Tag Archives: rare books

A Brief History of Broadsides

“Broadsides are the most legitimate representatives of the most ephemeral literature, the least likely to escape destruction, and yet they are the most vivid exhibitors of the manners, arts, and daily life, of communities and nations. They imply a vast deal more than they literally express, and disclose visions of interior conditions of society, such as cannot be found in formal narratives.”

-Samuel F Haven

Samuel F Haven, former librarian for the American Antiquarian Society, presided over one of the largest collections of broadsides in the world. Historians and rare book collectors alike cherish broadsides because they offer snapshots of moments in time, helping us to understand the zeitgeist of that era. Broadsides make ideal complements to a rare book collection, granting the collection greater depth and context.

What a Broadside Is (and Isn’t)

Broadsides are single-sheet documents that are printed on only one side. They’re sometimes also called broadsheets. They’re different from handbills, which are smaller and printed on both sides. Broadsides should also not be confused with leaflets or booklets, which are folded from a single sheet of paper. The size of broadsides varies greatly, but they are generally smaller than posters and billboards.

Early broadsides didn’t include illustrations. They were simple documents printed in black ink. As printing processes got more sophisticated over time, the broadside also evolved. They began to include stock illustrations done from copper or wood engravings and eventually bore more intricate and relevant illustrations.

The Emergence and Decline of Broadsides

In Europe, broadsides came into use almost as soon as the printing press was invented. They first appeared in the United States during the seventeenth century, which the technology of moveable type and the printing press finally made its way to the colonies. For centuries, the broadside was the preferred format for delivering public announcements. They were also a cost effective way to distribute poetry, songs, and satire.

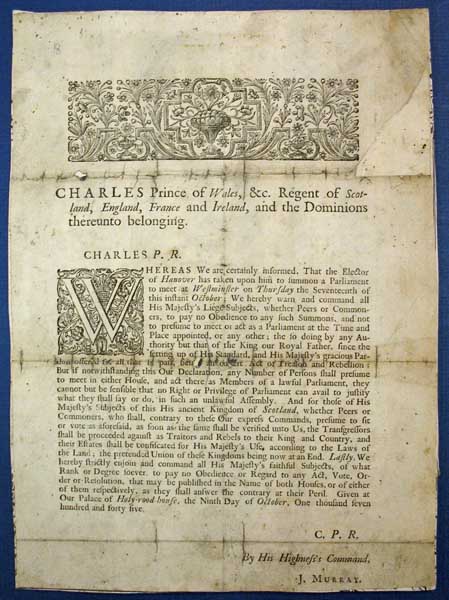

Bonnie Prince Charlie declares the illegitimacy of Parliament and calls all its attendees traitors. A fantastic artifact from the Jacobite rebellion.

Perhaps the most famous broadside in the United States is the broadside version of the Declaration of Independence published by John Durham on July 4 and 5, 1776. Thanks to this document, news of the declaration swept through the colonies. The John Durham broadside is a perfect example of how these artifacts can encapsulate a pivotal moment in history. Only a few decades earlier, Prince Charles of Wales had used a broadside to make a truly shocking announcement. He declared Parliament illegitimate and branded its participants as traitors. The broadside captures the heat of the Jacobite rebellion.

Before the end of the nineteenth century, broadsides had begun to fall into disuse. They’d been replaced by newspapers and radio for delivering news. Posters and billboards had replaced broadsides as advertisements. Today the occasional fine press artist produces a broadside, but the form has been rendered obsolete by technology.

Preserving and Collecting Broadsides

Broadsides fall into the category of ephemera because they weren’t made to last long. They were intended for quick consumption and therefore were often printed on cheap paper. Few people thought to keep broadsides, and the ones that did get saved are often in less than ideal condition. They may have folds and rips, or they may have been poorly repaired using the wrong materials. To protect broadsides from further damage, it’s important to protect them with a mylar sheath. Your broadsides can then be stored flat in a climate controlled environment.

The broadside edition of Macdonald’s “A Song for Chistmas” is incredibly rare. This is an inscribed presentation copy.

Meanwhile the ephemeral nature of broadsides is what makes them so valuable to rare book collectors. Some people actually specialize in broadsides. But the avid collector may supplement works by a favorite author with related broadsides. For example, a collector of George Macdonald would be interested in the broadside edition of Macdonald’s poem “A Song for Christmas.” Published around 1887, the broadside is the first appearance of the poem. It’s not published again until the 1890’s, when it appears in a collected volume. Macdonald’s “A Song for Christmas” broadside is now extremely rare; OCLC and KVK document only one other copy, at the Library of Scotland.

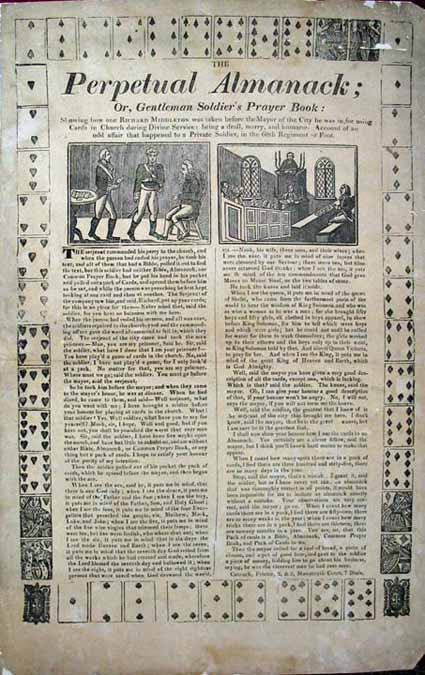

Chatto referred to this very broadside in his “Facts and Speculations on the Origin and History of Playing Cards”

Sometimes broadsides even served as sources for authors. William Andrew Chatto wrote about leisurely pursuits such as fly-fishing, smoking, and playing cards. In his 1848 Facts and Speculations on the Origin and History of Playing Cards, Chatto cites a Catnatch broadside called “The Perpetual Almanack; or, Gentleman Soldier’s Prayer Book.” The broadside tells the tale of Richard Middleton, who was taken before the mayor for using cards during a church service. Chatto notes that his own cards have been a “moral monitor and help to devotion.”

