The Rhode Island First Light Infantry Company was formed in 1818 as a state militia company based in Providence. Affiliated with the Second Regiment of the Rhode Island militia, it saw no active duty. Indeed, for the majority of its history the company’s activities were more like those of a social club than of a militia–with a notable exception. The company helped to quell the Dorr Rebellion, even though some of its members actually fought alongside the rebels. Led by Thomas Wilson Dorr, the rebels sought to extend suffrage to the working class. Although Dorr was eventually convicted of treason, his ideas were influential enough that Rhode Island finally revised its archaic voting requirements.

A State Ripe for Revolution

In 1833, Rhode Island’s voting regulations were over 200 years old. Thus the only people who could vote were white, natural born males who owned land. But Rhode Island’s demographics had shifted; the population had grown, but the number of landowners had increased only by a small percentage. Self-educated carpenter Seth Luther was among the first to protest the old voting laws. His “Address on the Right of Free Suffrage” (1833) pointed out that 12,000 working people were at the mercy of Rhode Island’s 5,000 landowners, whom he called “mushroom lordlings, sprigs of nobility…[and] small potato aristocrats.” Luther urged his fellow citizens to stop cooperating with the government, to refuse to pay taxes and serve in the militia.

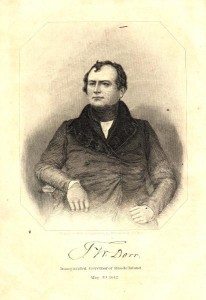

As support for voting reform grew, a somewhat unlikely champion for the cause emerged. Thomas Wilson Dorr was an attorney who hailed from a relatively wealthy family. Dorr served in the Rhode Island General Assembly, and in 1834 he attended a convention at Providence to discuss the issue of universal suffrage (then defined as “voting rights for all males.” But the legislature failed to pass any reforms. By 1841, Rhode Island one of only a few states that hadn’t adopted universal suffrage for white males. it was also the only state that had not adopted its own written constitution. That year the Rhode Island Suffrage Association was founded, and the organization sponsored a demonstration on the streets of Providence.

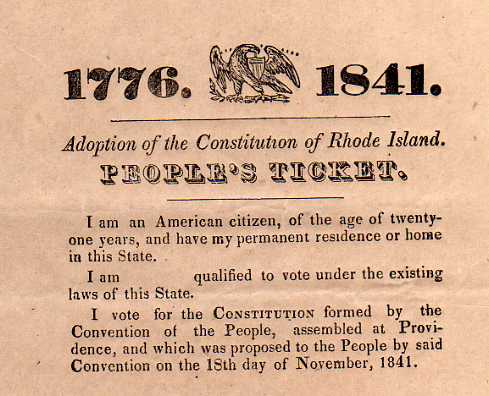

That year, both the Dorrites and the conservatives drew up their own constitutions. The conservative constitution maintained the same voting requirements as the 1663 charter. Meanwhile, at the “People’s Convention,” Dorr and his faction drew up a constitution that permitted all white males to vote. Dorr’s version got approval in referendum, but that was ruled illegal since it hadn’t been called by the government. The government’s constitution was defeated in a separate referendum. It seemed that Rhode Island had reached a stalemate. The Dorrites then decided to put their constitution to a vote. About 14,000 people voted for it, including 5,000 landowners; it won the majority even among only those who were currently allowed to vote. Although the vote was illegal, it did show the government that its citizens supported universal suffrage.

In 1842, both factions went so far as to hold their own elections, and two separate governments emerged. The conservatives were based in Newport, and the Dorrites established themselves in Providence. Dorr ran for governor unopposed and, with 6,000 votes, was elected in April 1842. Obviously this election was also illegal, and Rhode Island’s rightful governor petitioned President Tyler to intercede. He invoked a clause in the US Constitution that permitted the federal government to provide troops to control local rebellions at the request of the state government.

Undone by Racism

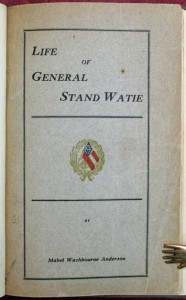

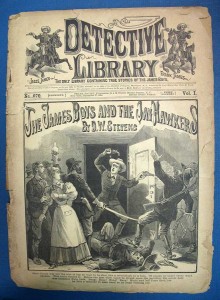

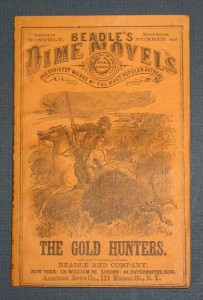

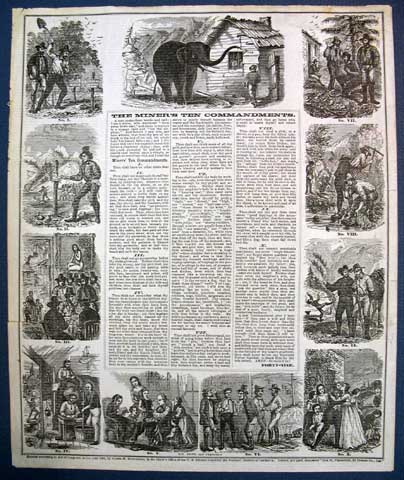

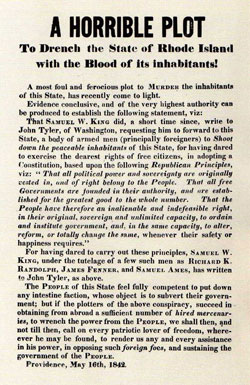

This broadside was published only one day before Dorr staged his rebellion.

