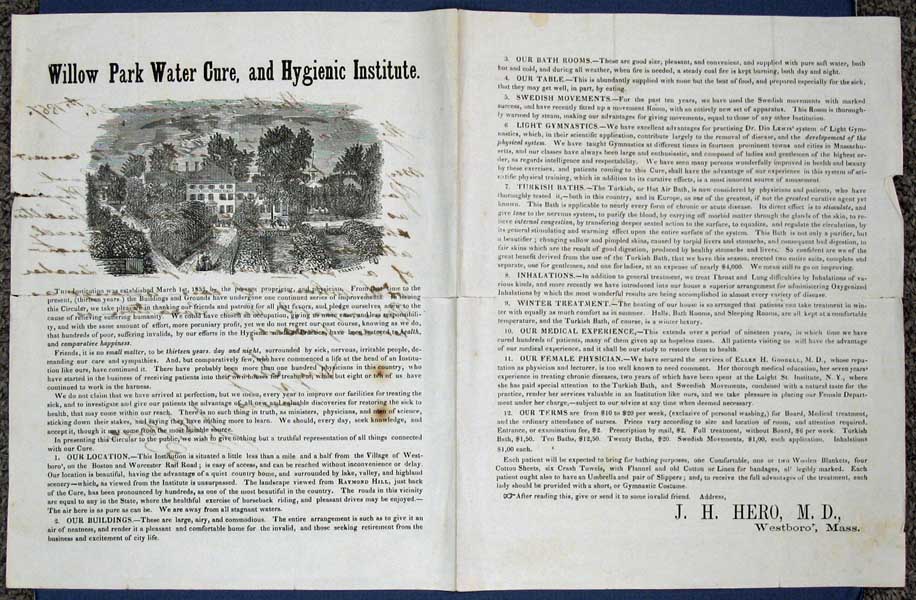

Today we remember Horatio Alger, Jr for his numerous children’s novels–and often little else. The prolific author’s life was shrouded in mystery and fabrication for decades, making him an even more fascinating figure for collectors of rare and antiquarian books.

A Childhood of Privation

Born on January 13, 1832 in Chelsea, Massachusetts, Alger was the son of Reverend Horatio Alger and Oliv (Fenno) Alger. His mother was the daughter of a wealthy local merchant, but the Alger family always struggled financially. Reverend Alger was an able minister, but the post didn’t pay much. After all, as the saying goes, “A doornail is as dead as Chelsea.”

To supplement his pastoral income, the elder Alger served as the town’s postmaster, tended a small farm, and even occasionally taught grammar school. These various pursuits left little time for educating his son; Alger supposedly did not learn his alphabet until he was six years old or receive any formal education until age ten. his education was also skewed toward algebra and Latin.

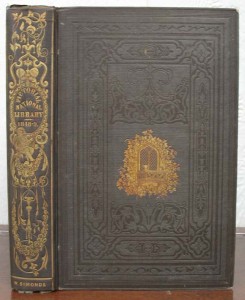

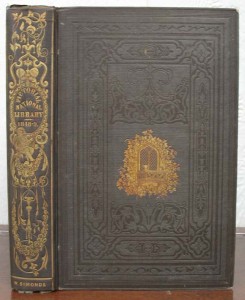

Alger’s work first appeared in print when he was only seventeen years old, in ‘Chivalry & Voices of the Past’ in Pictorial National Library.

Ultimately Reverend Alger’s efforts were insufficient, and he had to surrender the family’s land to creditors in 1844. The family moved to Marlborough, about halfway between Boston and Worchester. Alger attended Gates Academy there for three years, from 1845 to 1847, graduating at age fifteen.

The following year, Alger attended Harvard University. He paid for tuition by acting as the “President’s freshman,” that is, the student who runs errands for the president. Alger’s uncle Cyril Alger, a wealthy industrialist, also contributed to his tuition. Alger distinguished himself as a student, winning numerous academic awards and prizes for his essays. After Alger graduated in 1852, he reflected, “no period in my life has been one of such unmixed happiness as the four years which have been spent within college walls.”