As your rare book collection progresses, incorporating broadsides is an excellent step to broaden the scope of the collection. What was the first broadside in your collection? And why did it appeal to you?

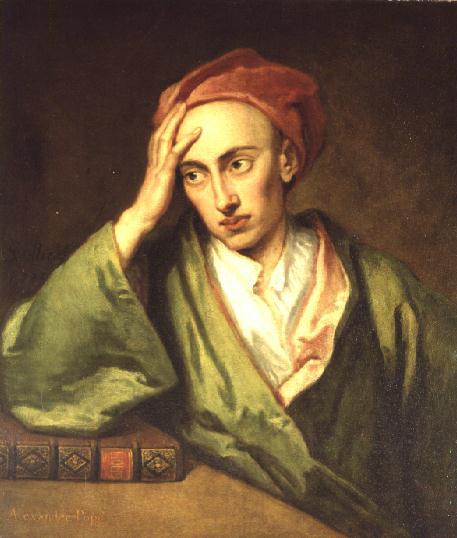

Alexander Pope’s Legacy of Satire and Scholarship

On May 21, 1688 Alexander Pope was born to Alexander and Edith Pope. Despite all odds, Pope would blossom into a preeminent British poet of the eighteenth century. Pope left behind an ingenious translation of Homer’s Iliad, along with a robust body of poetry and criticism. Though history has not always been kind to Pope, he’s recognized as a truly masterful poet whose influence can still be felt.

Challenges of Anti-Catholicism and Illness

Pope’s parents were recent converts to Catholicism, and they chose an inopportune time to leave the Church of England; anti-Catholic sentiments ran high, and the Test Acts seriously limited the rights and opportunities of Catholics. The family was forced to move out of London to Binfield. Catholics were also forbidden to attend public schools, so Pope was mostly educated at home by his aunt. For a few years he attended a Catholic school in London, but he taught himself French, Italian, Latin, and Greek. Pope had discovered Homer by the time he was six years old.

When Pope was 12 years old, he published his earliest extant work, Ode to Solitude. That same year, he developed the first symptoms of a disease that would cripple him for the rest of his life. Now largely accepted to be Pott’s disease, a form of tuberculosis, the illness stunted Pope’s growth and caused severe deformation of his spine. He never grew over four-and-a-half feet, and he remained frail and asthmatic throughout his life. Pope’s size and appearance would later make easy fodder for his detractors, who called him the “hump-backed toad.”

A Rapid Rise to Fame

In 1710, Pope’s Pastorals appeared in Jacob Tonson’s Poetical Miscellanies. Pope claims, however, that he wrote the poem earlier, when he was only 16 years old. The following year saw Essays on Criticism published anonymously–but everyone knew it was Pope. The work highlighted Pope’s mastery of (and preference for) the heroic couplet. It also attracted the attention of more established poets Jonathan Swift and John Gay. Together, the three poets would go on to found the Scriblerus Club. Its purpose: to satirize ignorance and poor taste. Scriblerus, a precursor to Pope’s Dunciad, features the inept character Martinus Scriblerus, who embodies incompetent criticism and scholarship.

When Pope published The Rape of the Lock in 1712, he cemented his position as an outstanding poet of the time. The poem pokes fun at a real-life squabble between two prominent Catholic families over the theft of a young woman’s lock of hair. Pope was now part of a circle of elite writers that included not only Swift and Gay, but also Joseph Addison, Thomas Parnell, and John Arbuthnot. These writers were all overtly Tory, but Pope’s true political standing was never clear.

An Authorial Living Thanks to Homer

Swift consistently encouraged Pope to undertake a translation of Homer’s Iliad. The project was a huge risk; Pope was only 25 at the time and still had anti-Catholic laws working against him. He didn’t have a private patronage as many other writers had. Thus Swift undertook the work of building a subscription list for Pope’s translation. Swift’s efforts paid off. He built an impressive list in both length and prestige. Thanks to the subscriptions, Pope did what few other authors of the time could: he actually made a comfortable living as a writer.

Pope published The Iliad in six volumes, writing 30 to 50 verses per day. He wrote his drafts on the backs of letters to him and to his mother. His first volume came out in 1715, at the same time that Thomas Tickell published a rival edition. Pope’s was accepted as quite superior, even though it bears little resemblance to the original Greek text. Samuel Johnson even declared it the best translation of all time, in any language. Pope used the same subscription model when he tackled The Odyssey.

When Pope’s father passed away in 1719, Pope moved back to the family estate at Twickenham. He used the profits from The Iliad to construct an incredible grotto on the property. It had a camera obscura and other enticing features. The grotto still stands today, though it’s not often open to the public.

Pope Sparks Controversy

Pope decided to undertake his own adaptation of Shakespeare. It didn’t meet the same acceptance as his adaptations of Homer because Pope “corrected” the Bard’s verse. He also changed the text in many places, but left earlier corruptions untouched. Scholar and critic Lewis Theobald excoriated Pope for the work. Pope fought back, making Theobald the protagonist of the Dunciad.

Pope’s Dunciad sparked an incredibly hostile response–so hostile that Pope would leave his house only with two loaded pistols in his pockets. William Broome, who had collaborated with Pope on The Odyssey, also found himself a target in the Dunciad. He was surprised that Pope didn’t receive more vituperation: “I wonder he’s not been thrashed, but his littleness is his protection; no man shoots a wren.”

