In 1854, Sigmund H Goetzel arrived in Mobile, Alabama and immediately got to work setting up a bookstore. A German immigrant who’d been naturalized as a US citizen, Goetzel was intent to establish himself as a prominent member of the city and a vital member of the publishing community. During the Civil War, Goetzel’s publishing house would make waves regarding international copyright law–an issue near and dear to Charles Dickens’ heart. That copyright policy likely contributed to Dickens’ decision to support the South during the Civil War.

An Enterprising Publisher

Goetzel set up shop with silent partner Bernard L Tine, who owned a local clothing store. They called their outfit SH Goetzel & Company. Goetzel would drop the “& Company” once he repaid his debt to Tine in 1863, five years after their partnership had actually expired. Though he remained in the business only eight years, Goetzel proved quite industrious, publishing not only maps and broadsides, but also pamphlets and a number of books. Although many of the books were simply reprints of English or northern titles, a significant number were also original titles.

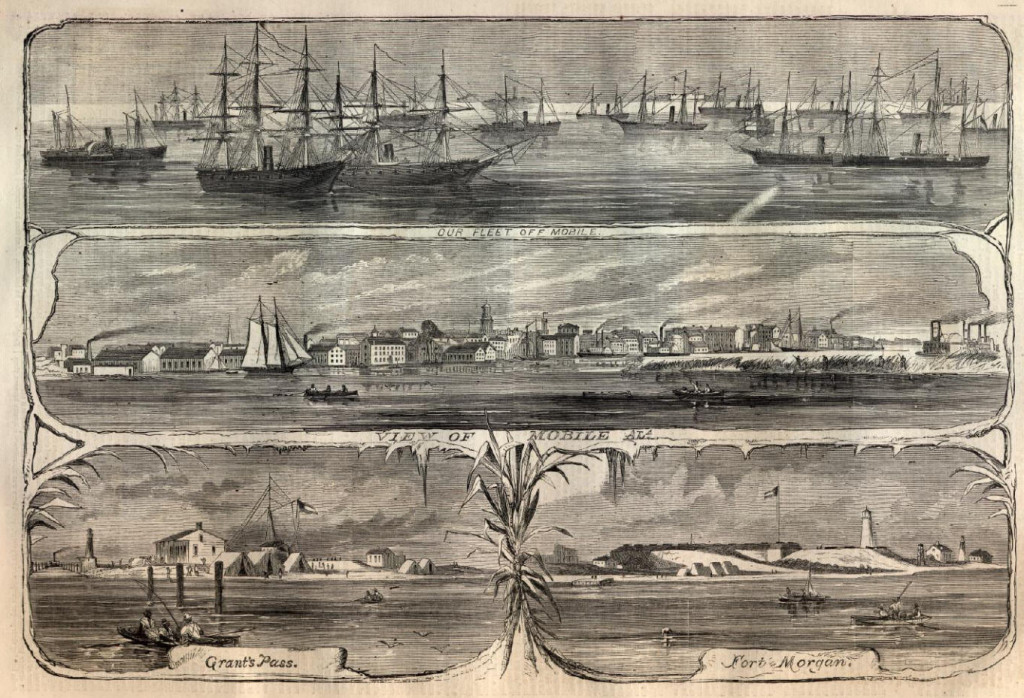

Confederate-era sketches of Mobile, Alabama, from Harpers Weekly

By 1860, the publishing industry in Mobile had grown by leaps and bounds, probably due to increased wealth and an influx of residents. The city was prosperous and cosmopolitan; approximately 50% of its white, male residents were foreign born. Meanwhile in the late 1850’s, Goetzel had consistently garnered praise for the high quality of his publications. SH Goetzel & Company was a thriving part of the Cotton City.

