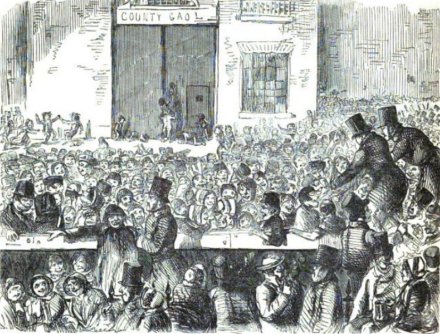

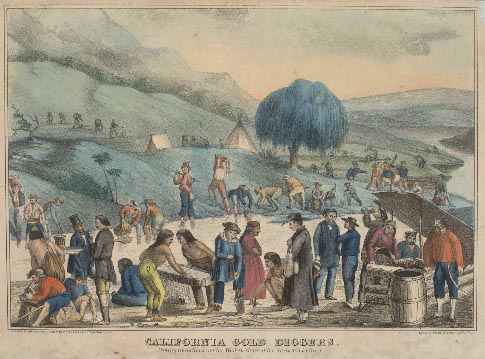

The 1848 California Gold Rush represented one of the largest migrations in the history of the Americas. Over 300,000 people flocked to the state, both from elsewhere in North America and from overseas. The population swelled; San Francisco, for example, went from a sleepy town of 200 in 1846, to a bustling port city of over 30,000 in 1852. Meanwhile California would not officially become a state until September 9, 1850, following much heated debate from Congress.

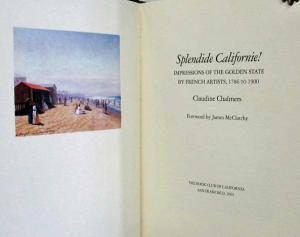

Given the state’s rich history, it’s no wonder that California invites so much fascination from book collectors. The Book Club of California, founded in 1912, published over 100 works, most with some collection to the state. Its first publication was indeed California-centric: Robert Cowan’s A Bibliography of the History of California and the Pacific West (1914, with a second edition in 1933). Robert Greenwood was integral to the publication of two other bibliographies, California Imprints, 1833-1862 and An Annotated Bibliography of California Fictions, 1664-1970, published in 1961 and 1971 respectively. Numerous others come to mind, but we’d be remiss not to mention Gary Kurutz’ The California Gold Rush: A Descriptive Bibliography, 1848-1953. Published in 1997, this is a work of truly enviable scholarship. No other state seems to have garnered so much bibliographic attention.

With this in mind, Tavistock Books presents a list of Californiana, with 100 items related to this state anchoring the “left coast.” While the list has many titles that will cite the bibliographies noted above, this isn’t the list focus. Rather, the list offers printed and visual evidence that California is indeed a state that has long fascinated not only book collectors, but the American populace in general.

Items on the list range from the eighteenth to the 21st century. While many are historical in nature, you’ll also find original art, promotional travel pieces, the first California-published miniature, California fiction, and even on of the first California cookbooks. Prices range from $15 to $3,250.

We invite you to browse the entire list! Should you have queries regarding any of the listings, or other offerings you may find on our site, please contact us.