In 1735, a year after Pope published Essay on Man, Pope placed himself at the center of another controversy. An unauthorized version of Pope’s correspondence appeared, the work of notoriously unscrupulous publisher Edmund Curll. Collected correspondence was relatively rare at the time, so the publication caused quite a furor. In reality, Pope had edited his own letters and delivered them to Curll in secret.

Pope’s health began to suffer in 1738. He turned his attention to revising the Dunciad, this time with British poet laureate Colly Cibber as the protagonist. Cibber was widely thought to lack talent and to have used political connections to get the position of laureate.

Reception of Pope

Pope’s work remained influential until the nineteenth century. The Romantics saw Homer as a bard, a poet close to nature. Pope’s imposition of rigid structure on the blind poet’s work was considered quite the opposite–unnatural, contrived. Furthermore, the Romantics saw little merit in Pope’s acerbic wit and biting criticism. Later, however, writers and scholars recognized that Homer’s Greece was a place of strict adherence to customs about sacrifice, prayer, war, and hospitality. The strict prosody of Pope’s adaptation reflected the codified social customs of Greece. Pope is now esteemed as one of the great writers of his century.

The Man Behind the Beloved Freddy Series

George Orwell’s Animal Farm (1945) is synonymous with talking animals, but Orwell wasn’t the first to populate a novel with anti-establishmentarian, anthropomorphic animals. Walter R Brooks created the beloved Freddy the Pig and his friends on Bean Farm almost two decades earlier. Though Brooks’ Freddy books aren’t as overtly political as Orwell’s work, they do depict animals overcoming corrupt authority. Brooks had a rich, varied literary career that included not only the Freddy novels, but also numerous short stories, editorials, and literary reviews.

Brooks was born in Rome, New York on January 9, 1886. When he was four years old, his father passed away. His mother died eleven years later, and Walter was sent to Mohegan Lake Military Academy in Peekskill, New York. He stayed there from 1902 until 1904, where he moved in with his sister Elsie in Rochester. Elsie’s husband, Dr. William Perrin was a renowned homeopathic physician and a professor at the University of Rochester. Brooks took classes there for a few years, and in 1906 he went to New York City to study at the Homeopathic Medical College and Flower College. Brooks left New York City in 1908, returning to Rochester to marry Anne Shepherd.

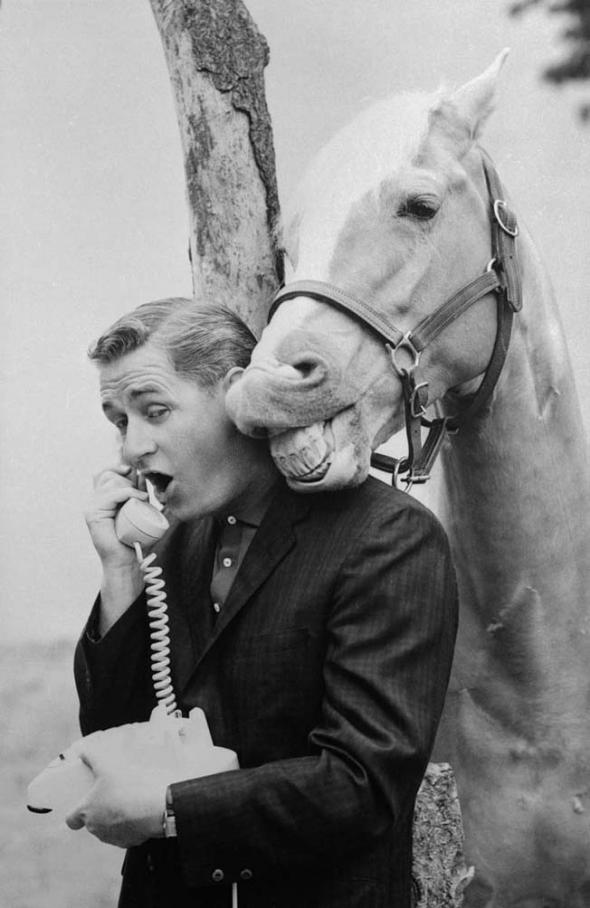

The year 1910 found Brooks in an entirely new field; he worked for Frank Du Noyer advertising agency in Utica. His tenure there proved short, however. In 1911, Brooks “retired.” It’s speculated that when his maiden aunts passed away, Brooks inherited a significant sum. He turned his attention to writing. Brooks was published for the first time in 1915, when his sonnet “Haunted” was printed in Century magazine. That same year, his short story “Harden’s Chance” appeared in Forum magazine. Two years later, Brooks joined the American Red Cross as a publicist. He continued writing short stories, however, and in 1934 began selling stories to Esquire. In total, Brooks published more than 100 short stories, 25 of which featured Ed the talking horse–the inspiration for the TV series “Mr. Ed.”

The year 1910 found Brooks in an entirely new field; he worked for Frank Du Noyer advertising agency in Utica. His tenure there proved short, however. In 1911, Brooks “retired.” It’s speculated that when his maiden aunts passed away, Brooks inherited a significant sum. He turned his attention to writing. Brooks was published for the first time in 1915, when his sonnet “Haunted” was printed in Century magazine. That same year, his short story “Harden’s Chance” appeared in Forum magazine. Two years later, Brooks joined the American Red Cross as a publicist. He continued writing short stories, however, and in 1934 began selling stories to Esquire. In total, Brooks published more than 100 short stories, 25 of which featured Ed the talking horse–the inspiration for the TV series “Mr. Ed.”

In 1927, Walter published the first Freddy book under the title To and Again (later, Freddy Goes to Florida). He would go on to write a total of 26 books featuring Freddy the Pig. Meanwhile, in 1928 Brooks embarked on a series of positions with various magazines. Until 1932, he was a columnist and book review editor for The Outlook and Independent. Through these positions, Brooks was among the first to discover Dashielle Hammett. Brooks went on to write for New Yorker, Fiction Parade, and Scribner’s Commentator.