The onset of the Civil War in 1861, however, presented new challenges. Materials, particularly paper and ink, became increasingly difficult to procure from the North, and Union blockades prevented the import of materials from Europe. Goetzel’s main competitor, William Strickland & Company, was driven out of business due to accusations that the firm’s principles were “incendiaries,” that is, abolitionists. By the middle of the war, publishers and printers had either shuttered their shops, or stretched the limits of their ingenuity; thus, wallpaper became a common book covering material when paper and other materials ran out.

Copyright Controversy

Yet Goetzel persevered, anxious to prove to the world that the Southern publishing world would not be undone. His first endeavor was a new edition of William J Hardee’s Hardeen’s Revised and Improved Infantry and Rifle Tactics, which Hardee had revised at the request of Jefferson Davis. Goetzel soon found himself embroiled in a copyright lawsuit, as the work was immediately pirated both in the North and the South. He began printing “THE ONLY COPYRIGHTED EDITION” directly over the title.

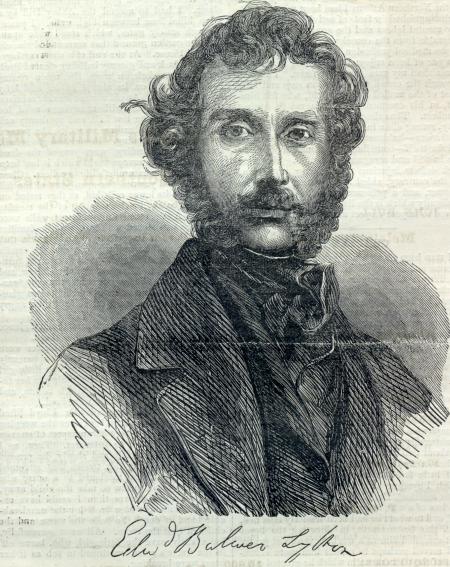

The following year, Goetzel announced that the firm would issue an edition of Sir Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s A Strange Story. Scheduled to start in time for Christmas and New Years, it was issued in numbers. Goetzel published the numbers with such astonishing rapidity, that editors at the Mobile Advertiser and Register noted that the printer’s resources “exceeded expectations.”

The following year, Goetzel announced that the firm would issue an edition of Sir Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s A Strange Story. Scheduled to start in time for Christmas and New Years, it was issued in numbers. Goetzel published the numbers with such astonishing rapidity, that editors at the Mobile Advertiser and Register noted that the printer’s resources “exceeded expectations.”

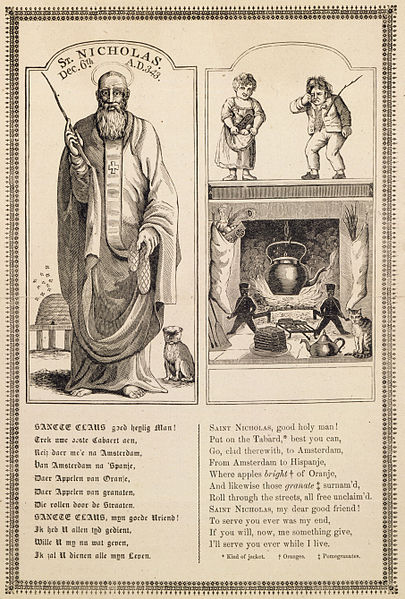

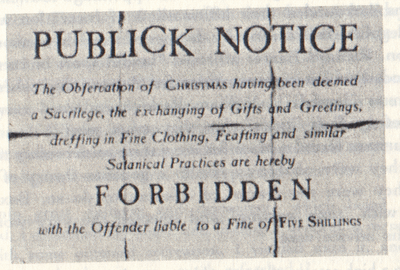

By this time, the Confederate States of America had already established a strong stance on international copyright. On May 21, 1861, the CSA Copyright Act was ratified, granting reciprocal copyright and royalties to foreign-born authors. The legislation was a calculated move, designed to appeal particularly to the British, French, and Germans. And it did garner goodwill tin Europe, particularly in England, where Charles Dickens and other authors had been proponents of copyright law reform for decades.

