Scholars debate over the etymology of the term “chapbook.” Some argue that “chap” is derived from “cheap,” surely an accurate description of chapbooks, since they were indeed cheap little publications. But the more widely accepted explanation is that “chap” comes from the Old English “céap,” meaning “barter” or “deal.” Peddlers came to be known as chaps, and they were the primary purveyors of chapbooks. Whatever the origin of their name, chapbooks became a vital tool for dissemination of information and promotion of literacy. As publishing and readers’ tastes evolved, chapbooks also provided an ideal means of addressing an increased demand for children’s literature.

Scholars debate over the etymology of the term “chapbook.” Some argue that “chap” is derived from “cheap,” surely an accurate description of chapbooks, since they were indeed cheap little publications. But the more widely accepted explanation is that “chap” comes from the Old English “céap,” meaning “barter” or “deal.” Peddlers came to be known as chaps, and they were the primary purveyors of chapbooks. Whatever the origin of their name, chapbooks became a vital tool for dissemination of information and promotion of literacy. As publishing and readers’ tastes evolved, chapbooks also provided an ideal means of addressing an increased demand for children’s literature.

Since the Middle Ages, traveling peddlers provided many necessary wares to rural communities–and that included the news. They would often regale their customers with the latest in politics, entertainment, and gossip. Then in 1693, England repealed the Act of 1662, which had limited the number of Master Printers allowed in the country. The number of printers exploded. Meanwhile, charity schools emerged, making education and literacy more accessible to the poor. The demand for cheaply printed reading materials drastically increased as a result, and all the new printers were happy to supply their needs.

By 1700, chapmen regularly carried small books–usually about the size of a waistcoat pocket–on virtually every topic imaginable. The books were generally coverless, and their illustrations were made of recycled (and irrelevant) woodcuts from other publications. In the absence of copyright laws, printers would steal illustrations or even large chunks of text from other chapbooks and reproduce them in their own editions. Early chapbooks weren’t even cut; the purchaser would cut apart the pages and either pin or stitch the book together to read.

Chapbooks grew into an incredibly powerful tool for disseminating new ideas. When Thomas Paine published The Rights of Man, he suggested that the second edition be made available in chapbook form. The book went on to sell over two million copies, an incredible feat in those days, when the average publishing run might be only a few hundred or thousand copies. Religious organizations used the form to publish religious tracts, nicknamed “godlinesses” or “Sunday schools.” There were even chapbooks for the chapmen themselves, containing information about different towns, dates for local fairs, and road maps.

Chapbooks grew into an incredibly powerful tool for disseminating new ideas. When Thomas Paine published The Rights of Man, he suggested that the second edition be made available in chapbook form. The book went on to sell over two million copies, an incredible feat in those days, when the average publishing run might be only a few hundred or thousand copies. Religious organizations used the form to publish religious tracts, nicknamed “godlinesses” or “Sunday schools.” There were even chapbooks for the chapmen themselves, containing information about different towns, dates for local fairs, and road maps.

The Industrial Revolution, however, brought a revolution in the printed word as well. People flocked to the cities, reducing chapbooks’ role in news delivery. Newspapers had also become cheaper to produce, so they were no longer relegated to the upper class. And chapbooks’ days seemed numbered when public solicitation was outlawed and peddlers could no longer distribute them. Meanwhile people’s tastes were changing. As the decades of the 1800’s passed, the novel was emerging as a new, preferred form, and in terms of “cheap” literature, chapbooks eventually gave way to “penny dreadfuls,” the dime novel, and other such low-brow forms.

But changing reading habits and higher literacy rates also meant an increased demand for children’s literature. From around 1780, most booksellers offered a variety of children’s chapbooks, which included ABC’s, jokes, riddles, stories, and religious materials like prayers and catechism. Thanks to improved printing techniques, this generation of chapbooks was printed with relevant illustrations and attached colored paper or card wrappers.

Though we think of chapbooks as a distinctly British form, they emerged in various forms around the world. Harry B. Weiss writes in A Book about Chapbooks, “The contents of chapbooks, the world over, fall readily into certain classes and many were the borrowings, with of course, adaptations and changes to suit particular countries.” And despite their variant forms and culturally specific content, chapbooks consistently served as a democratizing force in the dissemination of ideas.

Collectors may build entire collections around chapbooks, or they may find that certain chapbooks fit in well with their collections. For example, the 1849 edition of Juvenile Pastimes includes a rare early pictorial depiction of baseball, making it an ideal addition to a collection of baseball books. Collectors of erotica may enjoy Dumb Dora: Rod Gets Taken Again, an adult chapbook with suggestive, but not pornographic, illustrations. The variety of chapbooks means there’s a little book for everyone!