The Freddy books were by far Brooks’ most popular, and they sold quite well. Set on the Bean Farm in upstate New York, they included both human and animal characters–and the humans never seemed too surprised that the animals could talk. Freddy isn’t a likely hero; he’s quite lazy and manages to accomplish anything only because it’s easier to keep going once he’s gotten started. The novels’ villains frequently represent some form of the Establishment, and the novels’ conflicts generally appeal to children’s sense of fairness and equality.

The Freddy books were by far Brooks’ most popular, and they sold quite well. Set on the Bean Farm in upstate New York, they included both human and animal characters–and the humans never seemed too surprised that the animals could talk. Freddy isn’t a likely hero; he’s quite lazy and manages to accomplish anything only because it’s easier to keep going once he’s gotten started. The novels’ villains frequently represent some form of the Establishment, and the novels’ conflicts generally appeal to children’s sense of fairness and equality.

Critics have likened the Freddy books to AA Milne’s Winnie the Pooh books and Kenneth Grahame’s Wind in the Willows. Despite their mass appeal, however, the Freddy books began going out of print in the 1960’s. Thanks to the urging of Friends of Freddy, Alfred A Knopf issued new paperback editions of eight titles in 1986 and 1987. They included an introduction by Brooks’ biographer, Michael Cart, and gleaned substantial praise from reviewers. Now the books are available from the Overlook Press.

Although Brooks’ works are no longer in the spotlight, they’re still much loved among a devoted circle of fans. Many collectors also love the Freddy series, not only because the books evoke their childhood, but also because the books have wonderfully attractive dust jackets and illustrations.

Rare Books a Mother Could Love

This Sunday the United States celebrates Mothers Day, and many of us are still searching for the perfect gift ideas. If your mother has a predilection for rare books, choose the perfect volume for her personal library.

Evoke Childhood Memories

Classic children’s books give Mom an opportunity to reminisce about her youth–and to share a piece of her childhood with future generations. Choose a title from a beloved series.

The Poppy Ott series by Leo Edwards (pseudonym for Edward Edson Lee) was published in the 1920’s and 1930’s. Though these books were primarily marketed for boys, plenty of girls fell in love with Poppy Ott and his penchant for stumbling into adventure.

The Poppy Ott series by Leo Edwards (pseudonym for Edward Edson Lee) was published in the 1920’s and 1930’s. Though these books were primarily marketed for boys, plenty of girls fell in love with Poppy Ott and his penchant for stumbling into adventure.

Palmer Cox’s Brownies series recounts the adventures of mischievous, fairy-like sprites in humorous verse. These books were already beloved classics by the turn of the 20th century and maintained their popularity long after.

Palmer Cox’s Brownies series recounts the adventures of mischievous, fairy-like sprites in humorous verse. These books were already beloved classics by the turn of the 20th century and maintained their popularity long after.

Mildred A Wirt wrote the perennially popular Nancy Drew series under the pen name Carolyn Keene. Nancy Drew and her friends always managed to find a mystery, and the series remains in print today.

Mildred A Wirt wrote the perennially popular Nancy Drew series under the pen name Carolyn Keene. Nancy Drew and her friends always managed to find a mystery, and the series remains in print today.

The Japanese Fairy Tales series, published in Tokyo in the 1890’s, offer a beautiful glimpse into the mores and stories of Japan. Bound in the “yamoto toji” style, the books are in french-fold format and printed on crepe paper.

The Japanese Fairy Tales series, published in Tokyo in the 1890’s, offer a beautiful glimpse into the mores and stories of Japan. Bound in the “yamoto toji” style, the books are in french-fold format and printed on crepe paper.

Bring Art to the Shelves

The right rare art book is both visually stunning and intellectually engaging. If your mother loves art–or beautiful objects–one of these rare items may be the ideal gift.

Lewis Lott produced his Collection of Beautiful Miniatures in the 1860’s. It includes faithful reproductions of 70 original miniature paintings, mostly from the 14th and 15th centuries.

Chang Dai-chien was one of the most renowned and prolific Chinese artists of the 20th century. This collection, published by the East Society, includes 130 reproductions of his paintings since 1944.

Chang Dai-chien was one of the most renowned and prolific Chinese artists of the 20th century. This collection, published by the East Society, includes 130 reproductions of his paintings since 1944.

Frances Hebert’s original watercolor of Santa Catalina Island’s Avalon Bay in California depicts an elevated view of the bay, from the hills to the South-Southeast. It’s matted and mounted in a gilded wooden frame.

Frances Hebert’s original watercolor of Santa Catalina Island’s Avalon Bay in California depicts an elevated view of the bay, from the hills to the South-Southeast. It’s matted and mounted in a gilded wooden frame.

Share a New Perspective on a Favorite Author

Some legendary authors, like Walt Whitman, are famous for leaving behind copiously annotated manuscripts. These documents provide a more dynamic view of the author’s work, but they’re not the only way to offer a fresh perspective on a beloved writer.

Louisa May Alcott is famous for Little Women, but fewer people know that she served in a hospital. Hospital Sketches and Camp and Fireside Stories includes six sketches about Alcott’s time working in the hospital.

Louisa May Alcott is famous for Little Women, but fewer people know that she served in a hospital. Hospital Sketches and Camp and Fireside Stories includes six sketches about Alcott’s time working in the hospital.

Anais Nin’s first book was DH Lawrence: An Unprofessional Study. The work gives us insight on both Lawrence and Nin, an unusual combination and an interesting item for collectors of either author.

Poet, artist, and dancer Sven Berlin was a member of the St. Ives art colony–until a falling out with other writers over his novel The Dark Monarch. This original draft of Berlin’s Amergin the White Stag contains magnificent pen and ink drawings to be used as illustrations, along with Berlin’s notes to the typist, chapter notes, etc. It’s truly an intriguing manuscript.