Undeterred, the Dorittes held an inauguration ball for Dorr on May 3, 1843. The parade included not only local workers, but even members of the local militia! The parade marched through the streets of Providence. Shortly thereafter, the People’s legislature convened. Dorr’s next move was ill calculated. With the support of many local militia members, Dorr staged an attack on the state arsenal. But it ended quickly and disastrously when a cannon misfired. The government immediately ordered Dorr’s arrest on charges of treason, and Dorr was forced to flee Rhode Island.

And the People’s party had made another terrible move; despite the protests of Dorr and other members, their constitution extended voting rights only to white males. The Rhode Island government used this to its advantage, promising that any new voting legislation would allow blacks to vote. Soon black men were volunteering to join the Law and Order militia, which had been organized to quell the riot and defeat the faction that would deny them the right to vote.

When Dorr came back to Rhode Island, he found that although he had several hundred men ready to fight for his cause, they were far outnumbered by the Law and Order militia. Dorr went back into hiding to regroup. Martial law was declared in Rhode Island. At least 100 rebel soldiers were captured and taken to prison in Providence–after they were put on display, of course.

Rebellion Leads to Reform

Though it appeared that the rebellion had been quashed, legislators now fully appreciated the support for amending suffrage requirements. They drafted a new constitution. The vote was extended to include not only property owners, but also those who paid a one-dollar poll tax. Naturalized citizens could vote if they held at least $134 in real estate. Then elections were held in 1843. The Law and Order group still met opposition from Dorrites, but used intimidation to get people to vote. The conservatives still lost in industrial areas, but got the votes in more rural zones. Ultimately the Law and Order group won the major offices.

That year Dorr returned to Rhode Island and was arrested on the street in Providence. He soon went to trial for treason, and the judge instructed the jury to put aside all political arguments and to ignore Dorr’s motives. They were to reach a decision only on specific, overt acts. Dorr had, of course, admitted to all his actions, so he was speedily convicted. The judge sentenced him to life in prison and hard labor. But Dorr would spend only twenty months in jail; the new Rhode Island governor thought it wise to pardon him, rather than let him languish in prison as a martyr.

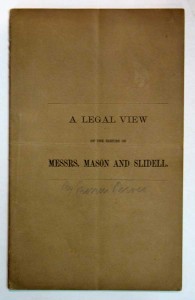

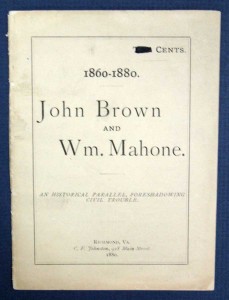

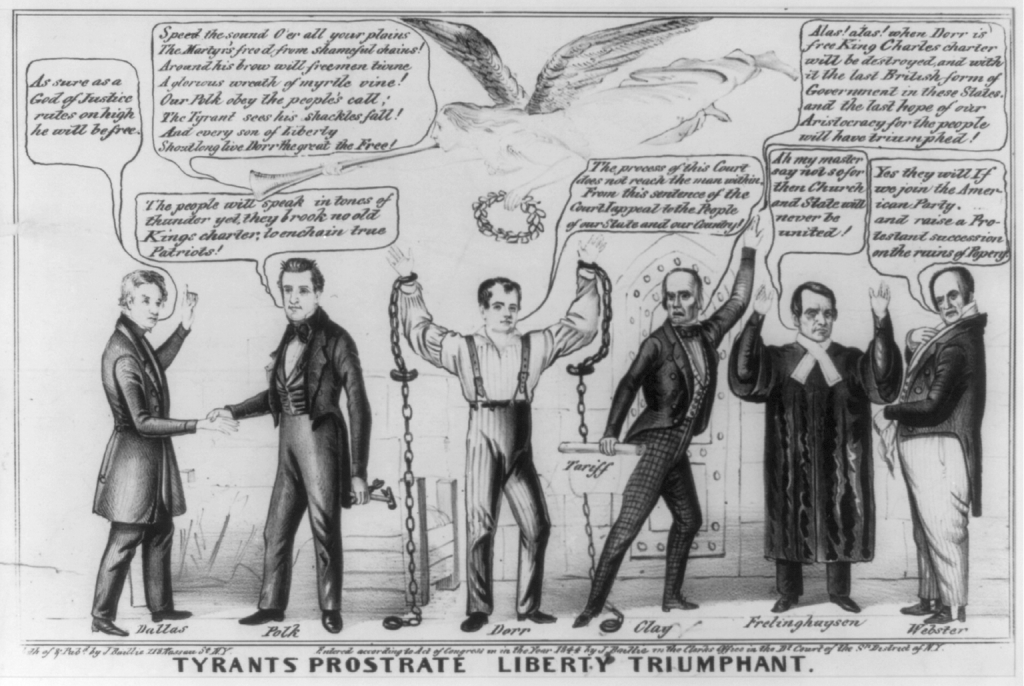

The Dorrite cause still had support even after the rebellion had been quashed, as evidenced in this 1844 polemic.