This month’s select acquisitions are a short list of delightful chapbooks. Please peruse them and contact us if you have any inquiries. As cataloguing chapbooks is quite the endeavor, we’ve also put together an article about the resources used to catalogue the items on the list, which includes our bibliographic sources at the end.

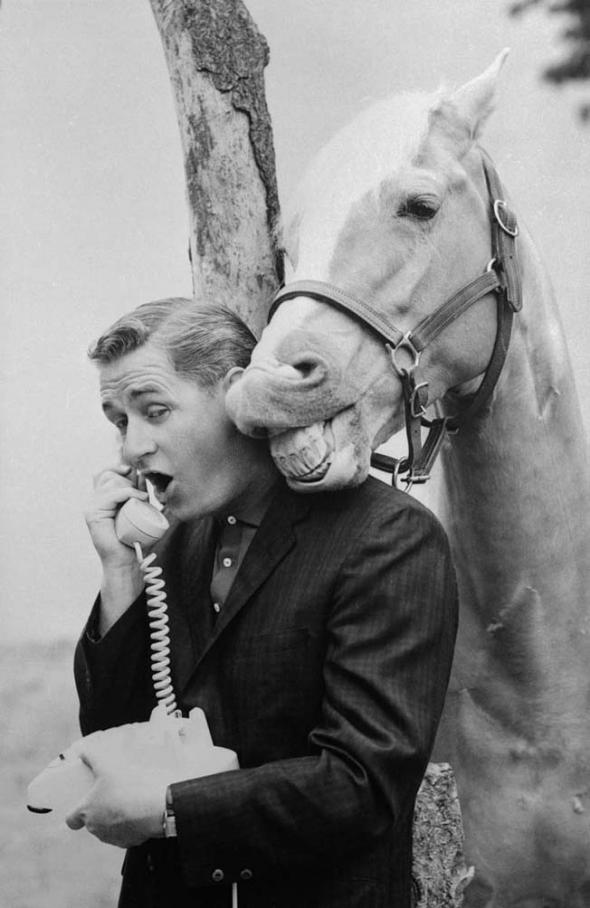

The year 1910 found Brooks in an entirely new field; he worked for Frank Du Noyer advertising agency in Utica. His tenure there proved short, however. In 1911, Brooks “retired.” It’s speculated that when his maiden aunts passed away, Brooks inherited a significant sum. He turned his attention to writing. Brooks was published for the first time in 1915, when his sonnet “Haunted” was printed in Century magazine. That same year, his short story “Harden’s Chance” appeared in Forum magazine. Two years later, Brooks joined the American Red Cross as a publicist. He continued writing short stories, however, and in 1934 began selling stories to Esquire. In total, Brooks published more than 100 short stories, 25 of which featured Ed the talking horse–the inspiration for the TV series “Mr. Ed.”

The year 1910 found Brooks in an entirely new field; he worked for Frank Du Noyer advertising agency in Utica. His tenure there proved short, however. In 1911, Brooks “retired.” It’s speculated that when his maiden aunts passed away, Brooks inherited a significant sum. He turned his attention to writing. Brooks was published for the first time in 1915, when his sonnet “Haunted” was printed in Century magazine. That same year, his short story “Harden’s Chance” appeared in Forum magazine. Two years later, Brooks joined the American Red Cross as a publicist. He continued writing short stories, however, and in 1934 began selling stories to Esquire. In total, Brooks published more than 100 short stories, 25 of which featured Ed the talking horse–the inspiration for the TV series “Mr. Ed.” The Freddy books were by far Brooks’ most popular, and they sold quite well. Set on the Bean Farm in upstate New York, they included both human and animal characters–and the humans never seemed too surprised that the animals could talk. Freddy isn’t a likely hero; he’s quite lazy and manages to accomplish anything only because it’s easier to keep going once he’s gotten started. The novels’ villains frequently represent some form of the Establishment, and the novels’ conflicts generally appeal to children’s sense of fairness and equality.

The Freddy books were by far Brooks’ most popular, and they sold quite well. Set on the Bean Farm in upstate New York, they included both human and animal characters–and the humans never seemed too surprised that the animals could talk. Freddy isn’t a likely hero; he’s quite lazy and manages to accomplish anything only because it’s easier to keep going once he’s gotten started. The novels’ villains frequently represent some form of the Establishment, and the novels’ conflicts generally appeal to children’s sense of fairness and equality.