Poet, artist, and dancer Sven Berlin was a member of the St. Ives art colony–until a falling out with other writers over his novel The Dark Monarch. This original draft of Berlin’s Amergin the White Stag contains magnificent pen and ink drawings to be used as illustrations, along with Berlin’s notes to the typist, chapter notes, etc. It’s truly an intriguing manuscript.

Even if none of the above suits your mother, all of us here at Tavistock Books wish all mothers the very best of days! We thank you for visiting our blog, and hope you enjoy your day!

The Millerites and the Great Disappointment

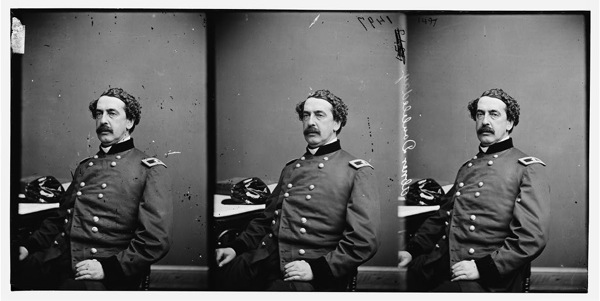

William Miller

The Seventh-day Adventist Church rose from what most would consider an epic failure. William Miller predicted the return of Christ–inaccurately, and his followers broke into multiple sects, of which the Seventh-day Adventist Church was one. The literature and ephemera of the Millerite community offers a fascinating look at religion and spirituality in the mid-1800’s.

A Brief History of Millerism

The early 1800’s saw a resurgence in millenarianism, the belief that a major event or movement would cause a drastic transformation in society. Specifically, millenarianists believed in the prophecy of Revelation, which predicts that God’s kingdom on Earth will last 1,000 years after Jesus’ return. Thus, the ground was fertile for the theology of William Miller, for whom Millerism is named.

Miller started out as a farmer in upstate New York. He was also a lay preacher in the Baptist church. He embarked on an exhaustive study of the prophecies of Daniel. A subscriber to the year-day method of prophetic interpretation, Miller believed that a “day” in the Scripture represented a year of real time–meaning that we could predict the exact date of Jesus’ return. By September of 1822, Miller had published his conclusions in a twenty-point document, though he shared the document with very few people.

Miller began sharing his ideas more openly among his inner circle. Initially, he met with disinterest. He said, “To my astonishment, I found very few who listened with any interest. Occasionally one would see the force of the evidence, but the great majority passed it it by as an idle tale. But when Miller began lecturing publicly in 1831, he began to gain a following. The following year, he submitted 16 articles to the Baptist paper Vermont Telegraph. Soon he was unable to personally address all the correspondence and speaking requests he received as a result of the articles.

To remedy that problem, Miller published a 64-page tract that summarized his predictions. At this point, he still had not specified a date for Jesus’ return; instead, he suggested that the Advent would occur in 1843 or 1844. As the years passed, Miller gained more and more attention–in large part due to Millerite publications. Miller’s campaign got a significant bump when Joshua Vaughan Himes, a preacher and publisher, began printing the fortnightly paper Signs of the Times. The first issue was published on February 28, 1840, and the periodical is still published by the Seventh-day Adventist Church.

As Miller’s ideas gained ground, numerous items in the Millerite tradition were published. One such item was a broadside called “The Battle of the Great Day.” Based on Revelation 16: 12-21, the broadside was published by prolific preacher Thomas Williams around 1838. Though several works by Williams are recorded in UMI’s “Millerites and Early Adventists,” this item is not. The OCLC lists only one other institutional holding, at Brown University.

By 1843, there were at least 48 Millerite publications. Meanwhile, Miller had narrowed down his dates at the urging of his followers. Now he offered a year-long window: March 21, 1843 to March 21, 1844. When March 21, 1844 came and went without incident, most Millerites maintained their faith. They briefly adopted a new end date of April 18, 1844, based on the Karaite calendar rather than the Rabbinic one. When that date also passed, they believed they’d entered “tarrying time,” a period of waiting mentioned in both the books of Daniel and Habakkuk. This idea sustained them through July of 1844.

In August of that year, Samuel S. Snow presented a new theory at a meeting in Exeter, New Hampshire. Known as the “seventh-month message,” Snow’s prediction was still based on the 2300 prophecy of Daniel, which stated that Jesus’ return would occur on the tenth day of the seventh month. Again using the Karaite calendar, Snow calculated that October 22, 1844 as the date of the Advent. When Snow, too, proved incorrect and nothing happened on October 22, the Millerites experienced what has since been called the Great Disappointment. The movement soon fell apart as the Millerites struggled to reconcile their beliefs with reality. Multiple sects emerged, one of which was the Seventh-day Adventist Church.