Thus Goetzel had indeed written to Bulwer-Lytton to obtain permission to print A Strange Story and offer him a payment of $1,000. But thanks to the blockade, the letter never arrived. Bulwer-Lytton announced that the only royalties he’d received had come from his New York City Publisher, Harper & Company. Goetzel wrote a letter of self-defense to the editor of the Mobile Advertiser and Register, arguing that he’d sent Bulwer-Lytton payment and had only recently received confirmation of its arrival.

Thus Goetzel had indeed written to Bulwer-Lytton to obtain permission to print A Strange Story and offer him a payment of $1,000. But thanks to the blockade, the letter never arrived. Bulwer-Lytton announced that the only royalties he’d received had come from his New York City Publisher, Harper & Company. Goetzel wrote a letter of self-defense to the editor of the Mobile Advertiser and Register, arguing that he’d sent Bulwer-Lytton payment and had only recently received confirmation of its arrival.

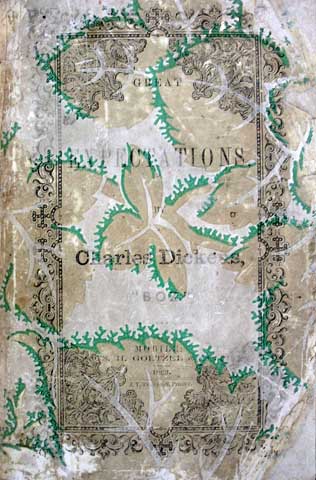

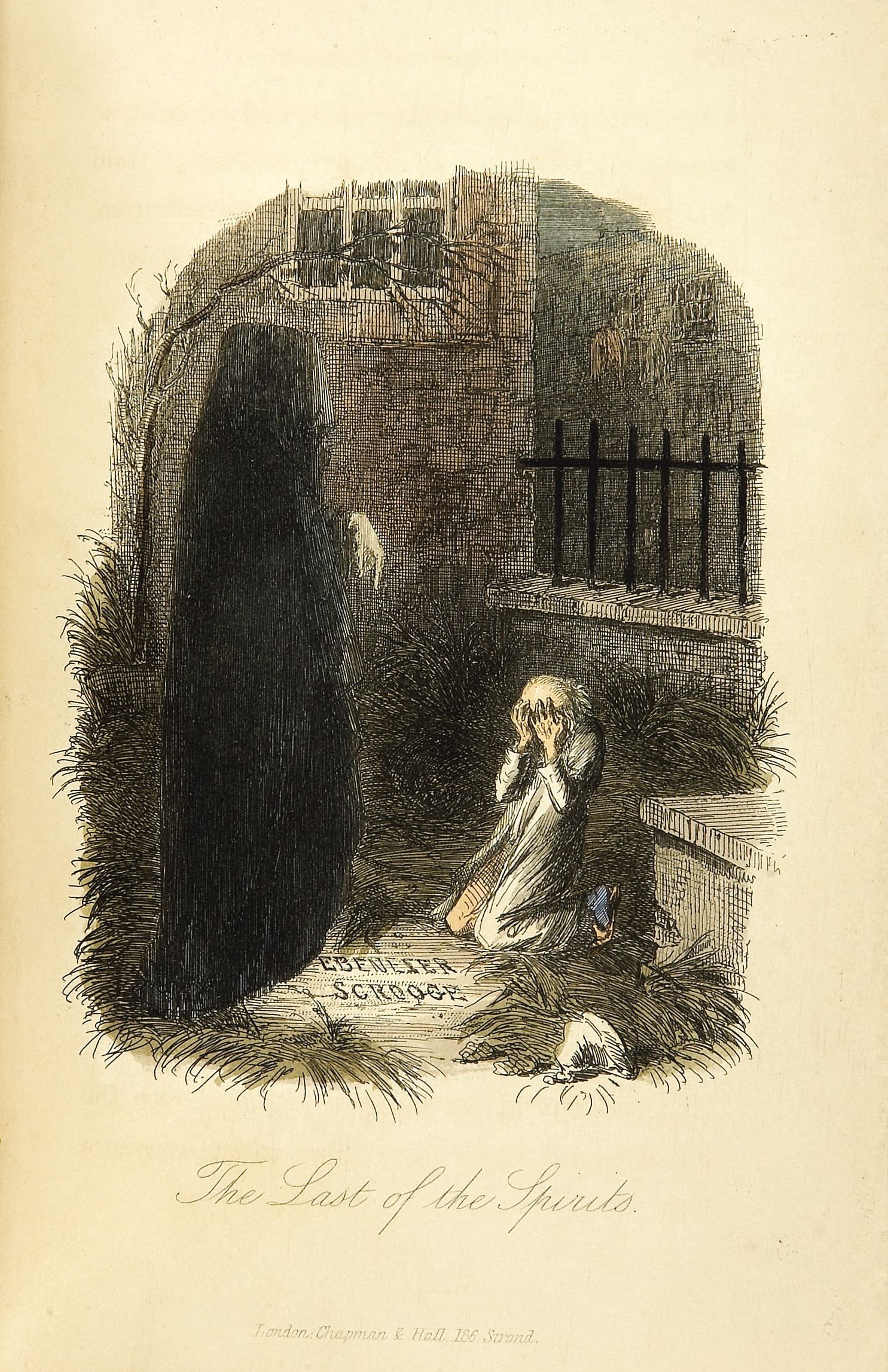

