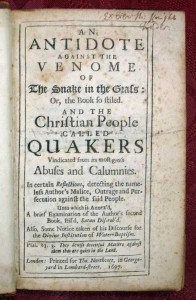

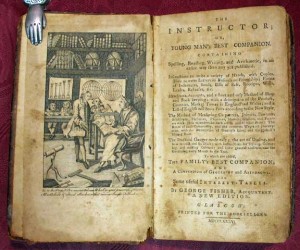

We’ve long been fascinated with the exploits of criminals, so much so that an entire genre of literature has blossomed out of our curiosity. In the eighteenth century, a staple of true-crime literature was the confession, in which a convicted criminal shared his life story, detailed the sordid details of his crimes, and repented of his sins. These stories were often published as broadsides or pamphlets—and distributed to the audience who gathered to witness the criminal’s execution. Longer accounts sometimes appeared after the fact.

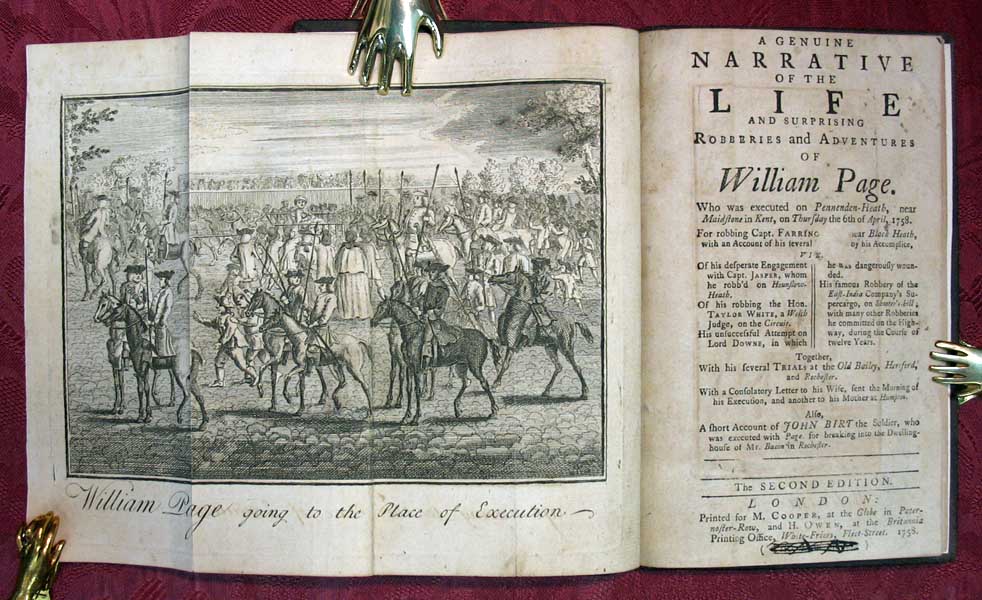

One criminal who shared his story has an interesting connection to none other than Henry Fielding. Also a magistrate, Fielding sentenced famous highwayman William Page to death for his crimes. Page was hanged in 1758, but an account of his life survives in A Genuine Narrative of the Life and Surprising Robberies and Adventures of William Page. Page has often been likened to Fielding’s character Tom Jones, though Fielding penned that eponymous novel before ever encountering Page.

Page was born in 1730 to a working class family. His father died early, so his mother sent him to be an apprentice to a relative, who was a haberdasher. Page hardly had a taste for the work, but he did develop a penchant for fashion and frippery. Alas, a haberdasher’s apprentice hardly earned much income. To fund the fashionable lifestyle he desired, Page undertook his first crime: he robbed his own employer. Likely because of the family connection, Page faced no criminal charges.

Next Page managed to secure a position as a footman to a gentleman, no easy feat given that he had no references. The position gave Page another taste of society life. One day while Page was traveling with his master, the carriage was ambushed by highwaymen. No one was injured, but the robbers made off with a small fortune in a matter of minutes. Page resolved to seek his fortune as a “gentleman of the road.”

After acquiring a horse and pistols, Page immediately committed a series of robberies at Highgate Hill and Hampton Court. Then he held up a Canterbury stage coach on the road from London to Kent. Aware that this early success was thanks to luck, Page decided to take some time and plan future robberies. Posing as a law student, he took lodgings at Lincoln Inn. He traveled extensively around London, creating intricate road maps and scoping out ideal spots for future robberies. Page found a number of suitable locations within about twenty miles of London.

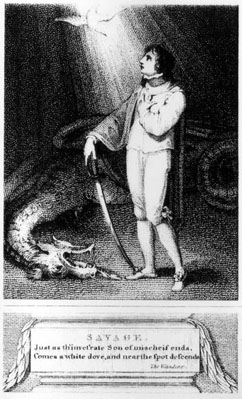

Page also decided that he should assume a disguise to reduce suspicion. He would set off from London dressed as a gentleman driving a phaeton and a pair. Page would find an isolated spot near his intended ambush point, shed his fine attire, and put on old clothes and a wig. After perpetrating his heist, Page would then return to the phaeton and change back into his everyday clothes.

In one instance, Page’s plot went awry. While Page was holding up a carriage, a couple of haymakers stumbled upon his phaeton. Assuming it was abandoned, they took it to the closest village. Page returned to find his carriage—and his fine clothing—had disappeared. He correctly assumed that the thieves would go to the next town and immediately headed there. Page found his phaeton parked outside the local inn. Thinking quickly, Page stripped down to his underwear and threw his clothes down a well. He burst into the inn and announced that he’d been robbed of his carriage and clothes and thrown into a ditch. The innkeeper helped to detain the haymakers till the authorities. Later, Page simply refused to testify against the men.

Over the course of the next three years, Page would commit approximately 300 robberies. All the while, he enjoyed a life of luxury and privilege. Then his accomplice and childhood friend John Darwell made a fatal error. Darwell held up a carriage on his own, and the majority of the men inside were armed. They easily captured Darwell, who then offered to give up Page in exchange for his own release.

Page was apprehended at the Golden Lion in Grosvenor Square. Despite having been captured with a black wig and a detailed map of London in his possession, Page was acquitted due to lack of evidence, but found himself immediately sent to Maidstone Gaol on other charges. Fielding presided over the case and sentenced Page to death. He was hanged on April 6, 1758.

A Genuine Narrative of the Life and Surprising Robberies and Adventures of William Page was originally sold for one shilling. Today it’s a much more valuable record of the era’s attitudes toward crime, punishment, and justice.

Related Posts:

A Brief History of True Crime Literature

Charles Dickens’ Debt to Henry Fielding

Charles Dickens and Capital Punishment

Thanks for reading! Love our blog? Subscribe via email (right sidebar) or sign up for our newsletter--you’ll never miss a post.

The nineteenth century was a time of exploration and discovery in the field of medicine. One man who made significant contributions to the field in America was Elias Samuel Cooper, a surgeon whose aspirations stretched beyond building a successful private practice. Dr. Cooper founded the first medical college in San Francisco, where his techniques drew both controversy and respect from the medical community.

The nineteenth century was a time of exploration and discovery in the field of medicine. One man who made significant contributions to the field in America was Elias Samuel Cooper, a surgeon whose aspirations stretched beyond building a successful private practice. Dr. Cooper founded the first medical college in San Francisco, where his techniques drew both controversy and respect from the medical community.