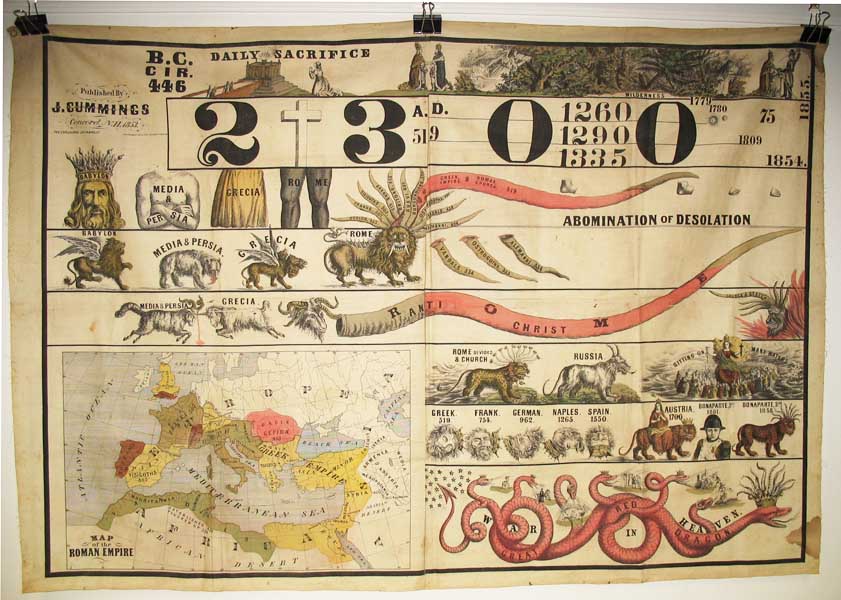

The Cartography of Faith

Many Millerites turned to Scripture, hoping to find an error in Miller and Snow’s calculations. One of these was Jonathan Cummings, a farmer who’d become a preacher in 1830. Cummings wrote a lengthy letter to Himes, which was published in the Advent Herald on November 2, 1852. He offered new insight on the chronology. Cummings also produced a fascinating banner-size chart (pictured below and recently sold) that identifies 1854 as the year for the Second Coming. He also printed An Explanation of the Prophetic Chart and Application of the Truth to accompany the banner.

While Cummings was not the only Millerite to recalculate the date of the Second Coming, his unusual chart is featured and discussed in both Cartographies of Time and the Encyclopedia of American Folk Art. The OCLC records only five institutional holdings of the banner, making it an exceptionally rare publication to be found on today’s market.

The Millerite movement certainly fueled the publication of many fascinating rare books and ephemera. Tavistock Books is always interested in acquiring items like Cummings’ chart and Williams’ broadside. Please contact us if you would like more information about what we’re looking for, or if you have an item of interest.

Happy Birthday, William Shakespeare!

Today we celebrate the birthday of the world’s most famous playwright and poet, William Shakespeare. While he’s best known for works like Romeo and Juliet, Midsummer Night’s Dream, and Macbeth, Shakespeare produced an incredibly diverse body of work that includes many overlooked pieces. Scholars have approached Shakespeare from countless angles. Both Shakespeare’s works and Shakespearean scholarship have fascinated rare book collectors for centuries, and the items below offer an interesting glimpse into Shakespeare’s genius.

Cymbeline

Cymbeline: A Tragedy is based on part of the Historia Regum Britanniae of Geoffrey of Monmouth, which details the life of British monarch Cunobelinus. Shakespeare, of course, weaves in multiple sub-plots and adapts the story to make it more dramatic and engaging. The date of Cymbeline’s authorship isn’t certain, though it was certainly performed as early as 1611. It used to be one of Shakespeare’s most highly regarded plays but has fallen out of favor in the past few centuries. Multiple scholars have asserted that Shakespeare worked with a collaborator to write Cymbeline; several passages sound patently “un-Shakespearean.” Our 1734 edition of Cymbeline, printed for J. Tonson, includes a frontis by Guernier and a title page printer’s ornament of a bust of Shakespeare.

The History of Sir John Oldcastle

Originally published anonymously in 1600, The History of Sir John Oldcastle, the Good Lord Cobham is an extremely rare Shakespearean work. The second edition (1619) attributed the work to Shakespeare. Sir John Oldcastle was a real person who was hanged and burned for heresy and treason in 1417. Oldcastle is incorporated as a minor character in Famous Victories of Henry V, which was undoubtedly a source for Shakespeare’s Henry IV and Henry V. Earlier versions of Henry IV use “Oldcastle,” rather than “Falstaff,” and it’s thought that Shakespeare changed the name to avoid offending the Cobham family. According to Jaggard, who cites Henslowe’s diary, authorship of this history was a joint effort of Drayton, Munday, Wilson, and Hathway. Other scholars even assert that these four actually wrote The History of Sir John Oldham as a response to Shakespeare’s Henry IV. Regardless of its authorship, the piece is exceptionally scarce on the commercial market.

Shakespeare Head Press Booklets

In 1904, Elizabethan scholar AH Bullen established the Shakespeare Head Press in Stratford-upon-Avon. His goal: to produce an exceptional version of Shakespeare’s works. Bullen administered the private press until his death in 1927; it was then acquired by a partnership that included Oxford bookseller Basil Blackwell. The press has become quite famous in its own right. This collection of Shakespeare Head Press booklets represents early works from the press and includes “Ancient Carols” (2nd ed); “Festive Songs for Christmas” (2nd ed); “Shakespeare’s Songs”; “The Nutbrown Maid”; “A Lover’s Complaint”; and “The Phoenix and Turtle.”

The Great Cryptogram

The full title of this work is The Great Cryptogram: Francis Bacon’s Cipherin the So-Called Shakespeare Plays (1888). Its author, Ignatius Donnelly, began his career as a Minnesota farmer and went on to be a Congressman for the state. He was active in the formation of the Populist Party. Later, Donnelly turned his efforts to authorship, and here he argues that philosopher Francis Bacon is the real author of Shakespeare’s works. Donnelly’s argument was a popular one in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Donnelly traveled to England to arrange an English publication of the work. He spoke at Oxford Union, and his thesis “Resolved, that the works of William Shakespeare were composed by Francis Bacon,” was defeated by vote. Donnelly found himself publicly discredited, and the book was a failure.

Assorted Scholarship

The breadth, depth, and impact of Shakespeare’s works have resulted in an immense body of Shakespearean scholarship. You’ll find works that explore Shakespeare’s connection to Charles Dickens or Shakespeare and Milton, along with more obscure items like Christopher Morley’s lectures on Shakespeare and Hawaii. These items are often relatively affordable, making them both interesting and accessible for rare book collectors. They also add context and texture to a Shakespeare collection.

