On March 25, 1955, US Customs Department officials seized 520 copies of Allen Ginsberg’s Howl. Printed in England, the book had been deemed obscene by the US government. Poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti, who owned the publishing house and book store City Lights in San Francisco, decided to publish Howl in the autumn of 1956. He was almost immediately arrested on charges of obscenity. The ACLU bailed him out and took the lead in his defense. Nine literary experts testified at Ferlinghetti’s trial, and he was found not guilty. Unfortunately, this episode is only one of many in the history of book censorship.

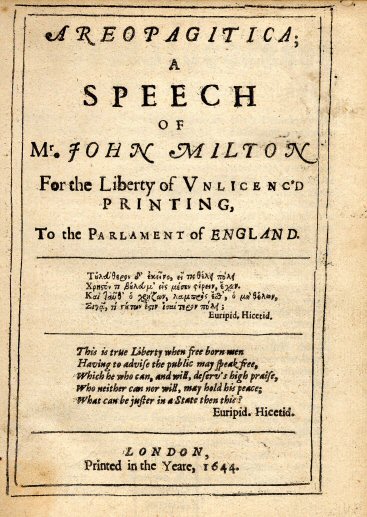

Areopagitica (1644)

By 1644, John Milton had already successfully teamed up with Presbyterians to abolish the Star Chamber. That year, the activist poet turned his attention to the Licensing Act of 1643, which prohibited publication without the permission from the government. In Areopagitica, Milton makes an incredibly eloquent and impassioned plea for an end to government censorship. But he didn’t receive support from Presbyterians, so essentially stood alone in his campaign. The work was banned, and England would not attain freedom of the press until 1695.

By 1644, John Milton had already successfully teamed up with Presbyterians to abolish the Star Chamber. That year, the activist poet turned his attention to the Licensing Act of 1643, which prohibited publication without the permission from the government. In Areopagitica, Milton makes an incredibly eloquent and impassioned plea for an end to government censorship. But he didn’t receive support from Presbyterians, so essentially stood alone in his campaign. The work was banned, and England would not attain freedom of the press until 1695.

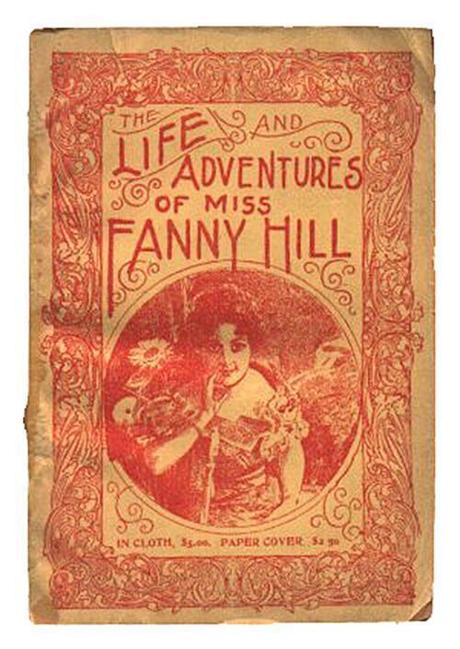

Fanny Hill (1748)

Considered the first pornographic novel published in English, Fanny Hill is every bit as lurid as one would expect from the fictional memoir of a Georgian prostitute. Even more scandalous: the eponymous protagonist enjoys the work of earning “profit by pleasing.” Author John Cleland and the book’s original publisher were immediately thrown into jail after the book was published. And in America, Fanny Hill was the subject of the country’s very first obscenity trial: in 1821, two men were charged with printing an illustrated version. That edition and subsequent contraband editions became hot collector’s items; even Benjamin Franklin was said to have a copy. The book found its way back to the US Supreme Court in 1963 after Massachusetts banned the book. The Supreme Court found the book lewd–and ruled that it was protected by the First Amendment.

Considered the first pornographic novel published in English, Fanny Hill is every bit as lurid as one would expect from the fictional memoir of a Georgian prostitute. Even more scandalous: the eponymous protagonist enjoys the work of earning “profit by pleasing.” Author John Cleland and the book’s original publisher were immediately thrown into jail after the book was published. And in America, Fanny Hill was the subject of the country’s very first obscenity trial: in 1821, two men were charged with printing an illustrated version. That edition and subsequent contraband editions became hot collector’s items; even Benjamin Franklin was said to have a copy. The book found its way back to the US Supreme Court in 1963 after Massachusetts banned the book. The Supreme Court found the book lewd–and ruled that it was protected by the First Amendment.