Selected Californiana

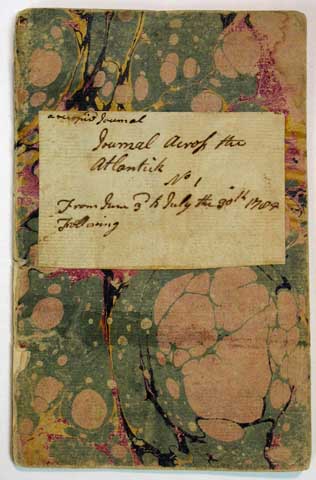

Discovery of California and Northwest America

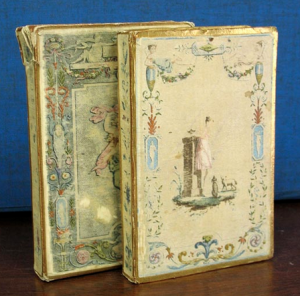

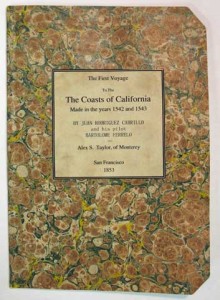

Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo and his pilot, Bartolome Ferrelo reached what is now San Diego in September, 1540. Cabrillo explored the entire outer coast of the peninsula before heading north to the Channel Islands, Monterey Bay, and Point Reyes. Published in San Francisco in 1853, Discovery of California and Northwest America was the first true work of California history to be published in California. This volume has early marbled paper wrappers (recently added) with a printed title label affixed to the front wrapper. It’s chemised and housed in a custom quarter-leather slipcase. Details>>

Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo and his pilot, Bartolome Ferrelo reached what is now San Diego in September, 1540. Cabrillo explored the entire outer coast of the peninsula before heading north to the Channel Islands, Monterey Bay, and Point Reyes. Published in San Francisco in 1853, Discovery of California and Northwest America was the first true work of California history to be published in California. This volume has early marbled paper wrappers (recently added) with a printed title label affixed to the front wrapper. It’s chemised and housed in a custom quarter-leather slipcase. Details>>

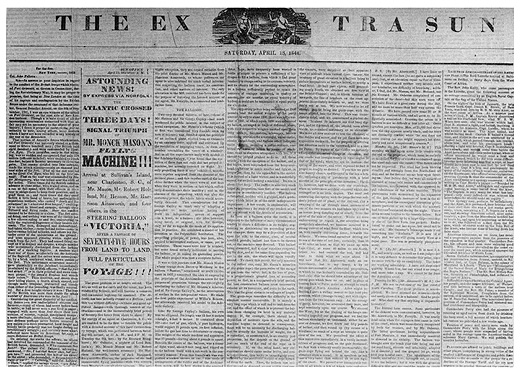

A Trans-Continental Newspaper

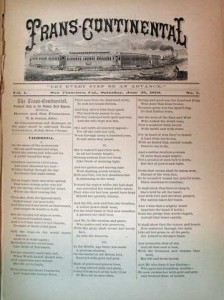

Transcontinental was “Published Daily in the Pullman Hotel Express between Boston and San Francisco.” The twelve issues of Volume I were printed over six weeks, from May 24 to July 4, 1870, while the Boston Board of Trade made the 3,000-mile trek to meet with the San Francisco Chamber of Commerce. They were printed on a Gordon Press in the baggage car, while the newspaper office was in the second car. The paper reported the normal business of the train, along with tidbits such as the Philadelphia Athletics’ victory over the Harvard Baseball Club. The Trans-Continental is generally regarded as the first newspaper printed on a moving train. Details>>

Transcontinental was “Published Daily in the Pullman Hotel Express between Boston and San Francisco.” The twelve issues of Volume I were printed over six weeks, from May 24 to July 4, 1870, while the Boston Board of Trade made the 3,000-mile trek to meet with the San Francisco Chamber of Commerce. They were printed on a Gordon Press in the baggage car, while the newspaper office was in the second car. The paper reported the normal business of the train, along with tidbits such as the Philadelphia Athletics’ victory over the Harvard Baseball Club. The Trans-Continental is generally regarded as the first newspaper printed on a moving train. Details>>