A Last Stand at the Supreme Court

Though the Dorrites had been defeated, they remained in public consciousness for many more years, most notably through a landmark Supreme Court case. In Luther v Bordn (1849), Luther made a trespassing suit against the Law and Order militia. He alleged that the People’s government was truly a legitimate, elected government in 1842. Daniel Webster defended the militia, arguing that granting such legitimacy jeopardized the very existence of government and could lead to total anarchy. The Supreme Court ruled that it would defer to the President and Congress in matters of war and revolution, a conservative stance.

Though the Dorrites had been defeated, they remained in public consciousness for many more years, most notably through a landmark Supreme Court case. In Luther v Bordn (1849), Luther made a trespassing suit against the Law and Order militia. He alleged that the People’s government was truly a legitimate, elected government in 1842. Daniel Webster defended the militia, arguing that granting such legitimacy jeopardized the very existence of government and could lead to total anarchy. The Supreme Court ruled that it would defer to the President and Congress in matters of war and revolution, a conservative stance.

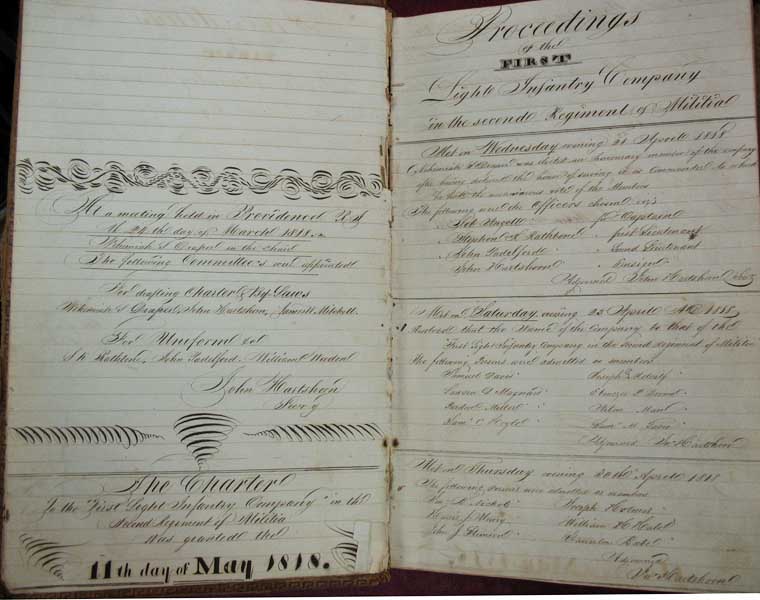

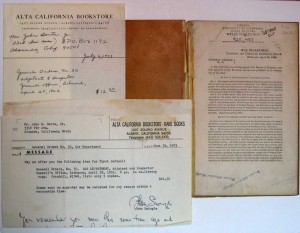

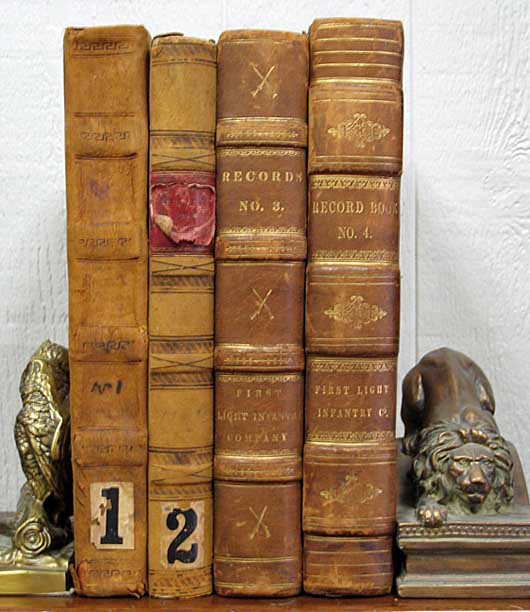

This period was certainly a dramatic one in Rhode Island history, particularly for members of the local militia. The company journals of the Rhode Island Infantry Company, which we’re proud to offer, capture these events as they were experienced by militia members at the time. Handwritten by a series of members, the four-volume set of records stretches from 1818 to 1873, providing exceptional context for quite a long era in American and local history.

Related Posts:

Rare Books in History: The Revolutionary War

Charles Dickens the Copyright Confederate

The Millerites and the Great Disappointment

Thanks for reading! Love our blog? Subscribe via email (right sidebar) or sign up for our newsletter--you’ll never miss a post.