the convict, and though the criminal is recaptured and clears Pip of suspicion, the incident colors Pip’s outlook on life. The young boy is sent to the house of the spinster and slightly mad Miss Havisham, to be used as entertainment for the lady and her adopted, aloof and haughty daughter Estella. Pip falls in love with Estella and visits them regularly until he is old enough to be taught a trade as an apprentice blacksmith. Four years into Pip’s apprenticeship, however, a lawyer arrives with news that Pip has anonymously been provided with enough money to become a gentleman. An astonished Pip heads to London to begin his new life, assuming Miss Havisham is to thank for his unexpected new windfall. Once in London the young Pip is introduced into some society, and makes new friends. His heart still belonging to Estella, he is ashamed of his previous life and expects his social advancement, new wealth and sudden social standing to sway her emotions towards him more favorably. It does not, Estella remains cold as ever, and Pip’s illusions are finally shattered when he realizes that his benefactor is not Miss Havisham at all, but the escaped convict Magwitch whom he helped in the churchyard all those years before. Through many mishaps and misfortunes, Pip and his friends attempt to help Magwitch escape England (which is ultimately unsuccessful), where he had returned to simply to make himself known to Pip. Pip learns valuable lessons throughout the story – interestingly not necessarily from those with money and social standing, but more often than not from those in his own class. The story has a kind ending, with Pip and an altered, warmer Estella walking hand in hand over a decade after her initial rejection of him (though Dickens originally planned a more likely, yet more disheartening end to the story and was convinced by Edward Bulwer-Lytton to change it).

Starting with a short overview of the story (for the .000001% of you that have been living under a rock these past 160 years), we can come to look at the “expectations” housed within and see what we can decipher from the moral tale it holds. When young orphan Pip encounters an escaped criminal hiding in a churchyard one Christmas Eve, it gives him the fright of his life. The young boy is scared into thieving for the convict, and though the criminal is recaptured and clears Pip of suspicion, the incident colors Pip’s outlook on life. The young boy is sent to the house of the spinster and slightly mad Miss Havisham, to be used as entertainment for the lady and her adopted, aloof and haughty daughter Estella. Pip falls in love with Estella and visits them regularly until he is old enough to be taught a trade as an apprentice blacksmith. Four years into Pip’s apprenticeship, however, a lawyer arrives with news that Pip has anonymously been provided with enough money to become a gentleman. An astonished Pip heads to London to begin his new life, assuming Miss Havisham is to thank for his unexpected new windfall. Once in London the young Pip is introduced into some society, and makes new friends. His heart still belonging to Estella, he is ashamed of his previous life and expects his social advancement, new wealth and sudden social standing to sway her emotions towards him more favorably. It does not, Estella remains cold as ever, and Pip’s illusions are finally shattered when he realizes that his benefactor is not Miss Havisham at all, but the escaped convict Magwitch whom he helped in the churchyard all those years before. Through many mishaps and misfortunes, Pip and his friends attempt to help Magwitch escape England (which is ultimately unsuccessful), where he had returned to simply to make himself known to Pip. Pip learns valuable lessons throughout the story – interestingly not necessarily from those with money and social standing, but more often than not from those in his own class. The story has a kind ending, with Pip and an altered, warmer Estella walking hand in hand over a decade after her initial rejection of him (though Dickens originally planned a more likely, yet more disheartening end to the story and was convinced by Edward Bulwer-Lytton to change it).