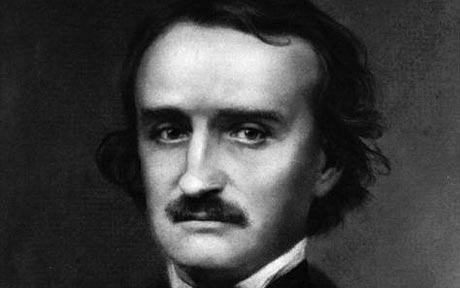

Edgar Allan Poe was the first American writer to earn a living completely by his pen–though that living wasn’t always enough to live on. The legendary author redefined the genre of horror and is rightly called the father of the modern detective novel. But these legacies are the result of a more visceral one: Poe’s ability to evoke an all-encompassing terror that springs not from without, but from within.

Poe’s Incredible Influence

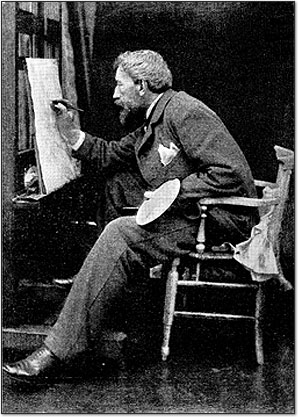

It’s well known that Sir Arthur Conan Doyle used Poe’s C. Auguste Dupin as a model for his own detective, Sherlock Holmes, and that Doyle’s short stories (“Hound of the Baskervilles” in particular) owe a tremendous debt to Poe. Indeed, Doyle once rhetorically asked, “Where was the detective story until Poe breathed life into it?” But Poe’s influence reached beyond the worlds of horror and mystery. He has long been a beloved figure in literature, one whose power has not waned with the passage of many generations.

Poe and Washington Irving exchanged admiration for one another via correspondence. Irving noted that “the graphic effect [of “Fall of the House of Usher”] is powerful.” Poe responded by sending Irving a copy of “William Wilson,” which he considered his best work. Poe admitted that the story had been inspired by Irving himself, particularly Irving’s “An Unwritten Drama of Lord Byron.”

Robert Louis Stevenson said of Poe, “He who could write ‘King Pest’ has ceased to be a human being.” Stevenson found Poe’s stories absolutely gripping, and was undoubtedly flattered when critic Andrew Lang said that Stevenson was “like Poe with the addition of moral sense.”

Meanwhile Oscar Wilde ranked Poe’s poetry as more important than that of Walt Whitman, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Wilde emulated elements of Poe’s style in The Picture of Dorian Gray–which wasn’t lost on Walter Pater, who ardently praised Wilde’s efforts to evoke Poe’s style in the novel. Wilde’s colleague and defender George Bernard Shaw, often an unforgiving critic, was downright effusive about Poe, saying that the American author “constantly and inevitably produced magic where his greatest contemporaries produced only beauty. [His tales are] a world record for the English language: perhaps for all languages.”

Allen Ginsberg argued that “everything leads to Poe….Burroughs, Baudelaire, Genet, Dylan,” and Jorge Luis Borges contended that “contemporary literature would not be what it is” without Whitman and Poe. TS Eliot, however, was not initially convinced of Poe’s genius. He excluded Poe from both American and European literary traditions, calling Poe a “displaced European.” Eliot later acknowledged that he’d underestimated Poe’s talent.

Vladimir Nabokov included multiple allusions to “Annabel Lee” in his masterpiece, Lolita. It appears that Nabokov was indeed deeply interested in Poe; he meticulously mapped the area around Poe’s home and sketched the manifestations of soul in The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (which he taught within the context of Poe). Both documents are currently on view at the Morgan Library’s excellent exhibit, Edgar Allan Poe: Terror of the Soul.

Later on, novelist and screenwriter Terry Southern, author of Dr. Strangelove, was deeply influenced by Poe, especially The Narrative of A Gordon Pym. Southern wrote an appreciation of Poe, called “King Weirdo,” which was published posthumously. And Stephen King has frequently borrowed archetypal themes from Poe’s works for his own horror novels. The Shining reminds us of both “Masque of the Red Death” and “Fall of the House of Usher.”

Collecting Edgar Allan Poe

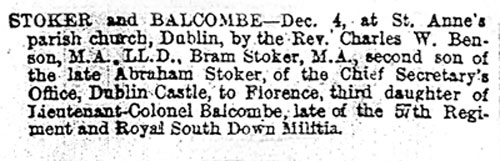

Edgar Allan Poe makes a fascinating focus for a single-author collection and also fits wonderfully into nineteenth-century American literature and horror literature libraries. Poe’s works weren’t actually that popular during his lifetime, so they were issued in relatively small print runs. The first edition of Tamerlane and Other Poems (1827) is famously scarce; only twelve copies are known to exist. (Three are currently on display together at the Morgan Library!)

Even if Tamerlane is out of reach, there are countless other desirable editions and volumes. For example the Poetical Works of Edgar Allan Poe, published by George Robertson in 1868, was the first edition of Poe’s works to appear in Australia. It differs significantly from the British and American editions.

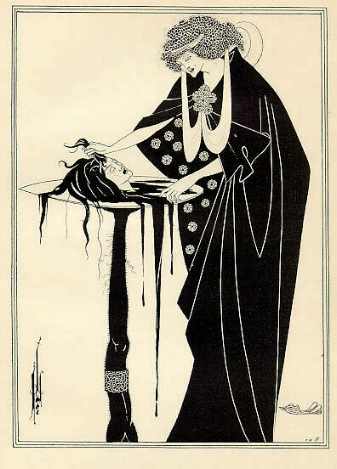

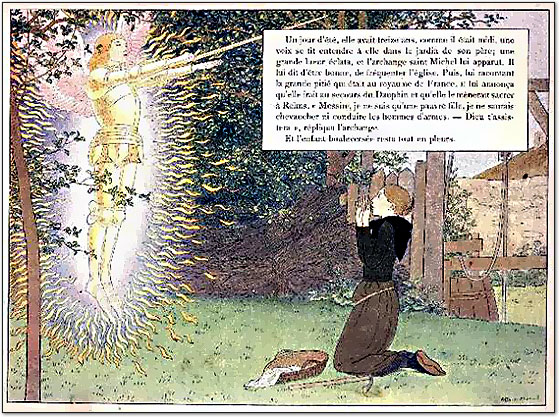

No illustrated editions of Poe’s works were published during his lifetime. The first, Tales of Mystery, Imagination and Humor; and Poems (1852) was illustrated by artists unknown, as they were not given credit for their work. Famous illustrators Edouard Manet, Aubrey Beardsley, Harry Clarke, Edmund Dulac, and Arthur Rackham; first editions of Poe’s works illustrated by these artists are highly desirable.

Poe’s works often showed up in serially issued collections. One of these is The Gift, A Christmas and New Year’s Present for 1842. This compilation includes Poe’s “Eleonora,” along with items from Howard Huntley, Catherine Beecher, and Park Benjamin. The volume also includes an uncollected piece by Lydia Sigourney, “The Village Church.”

When Elizabeth Gaskell first published “Lizzie Leigh,” the story was initially ascribed to Charles Dickens–whose byline meant big bucks for publishers. “Lizzie Leigh” appears under Dickens’ name in The Irving Offering: A Token of Affection for 1851, which also include’s Poe’s “A Descent into the Maelstrom.” The edition is fairly scarce: OCLC records none west of the Mississippi.

Though Edgar Allan Poe enjoys special attention around Halloween, collectors of rare books appreciate his works year round. If you’re looking for a specific item for your Poe collection, please don’t hesitate to contact us! We’re happy to help.