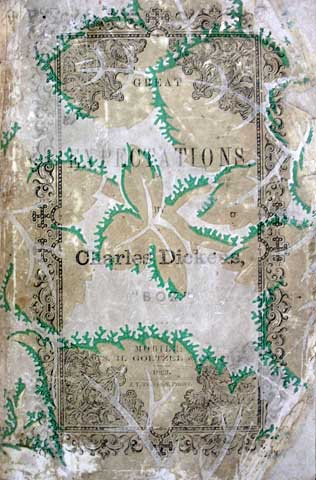

These issues did little to slow Goetzel’s prodigious output. In 1863–the height of the war–Goetzel published five new book-length titles, along with a map, three pamphlets, and a handful of reprints of earlier titles. One of these was an edition of Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations, which was bound in wallpaper. It’s now an incredibly scarce volume. The following year, Goetzel executed six new titles, each about 320 pages.

Dickens’ Sympathies Shift to the Confederates

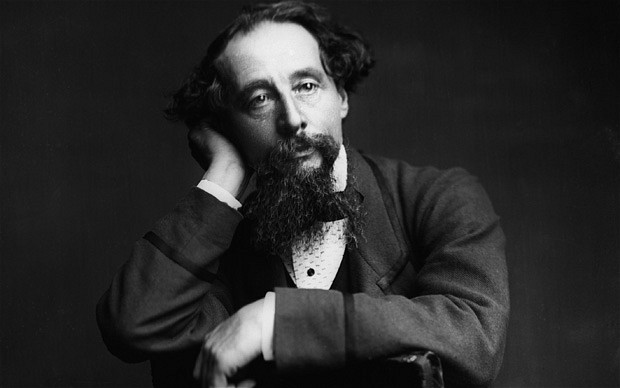

The Civil War had aroused vehement debate in England. Charles Dickens, then the editor of the popular periodical All the Year Round, simply couldn’t remain neutral. Furthermore, Dickens had already taken a decidedly anti-American stance following the debacle of his first visit there. Though American Notes only cast aspersions on the American institution of slavery and the press, Dickens was much more aggressive in Martin Chuzzlewit. The works only served to alienate him further from his American audience.