An Uncertain Future

In September 1853, Alger entered Harvard Divinity School–but soon withdrew to take a position as assistant editor of the Boston Daily Advertiser. He soon left that position as well, taking a series of jobs as teacher, principal, and private tutor. During this period, Alger published two hardcover books: a collection of previously published works, Bertha’s Christmas Vision (1856); and the satirical poem Nothing to Do (1857). Even with both teaching and writing, Alger couldn’t earn a decent living. He reentered Harvard Divinity School in July 1857 and graduated on July 17, 1860.

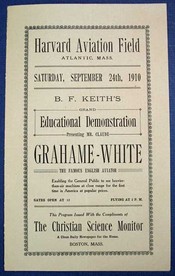

Alger’s first assignment was a congregation in Chicopee, Massachusetts. He took the post and immediately started planning a grand tour of Europe. To fund the trip, Alger agreed to write travel columns for the New York Sun. He set off in September 1860 and would remain in Europe for ten months. Alger returned to an embattled country at the dawn of the Civil War.

Alger’s first assignment was a congregation in Chicopee, Massachusetts. He took the post and immediately started planning a grand tour of Europe. To fund the trip, Alger agreed to write travel columns for the New York Sun. He set off in September 1860 and would remain in Europe for ten months. Alger returned to an embattled country at the dawn of the Civil War.

Though he was drafted, Alger’s poor health and diminutive stature kept him on the home front. Meanwhile, Alger was increasingly frustrated with his inability to make a living as a writer. At this point, the majority of his works had been comedic sketches for adults. Many of them were published under pseudonyms because Alger himself thought them second-rate.

Noting that books for children weren’t exactly in great supply, Alger decided to shift his focus to writing children’s dime novels. He contacted AK Loring with an outline for Frank’s Campaign, a story about a boy who assembles a junior army while his father is fighting in the Civil War. The book was published in 1864. In November of that year, Alger accepted a new ministerial position in Brewster, Massachusetts. While still fulfilling all his pastoral responsibilities, Alger wrote Paul Prescott’s Charge (1865), which received favorable reviews.

In January 1866, two boys in Alger’s congregation accused the minister of having molested them. Alger admitted that his behavior had been “imprudent” and immediately submitted his resignation. Though the congregation wanted to charge Alger publicly, the American Unitarian Association convinced them to keep the matter quiet and be satisfied with Alger’s resignation and the assurance that he would never be a minister again. The congregation acquiesced, and after a brief stint at his parents’ home, Alger moved to New York City.

New Start in the Big Apple

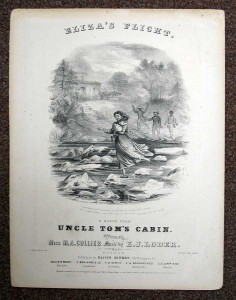

That year Alger published three books: Timothy Crump’s Ward, Charlie Codman’s Cruise, and Helen Ford. The first two were merely revisions of earlier serial strories. The books were well received, but they didn’t generate particularly strong sales. In 1867, Alger submitted Ragged Dick, or Street Life in New York to Student and Schoolmate magazine. Ragged Dick recounted the tale of a young bootblack living on the streets of New York.

The story built on Alger’s fascination with boys who lived on the city’s streets, then known as “street Arabs.” Alger visited the places these boys frequented, including the Newsboys’ Lodging House, where the boys could get a meal and a bed for whatever they could afford to pay. Alger often championed their cause and also took boys in himself. These boys often served as the inspiration for his stories.

Ragged Dick was so popular that Student and Schoolmate invited Alger to be a regular contributor, and Loring published an expanded version later that year. Alger signed on with Loring to write five more books in the Ragged Dick series: Fame and Fortune (1868); Mark the Match Boy (1869); Rough and Ready (1869); Ben the Luggage Boy (1870); and Rufus and Rose (1870). None of these were anywhere near as popular as Ragged Dick. But Alger, determined to make his living as an author, wrote at an incredible pace. He submitted articles to a number of magazines, from Ballou’s and Harper’s, to New York Weekly and Young Israel.