Business Directory of Oakland, Alameda, and Berkeley

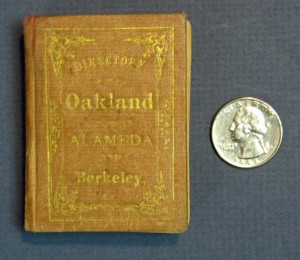

Published in Oakland in 1877, Business Directory of Oakland, Alameda, and Berkeley is not listed in either Norris or Welsh. Extremely rare, this California miniature has the distinction of being the “only known California directory in this format, the first East Bay directory, and the first Berkeley directory of any kind,” according to Quebedeaux, who calls this volume the “first California volume of any kind.” Bradbury refutes this claim, pointing out that Diamond History was also published in 1877 and comprises the latter portion of this volume. OCLC records only three institutional holdings, and there is only one sale record for this item, from PBA earlier this year, of an imperfect copy missing its title page. Details>>

Published in Oakland in 1877, Business Directory of Oakland, Alameda, and Berkeley is not listed in either Norris or Welsh. Extremely rare, this California miniature has the distinction of being the “only known California directory in this format, the first East Bay directory, and the first Berkeley directory of any kind,” according to Quebedeaux, who calls this volume the “first California volume of any kind.” Bradbury refutes this claim, pointing out that Diamond History was also published in 1877 and comprises the latter portion of this volume. OCLC records only three institutional holdings, and there is only one sale record for this item, from PBA earlier this year, of an imperfect copy missing its title page. Details>>

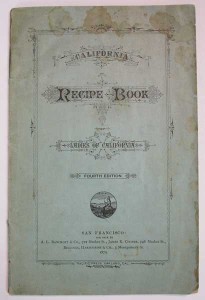

California Recipe Book by Ladies of California

The first edition thus and the fourth edition overall, this copy of California Recipe Book was published in San Francisco in 1879. It was first issued in 1872. The fourth edition bears a note that the “compiler has added largely to the original edition, and our patrons will find many new and choice recipes.” Indeed, the fourth edition includes sixty recipes not found in the first. OCLC records only three institutional holdings, making this a very scarce edition of a seminal California cookery book. California Recipe Book is regarded as the second cookbook written by Californians and published in the state, vying for the title with How to Keep a Husband; Or, Culinary Tactics, also published in San Francisco in 1872. Details>>

The first edition thus and the fourth edition overall, this copy of California Recipe Book was published in San Francisco in 1879. It was first issued in 1872. The fourth edition bears a note that the “compiler has added largely to the original edition, and our patrons will find many new and choice recipes.” Indeed, the fourth edition includes sixty recipes not found in the first. OCLC records only three institutional holdings, making this a very scarce edition of a seminal California cookery book. California Recipe Book is regarded as the second cookbook written by Californians and published in the state, vying for the title with How to Keep a Husband; Or, Culinary Tactics, also published in San Francisco in 1872. Details>>

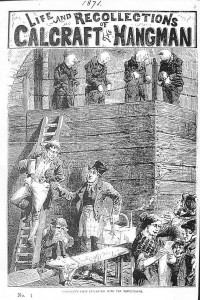

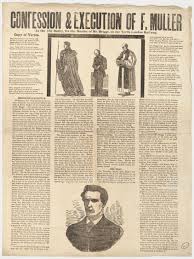

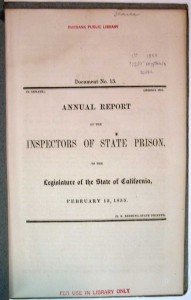

Annual Report of the Inspectors of the State Prison

Made to the legislature of California on February 15, 1855, this report offers an interesting look at the early days of San Quentin, when the prison was not quite impregnable. It includes sections entitled “Register and Descriptive List of Convicts Under Sentence” and “Transcript of Received, Escaped, and Returned Prisoners Since the Inspection of State Prison Books.” The previous year, 75 of the 250 prisoners in San Quentin had escaped without recapture. The statistic alarmed Governor John Bigler, to write in a letter to the prison staff, “These escapes, permit me to remark, give great force to allegations, daily and publicly made, that the prison building is insecure, and that its management is not such as to fully accomplish the object of its erection, in prevention and punishment of crime.” This work is rare, not being listed in Cowan, Greenwood, or the Library of Congress online catalogue. OCLC and Melvyl record only one copy, and no copies have come to auction in at least 25 years. Details>>