The Civil War had aroused vehement debate in England. Charles Dickens, then the editor of the popular periodical All the Year Round, simply couldn’t remain neutral. Furthermore, Dickens had already taken a decidedly anti-American stance following the debacle of his first visit there. Though American Notes only cast aspersions on the American institution of slavery and the press, Dickens was much more aggressive in Martin Chuzzlewit. The works only served to alienate him further from his American audience.

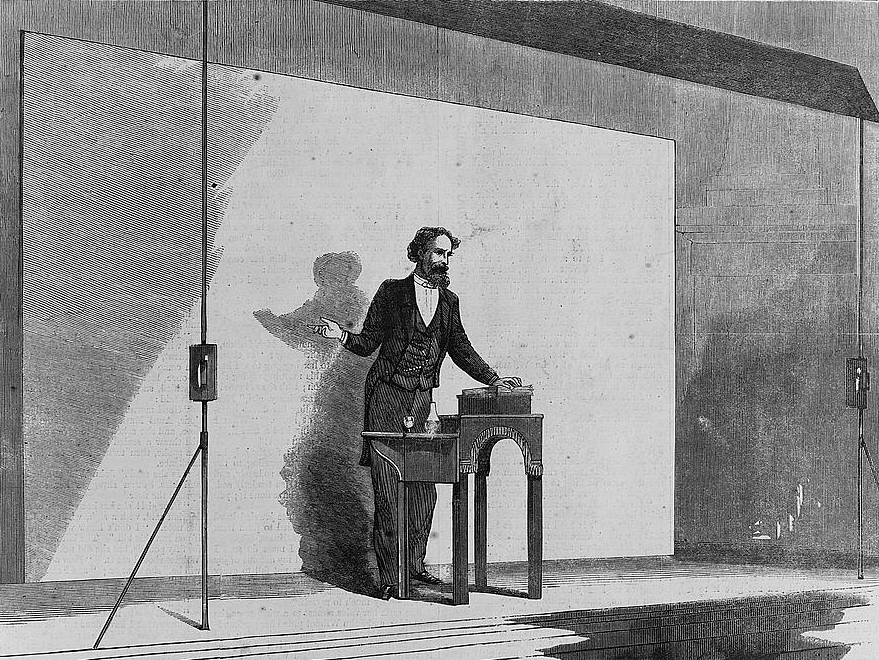

Dickens personally published on the war in All the Year Round only once, on March 1, 1862. He simply republished a number of controversial passages from American Notes with the following note: “The foregoing was written in the year eighteen hundred forty-two. It rests with the reader to decide whether it has received any confirmation, or assumed any color of truth, in or about the year eighteen hundred sixty-two.” The comment implies disdain for both the North and the South. But it also served to vindicate Dickens’ original (and somewhat unpopular) stance in American Notes.

But All the Year Round saw at least 25 pieces about the Civil War. Ever the attentive editor, Dickens carefully supervised every aspect of his publications. That extended to the publication’s political stances which we know thanks to his public announcement following the mid-war printing of Charles Reade’s serialized novel Very Hard Cash, which attacked the Commissioners on Lunacy (which included Dickens’ dear friend John Forster). Dickens said that he took responsibility for the political stances presented in All the Year Round–with the exception only of noted authors’ serial novels that appeared in the periodical.

Appealing to His Readership

Dickens relied on All the Year Round for a substantial portion of his income and had to consider his readers’ interests to ensure sales. Therefore he leaned toward narratives and “true accounts” of the Civil War, rather than news and political commentary. On December 29, 1860, a summary review of Frederick L Olmstead’s A Journey into the Back Country appeared. The book chronicled the most horrifying aspects of slavery in the Lower Mississippi Valley, the least cultured area of the South. The review descried the South’s purported intention to reopen the slave trade.