Photo Credit: Stanford University

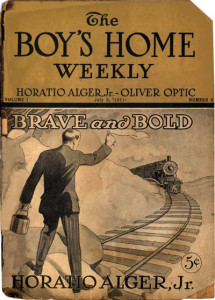

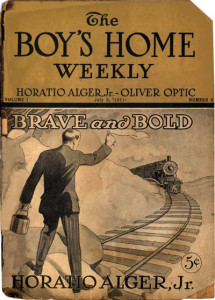

He also agreed to write more series for Loring. These included the “Luck and Pluck Series,” the “Brave and Bold Series,” and the “Tattered Tim Series.” Many of these remained in print for quite a while. It’s evident, too, from the cover of the Boy’s Home Weekly (pictured at right), that Alger’s name sold magazines; that’s why it appears not once, but twice on the magazine’s cover.

Meanwhile Alger still aspired to write for adults–a dream he’d never fully realize. Though a few pieces were published, children’s dime novels financially sustained him. He published a poetry collection, Grand’ther Baldwin’s Thanksgiving in 1875 and a novel called The New Schoolma’am; or, A Summer in North Sparta in 1877.

Alger also wrote a novel called Mabel Parker but decided to wait to publish it because of a slump in the book trade. It would be published posthumously by Edward Stratemeyer with revisions and under the title Jerry, the Backwoods Boy (1904). Gary Scharnhorst published the original version in 1986 under the Archon Books imprint.

Time for Reinvention as an Author

In 1873, Alger took a second tour of Europe, this time returning in time for the stock market crash of 1874. Soon after, he departed on a tour of the western United States. Alger found himself running out of ideas, so he shifted his books’ settings, placing them in new locales rather than big cities. These works sold well, but by this time Alger was publishing to a saturated market. Dime novels for children had proliferated, and Alger’s sales began to drop.

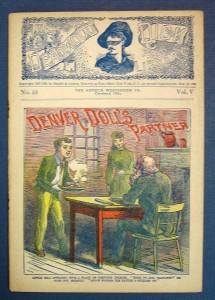

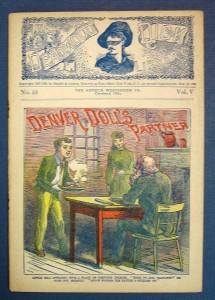

To keep up with the market, Alger began making his stories more lurid. He incorporated violence and criminal activity, similar to what one would find in Edward S Ellis’ Deadwood Dick stories. This proved an ill-advised move. Newspapers, schools, and other organizations had begun protesting violent literature for children.

To keep up with the market, Alger began making his stories more lurid. He incorporated violence and criminal activity, similar to what one would find in Edward S Ellis’ Deadwood Dick stories. This proved an ill-advised move. Newspapers, schools, and other organizations had begun protesting violent literature for children.

The Boston Herald editors specifically called out Alger, noting that “boys who are raw at reading [and want] fighting, killing, and thrilling adventures…go for ‘Oliver Optic’ and Horatio Alger’s books.” Clearly this strategy was not the answer Alger had been looking for.

When President James Garfield died in 1881, Alger’s friend John R Anderson suggested that Alger write a biography of the president for children. By this time, sales were flagging, and Alger needed a new source of income. He reasoned that critics could hardly say something terrible about a presidential biography without seeming unpatriotic, so he gave it a try. Alger put together the manuscript in only fourteen days, using other biographies and news clippings. From Canal Boy to President got good reviews, so Alger wrote two more biographies. From Boy to Senator (about Daniel Webster) was published in 1882, and Abraham Lincoln, the Backwoods Boy came out in 1883.

Alger increasingly spent time out of the city to protect his lungs from smoke and soot. When his health began failing in 1898, he permanently relocated to his sister’s farm. Alger desperately wanted to keep writing, but he simply couldn’t. He decided to hire a ghostwriter to complete the manuscript of Out for Business, settling on editor Edward Stratemeyer. Stratemeyer was ill as well, and was not able to begin work on the manuscript until after Alger had died on July 18th, 1899. By the time Stratemeyer finished the book (both parts – Out for Business and Falling in with Fortune) in 1900, the book would be published posthumously in Alger’s name.