Made to the legislature of California on February 15, 1855, this report offers an interesting look at the early days of San Quentin, when the prison was not quite impregnable. It includes sections entitled “Register and Descriptive List of Convicts Under Sentence” and “Transcript of Received, Escaped, and Returned Prisoners Since the Inspection of State Prison Books.” The previous year, 75 of the 250 prisoners in San Quentin had escaped without recapture. The statistic alarmed Governor John Bigler, to write in a letter to the prison staff, “These escapes, permit me to remark, give great force to allegations, daily and publicly made, that the prison building is insecure, and that its management is not such as to fully accomplish the object of its erection, in prevention and punishment of crime.” This work is rare, not being listed in Cowan, Greenwood, or the Library of Congress online catalogue. OCLC and Melvyl record only one copy, and no copies have come to auction in at least 25 years. Details>>

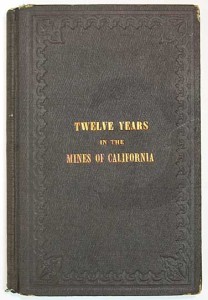

Twelve Years in the Mines of California

Lawson B Patterson arrived in California in 1849 during the Gold Rush and was one of the few who stuck around after the rush ended. Patterson stayed to work the mines for a total of twelve years. Kurutz tells us that in addition to recounting Patterson’s own experiences, “much of this book is devoted to the discovery of gold, the gold region, its geology, advice to new miners, and the weather in 1853. Wheat goes a step further, saying that Patterson’s book contains “observations of permanent import.” This volume’s previous owners include JR Knowland of Oakland Tribune fame, and the ffep bears his PO signature. The book itself is square and tight, with bright gilt. Details>>

Lawson B Patterson arrived in California in 1849 during the Gold Rush and was one of the few who stuck around after the rush ended. Patterson stayed to work the mines for a total of twelve years. Kurutz tells us that in addition to recounting Patterson’s own experiences, “much of this book is devoted to the discovery of gold, the gold region, its geology, advice to new miners, and the weather in 1853. Wheat goes a step further, saying that Patterson’s book contains “observations of permanent import.” This volume’s previous owners include JR Knowland of Oakland Tribune fame, and the ffep bears his PO signature. The book itself is square and tight, with bright gilt. Details>>

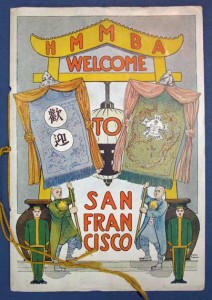

Banquet in Honor of the Hotel Men’s Mutual Benefit Association

This 1910 West Coast journey of HMMBA members was well documented by George Wharton James in his commissioned work, “The 1910 TRIP Of The H.M.M.B.A. To CALIFORNIA And The PACIFIC COAST.” Herein, he remarks this dinner at the Palace was “the most unique and costly dinner ever devised for the HMMBA.” The hotel’s banquet room was presented as a “Mandarin garden decorated with a wealth of Chinese articles of art [loaned by the Sing Chow Co. the menu informs us], and enlivened with … the only Chinese actress in America .. a Chinese theatre and thirty pretty Chinese children with their mothers, a full Chinese orchestra, and a bill of fare as distinctively Chinese as the rest of the function, all aided and abetted by the wealthy Chinese merchants of San Francisco.” As to this souvenir menu, James praises it as “the most elaborate affair ever devised fro the association.” No copy of this item is listed in OCLC; it’s certainly rare. Details>>