An article published on July 13, 1861 denounced the South for commissioning privateers to harass British ships delivering goods to the North. Such interference with foreign trade was simply a barbarous tactic. Then on October 26, 1861, a story about an English doctor who treats a runaway slave appeared. It includes all the usual elements: bloodhounds, sketchy Southerners, and a doctor who notes how “wonderfully” the Southerners’ minds have been warped by slavery. A West Virginian character in the story opines, “I only wish we could have a hand on them philanthropists (abolitionists)…A load of brushwood and a lucifer-match will be about their mark, I calculate.”

Spence the English Confederate

By the end of the year, however, the editorial bent of All the Year Round had become decidedly pro-Southern. What happened to change Dickens’ mind? First, he read James Spence’s The American Union, Its Effects on National Character and Policy with an Inquiry into Secession as a Constitutional Right and the Causes of Disruption. Dickens’ copy is inscribed by Spence himself, and the work would deeply impact Dickens’ view of the war.

Historian of the South Frank Lawrence called Spence’s book “the most effective propaganda of all by either native or Confederate agent.” Spence also became active in agitating for the South among England’s working class. He would organize meetings and rallies to counter those held by the Foster-Bright abolitionist groups. So Dickens wasn’t the only British citizen swayed by Spence; he was simply one of multitudes–but perhaps the only one with such a public platform for endorsing Spence’s views.

Dickens was so anxious to review Spence’s book in All the Year Round, he mentioned it more than once in his letters to his assistant editor. After it finally appeared (in not one, but two issues), he was dissatisfied with it. Written by Henry Morley, the review harshly criticizes the Northern cause and contends that the United States is too large to govern honestly and effectively.

A Change of Heart

Dickens was so taken with Spence’s arguments that he espoused them almost unquestioningly. In a letter to his Swiss friend WF de Cerjat on March 16, 1862, Dickens outlines his own views on the war…which are almost entirely borrowed from Spence. He argued that abolition was merely a pretext for other economic aims and “in reality [had] nothing on earth to do” with the Northern war effort. He went on to say, “Any reasonable creature may know, if willing, that the North hates the Negro, and that until it was convenient to make a pretense that sympathy for him was the cause of the war, it hated the abolitionists and derided them up hill and down dale.”

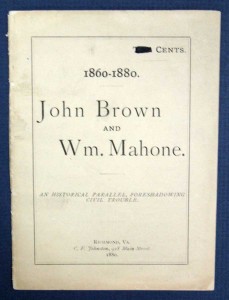

Spence grounds his arguments in the tariff debated that had gripped America even before the South had seceded from the Union. The Morrill tariff, passed on March 2, 1861, replaced the Tariff of 1857, which strongly favored Southerners. The Morill tariff, in contrast, gave preference to industrial workers and placed the South at a considerable disadvantage (hardly a surprise, given that by the time of its ratification, the Southern representatives had left Congress). It also impeded trade with Europe. Two subsequent tariffs during the Civil War helped raise necessary funds for the war.

While Dickens openly adopted Spence’s views, there’s another reason he may have shifted his allegiance: international copyright law. After all, his perspective shifted after the CSA’s Copyright Act had been ratified. And Dickens had long advocated stronger international copyright law; indeed, his first visit to the United States was spoiled because he refused to dismount his copyright law hobby horse and act graciously toward his American hosts and interlocutors. Instead, Dickens pushed his agenda at every opportunity, even using a dinner in his honor as a platform to galvanize fellow authors to his cause.

This issue would have been an emotional one for Dickens, but not one that would garner him much empathy from readers. Better, then, to repeat other, more popular arguments. Thus, it’s quite possible that Dickens privately sympathized with the South because the South seemed to sympathize with his own cause. Whatever his motives, the Confederate imprint of Great Expectations remains a work that will undoubtedly continue to evoke questions and enrapture collectors.

Related Posts:

A Collection of Confederate Literature

How the “Dickens Controversy” Changed American Publishing

Charles Dickens Does Boston

The Two Endings of Charles Dickens’ ‘Great Expectations’

Thanks for reading! Love our blog? Subscribe via email (right sidebar) or sign up for our newsletter--you’ll never miss a post.