Collecting Books by and about Horatio Alger, Jr

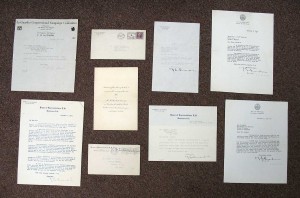

When Alger passed away, his sister respected his wishes that his diaries and personal correspondence be destroyed. That left a momentous task for any would-be biographers. In 1927, Herbert Mayes was commissioned to write Alger’s biography but quickly grew frustrated with the task; there was little extant record of Alger’s life, and his contemporaries were reluctant to share information.

Mayes gave up. He decided to write a parody of Alger instead, opting for the scandalous tell-all format so popular in that era. “All I had to do was come up with a fairy tale…the going was easy, particularly when I decided to write copiously from Alger’s diary. If Alger kept a diary, I knew nothing about it,” Mayes admitted in an introduction to a reissue of his Alger: A Biography Without a Hero.

Mayes did not admit the book was a fake until the 1970’s. By then, plenty of revisions–equally fallacious–had been written. A true biography would not emerge until 1985, with Gary Scharnhorst and Jack Bales’ The Lost Life of Horatio Alger, Jr. For collectors of the author, this plenitude of biographies makes for a fascinating collection in its own right, and the biographies certainly complement a collection of Alger’s literature.

Meanwhile Alger was an incredibly prolific author; by the time of his death, Alger’s name was on 537 novels and short stories (including variant titles); 94 poems; and 27 articles. He also wrote under a number of pseudonyms (the ones we know: Carl Cantab, Harry Hampton, Caroline F Preston, Charles F Preston, Arthur Lee Putnam, and Julian Starr).

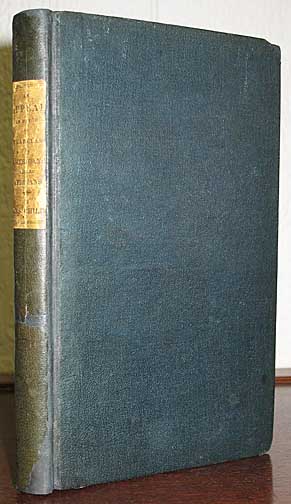

It’s likely that Alger used other pseudonyms we don’t know about, so some of his works may be lost forever. It’s also possible that a savvy collector or scholar could eventually identify other works that should be attributed to Alger. Collectors rely on bibliographies by Bob Bennett and Ralph D Gardner, but sometimes these experts even disagree on bibliographic points. Bennett’s bibliography, A Collector’s Guide to the Published Works of Horatio Alger, Jr 1832-1899 is considered the definitive bibliography.

Because of the sheer number of various Alger editions, a bibliography is indispensable to Alger collectors. It’s important to identify the right points of issue, which may be as obvious as a different title or minute as a tiny artistic detail on the book’s dust jacket. Some books may not be true first editions, but really “first editions thus,” that is, they represent the first time a book was published in a particular format. In some cases, for instance, the paperback edition was published before the hardback, so the hardback book is not the true first edition, but it could still be the first edition thus, meaning it was the first hardback edition. The Horatio Alger Society offers a terrific online guide to identifying first editions, which is a wonderful supplement to a full bibliography.

Ultimately, however, collecting Horatio Alger books will indeed require a bibliography because he so frequently published serially in magazines and other periodicals. These items can be tough to track down because they were not meant to last a long time and were generally printed on very cheap paper. This scarcity is yet another reason why so many find collecting Alger a challenging and engaging pursuit.

Have a question about collecting Alger? Interested in building a personal library of juvenile fiction? We’re happy to help! Please feel free to contact us with inquiries.

Related Posts:

The In’s and Out’s of Collecting Serial Fiction for Children

A Panoply of Primers

Irwin and Erastus Beadle: Innovators in Publishing Popular Literature

Three Pioneering Authors Who Used Pseudonyms

Thanks for reading! Love our blog? Subscribe via email (right sidebar) or sign up for our newsletter--you’ll never miss a post.