This 1910 West Coast journey of HMMBA members was well documented by George Wharton James in his commissioned work, “The 1910 TRIP Of The H.M.M.B.A. To CALIFORNIA And The PACIFIC COAST.” Herein, he remarks this dinner at the Palace was “the most unique and costly dinner ever devised for the HMMBA.” The hotel’s banquet room was presented as a “Mandarin garden decorated with a wealth of Chinese articles of art [loaned by the Sing Chow Co. the menu informs us], and enlivened with … the only Chinese actress in America .. a Chinese theatre and thirty pretty Chinese children with their mothers, a full Chinese orchestra, and a bill of fare as distinctively Chinese as the rest of the function, all aided and abetted by the wealthy Chinese merchants of San Francisco.” As to this souvenir menu, James praises it as “the most elaborate affair ever devised fro the association.” No copy of this item is listed in OCLC; it’s certainly rare. Details>>

Album of Hotel Del Monte

Hotel Del Monte was part of a luxury 20,000-acre resort established by railroad magnate Charles Crocker. The first hotel was completed in 1880, with the entire resort including the hotel, polo grounds, race track, tennis courts, parkland and golf course. Immediately popular, the hotel had to deny 3,000 potential guests its first six weeks of operation. Falling on hard times after WWI, the grounds were eventually sold to Samuel Morse, who eventually led to the development of the present day Pebble Beach facility, among others. The hotel itself now serves as an administration building for the Naval Postgraduate School. This album offers a rare photo-view book depicting the original hotel structure (destroyed by fire in 1887) and diverse associated resort grounds and buildings. Details>>

Hotel Del Monte was part of a luxury 20,000-acre resort established by railroad magnate Charles Crocker. The first hotel was completed in 1880, with the entire resort including the hotel, polo grounds, race track, tennis courts, parkland and golf course. Immediately popular, the hotel had to deny 3,000 potential guests its first six weeks of operation. Falling on hard times after WWI, the grounds were eventually sold to Samuel Morse, who eventually led to the development of the present day Pebble Beach facility, among others. The hotel itself now serves as an administration building for the Naval Postgraduate School. This album offers a rare photo-view book depicting the original hotel structure (destroyed by fire in 1887) and diverse associated resort grounds and buildings. Details>>

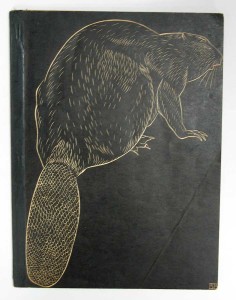

Browny the Golden Beaver

A rare WPA production, Browny the Golden Beaver was published in San Diego in 1938. Belle Baranceanu, who created the cover art, was to achieve some fame as an artist; she painted murals in the La Jolla Post Office and Roosevelt Jr. High School as part of the Public Works of Art Project during the Depression. Baranceanu’s work has been exhibited at the Art Institute of Chicago, Carnegie Institute, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Denver Art Musuem, among other locations. The book was illustrated with drawings by Beatrice Buckley. Details>>

A rare WPA production, Browny the Golden Beaver was published in San Diego in 1938. Belle Baranceanu, who created the cover art, was to achieve some fame as an artist; she painted murals in the La Jolla Post Office and Roosevelt Jr. High School as part of the Public Works of Art Project during the Depression. Baranceanu’s work has been exhibited at the Art Institute of Chicago, Carnegie Institute, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Denver Art Musuem, among other locations. The book was illustrated with drawings by Beatrice Buckley. Details>>

Related Posts:

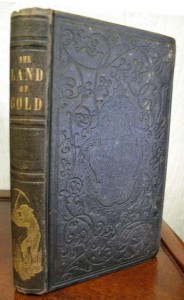

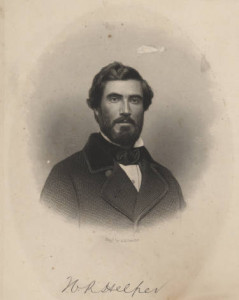

The California Gold Rush, Slavery, and the Civil War

Elias Samuel Cooper: Renowned and Controversial Surgeon

Thanks for reading! Love our blog? Subscribe via email (right sidebar) or sign up for our newsletter--you’ll never miss a post.