George Steevens: Bibliophile, Scholar, and Prankster

Perhaps best remembered for his exceptional contributions to the study of Shakespeare, George Steevens was also an incredible collector of books. His enthusiasm for Elizabethan literature led him to build an amazing collection, which also included a number of William Hogarth prints. After Steevens’ death in 1800, his library was sold. A significant portion went to the British Museum. But among his contemporaries, George was equally well known for his literary pranks–which did little to endear him to his colleagues.

Shakespeare Scholarship

Steevens’ first published works on Shakespeare were 49 notes to Samuel Johnson’s 1765 edition of Shakespeare’s works. He strongly believed in preserving the quarto editions of Shakespeare, and soon published Twenty of the plays of Shakespeare, being the whole number printed in quarto during his life-time, or before the restoration, collated where there were different copies, and published from the originals. Johnson was so impressed with Steevens’ work, he suggested that Steevens undertake the entirety of Shakespeare’s works.

Samuel Johnson

That edition, The plays of Will Shakespeare (1773), was ten volumes long and took six years to publish. Though Johnson had contributed to the book only minimally, Steevens lionized his involvement to bolster sales. The edition was received quite well, though later it was discovered that Steevens had borrowed generously from Edward Capelli’s 1768 edition. Steevens and Isaac Reed published an updated edition in 1778. Reed undertook a third edition in 1785, but Steevens, who considered himself a “dowager” editor by this time, had little to do with the project. He resumed involvement only because of his resentment for rival editor Edmond Malone.

Steevens’ Hoaxes and Exploits

For all Steevens’ scholarship, he earned the nickname “Puck of Commentators” for his mischievous pranks. This was certainly a gentle assessment; Steevens executed some exceptional pranks. For his first (mis)deed, Steevens forged a letter from George Peele, recounting his meeting with Shakespeare and other dramatists at the Globe Theatre. Everyone accepted the letter as genuine, and it even appeared in Dr. John Berkenhout’s Biographia litteraria (1777).

Later Steevens decided to exact revenge on Richard Gough, a well known antiquarian against whom Steevens held a grudge. Gough refused to trade his Hogarth plates for some of Steevens’ rare books. Steevens had a large marble block engraved with an Anglo-Saxon inscription and the name “Hardecanute.” The tombstone was displayed in a Southwark shop, and Steevens circulated the story that the headstone had been discovered in Kennington. The faux artifact gleaned a write-up in Gentlemen’s Magazine (1790), and it was Steevens himself who revealed the forgery.

Even accomplished biologist and botanist Erasmus Darwin was taken in by Steevens’ ploys. In the December 1783 issue of London Magazine, Steevens published a description of the invented upas tree of Java, which could kill all other life within 15 to 18 miles. He based his account on the reports of an invented Dutch traveler. Darwin accepted the account and included it in his 1789 Loves of the Plants.

The Other Side of the Coin

Though Steevens obviously loved a good prank, he also helped to expose some of the most notorious forgers of his era. When Samuel Ireland announced that his son William Ireland had discovered a treasure trove of Shakespeare manuscripts. Steevens was quick to criticize the “discovery” and declare the Ireland editions to be forgeries. He also played an important part in exposing the Chatterton-Rowley forgeries.

Meanwhile Steevens was also known for his generosity–sometimes helping the family members of his own rivals. He assisted the family of author Oliver Goldsmith and many others. Ultimately these acts mitigated Steevens’ peers’ evaluation of him. Now he’s remembered not for these hoaxes, but for his scholarship and bibliography.

The Rare Books of Baseball

This weekend kicks of the beginning of the 2013 Major League Baseball season. While the precise origins of the game remain dubious, the sport has gained a sure place as the most popular sport of focus among rare book collectors.

A Legendary Rivalry

Henry Chadwick (1824-1908) was a British-born journalist. A true baseball enthusiast, Chadwick launched one of the first newspaper columns devoted to baseball. He was also among the first to record baseball statistics as a means to evaluate individual players’ performance. In 1903, Chadwick wrote an article suggesting that baseball was a form of an English game called rounders. The game had similar rules and equipment, so the guess seemed plausible enough.

Enter Albert Spalding (1850-1915). A great pitcher from the 1870’s, Spalding was one of baseball’s greatest advocates. He owned the Chicago White Stockings and the National League of Professional Ball Clubs. In 1911, Spalding launched a massive campaign to make baseball the national pastime. He believed that baseball was a quintessentially American game–and was invented by Americans. Thus he vociferously disagreed with Chadwick’s assertion that baseball had British origins.

To settle the disagreement, Spalding appointed a committee whose mission was to uncover the origins of baseball. He selected Abraham Mills as the chairman. Mills was the National League’s president from 1882 to 1884. The task force, nicknamed the “Mills Commission,” ruled on December 30, 1907 that Abner Doubleday had invented baseball. Immediately a myth was born.

The Doubleday Myth

The Mills Commission based their ruling almost entirely on the testimony of one man: 71-year-old Abner Graves, a mining engineer who lived in Denver, Colorado. Graves responded to a “call for people who had knowledge of the game,” placed in Akron, Ohio’s Beacon Journal by Spalding. Graves claimed that he’d seen Doubleday draw a diagram of a baseball field back in 1839, during a schoolboy’s game. Graves sent his account to the Beacon Journal, which printed it with the headline “Abner Doubleday Invented Baseball.”

US Army general and Civil War hero Abner Doubleday was spuriously credited with creating baseball thanks to the Mills Commission.

Meanwhile Doubleday himself never claimed that he invented the sport. A US Army general and Civil War hero, Doubleday never once mentioned baseball in his extensive diaries. By the time the Mills Commission declared Doubleday the inventor of baseball, he’d already passed away. But that didn’t stop the myth from taking on a life of its own. Soon, Doubleday was even credited with introducing baseball to Mexico during the Mexican-American War.

Flaws in the Doubleday Myth

Unfortunately the Mills committee overlooked some critical information. First, Graves wasn’t the most reliable witness. He’d been only five years old in 1839 when he supposedly saw Doubleday diagram the baseball field. But the greatest flaw in Graves’ account was that Doubleday was not even in Cooperstown, New York in 1839.

Clearly Doubleday hadn’t invented baseball, but who had? America longed for an answer. In 1953, Congress named Andrew Cartwright the inventor of baseball, definitively debunking the Doubleday myth. Cartwright, a volunteer firefighter, had been a founding member of the New York Knickerbockers (est September 23, 1845). He’d been instrumental in making baseball more of a gentlemen’s sport. But modern scholars of baseball have also dismissed Cartwright as baseball’s inventor.

The New York Knickerbockers were the first organized baseball team. In 1953, Congress declared founding member Andrew Cartwright the inventor of baseball.

Historian and antiquarian David Block is the leading scholar on the history of baseball. His 2005 book, Baseball before We Knew It: A Search for the Roots of the Game, outlines the earliest mentions and illustrations of baseball in literature. The first known appearance of “base-ball” in print occurred in the 1744 edition of A Little Pretty Pocket-Book. And the first-known rules of baseball were printed in Spiele zur Erholung (1796). The German book that summarizes the rules of a game called “Ball mit Freystaten (oder das englische Base-ball),” which translates as “ball with free station (or English base-ball). Block illustrates the similarities between baseball and trapper ball He also notes that the first written account of rounders in England was in The Boy’s Own Book (1828).

Thus, neither Chadwick nor Spalding (nor the 1953 American Congress) was correct about baseball’s origins. The game had already existed for nearly a century before Doubleday, Cartwright, or any of their relative contemporaries could have “invented” it.

Collecting Rare Baseball Books

Baseball is by far the most popular game among collectors who specialize in a sport. This is due, in large part, to the mysterious origins of the sport. But there are also plenty of niches for collectors to focus on, from baseball’s early history, to regional leagues or specific teams, to baseball fiction.

Henry Chadwick, the sports writer who had questioned baseball’s origins, played a significant role in nationalizing the rules of baseball. He wrote Beadle’s Dime Base-Ball Player most years, from 1860 to 1881. The guide included not only rules for the game itself, but also guidelines for establishing baseball clubs and game statistics from the previous year. These guides were ubiquitous at the time, helping to spread interest in the game and normalize rules. But Chadwick’s guides have become exceptionally scarce, and they’re prized among collectors who specialize in baseball.

One of the earlier references to “base-ball” as a children’s game comes from Juvenile Pastimes; Or Girls’ and Boys’ Book of Sports (1849). References to the sport at this time are particularly uncommon. One of the 17 woodcuts in this book depicts two boys playing “base-ball,” making it a relatively early pictorial depiction of the game.

One of the earlier references to “base-ball” as a children’s game comes from Juvenile Pastimes; Or Girls’ and Boys’ Book of Sports (1849). References to the sport at this time are particularly uncommon. One of the 17 woodcuts in this book depicts two boys playing “base-ball,” making it a relatively early pictorial depiction of the game.

Baseball fiction has long been favored among collectors. Earlier baseball fiction was often published in serial form, though novels soon gained steam. One especially collectible title is Freddy and the Baseball Team from Mars (1955) by Walter R Brooks. The Freddy series itself is beloved among many collectors of modern first editions, as well.

Ephemera also remains attractive, especially to collectors who focus on individual teams. One particularly interesting piece of ephemera comes in the form of a poem by Barry Gifford. An avid Cubs fan, Gifford published “The Giants Are Going to Win the Pennant” on a Madrugada broadside. He compares the poet Jack Spicer to Ted Williams, one of the greatest baseball players of all time, whose “hits are in/the record books/waiting to be broken.”

As Americans’ love of baseball remains strong and the game continues to evolve, collectors of rare baseball books will undoubtedly have plenty of opportunities to expand their collections.

Don’t Miss the Sacramento Antiquarian Book Fair

This Saturday we’ll be taking Tavistock Books on the road for the Sacramento Antiquarian Book Fair. One of the best regional book fairs, the show features booths from 60 vendors. This Sacramento book fair has gained an excellent reputation in the community, and visitors will find an incredibly variety of items, including many that cannot be found anywhere online.

Sacramento Antiquarian Book Fair

March 23rd, 2013: 9:45 AM to 5 PM

September 14, 2013: 9:45 AM to 5 PM

Scottish Rite Temple, 651 H Street, Sacramento 95819

This fair is unique because it draws such a strong crowd year after year. Fair manager Jim Kay has worked hard to make the event accessible–and memorable–for visitors. For about 20 years now, the fair has been at the Scottish Rites Temple, an ideal location because it’s spacious and offers plenty of free parking. Meanwhile, visitors find a wide variety of unique items. “Our dealers bring items that are unique, and most of them bring items that you simply can’t find on the internet,” says Kay.

Visitors will also be able to get free appraisals on their own antiquarian books, which is always a popular service. Kay, who’s been a book dealer himself for many years, conducts the appraisals. If you’ve always wondered what your books are worth, now’s the time to find out!

The Sacramento Antiquarian Book Fair draws crowds from all backgrounds, from beginners to serious rare book collectors. “Fair offerings run the general gamut, from $5 to $20,000 books. You’ll find collectibles and relatively modern authors, but someone looking for a very rare John Steinbeck would also likely find it if it’s available. There are postcards, original art pieces, diaries of people from the Gold Rush, and more,” says Kay. He also noted that collectors would find plenty of graphic items and ephemera, such as movie posters from the 1920’s and even original paintings.

You’ll find us at the fair with a spectacular collection of items from our inventory. If you’d like to see a particular item, please let us know and we’ll do our best to bring it for you.