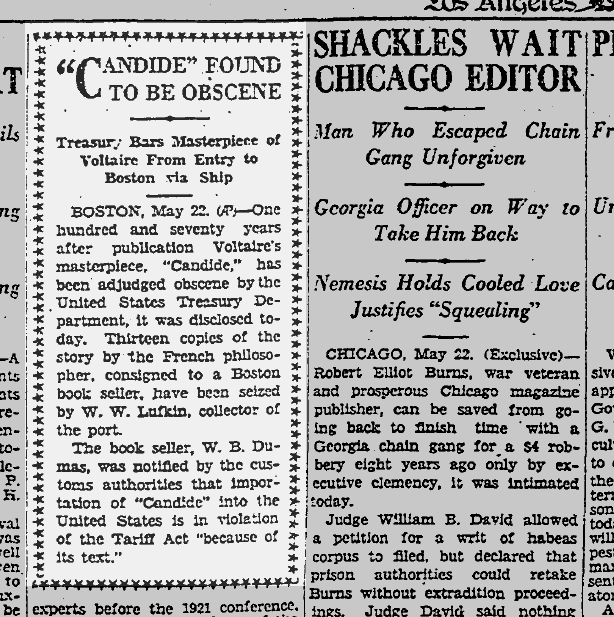

Candide (1759)

Thanks to the book’s catchphrase “Let us eat the Jesuit, let us eat him up” and myriad other irreverences, Voltaire’s Candide was banned by the Great Council of Geneva and the Parisian government just after the book’s release. But 30,000 copies still sold within a year.–much to the delight of Voltaire. The Comstock Law of 1873, later renamed the Federal Anti-Obscenity Act, forbade the sending of obscene materials by US mail. Under this law, the US Customs Department seized Harvard-bound copies of the book in 1930. In 1944, the US Post Office demanded that Candide be dropped from Concord Books’ catalogue. Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, Boccaccio’s Decameron (1350-1353) and a host of other literary works would fall prey to the Comstock Law.

Thanks to the book’s catchphrase “Let us eat the Jesuit, let us eat him up” and myriad other irreverences, Voltaire’s Candide was banned by the Great Council of Geneva and the Parisian government just after the book’s release. But 30,000 copies still sold within a year.–much to the delight of Voltaire. The Comstock Law of 1873, later renamed the Federal Anti-Obscenity Act, forbade the sending of obscene materials by US mail. Under this law, the US Customs Department seized Harvard-bound copies of the book in 1930. In 1944, the US Post Office demanded that Candide be dropped from Concord Books’ catalogue. Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, Boccaccio’s Decameron (1350-1353) and a host of other literary works would fall prey to the Comstock Law.

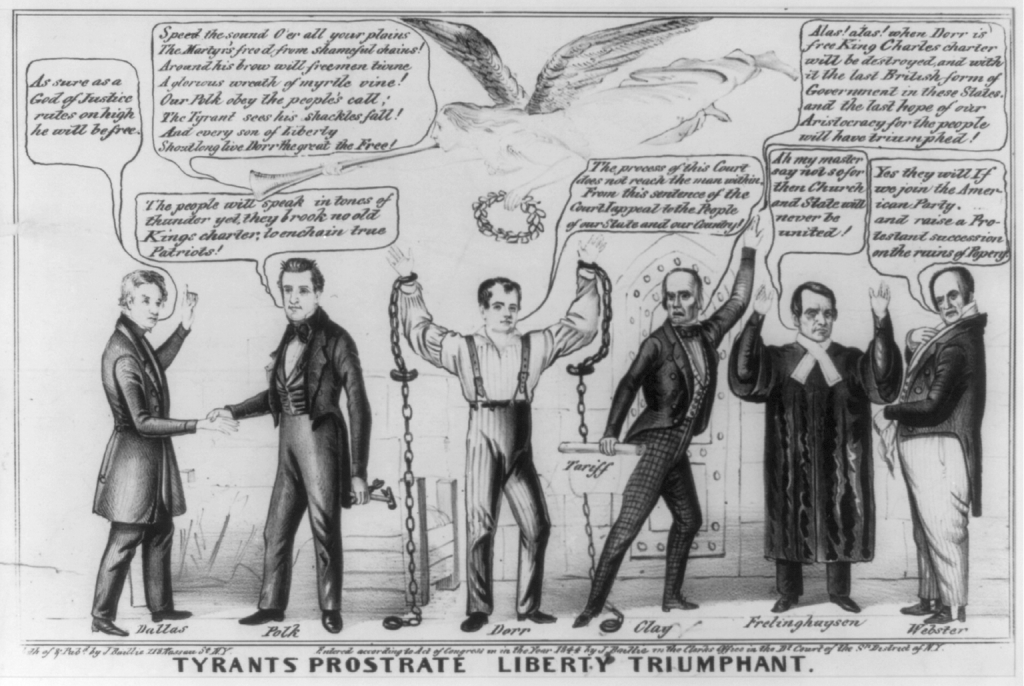

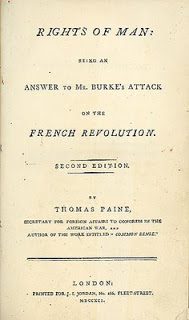

The Rights of Man (1791)

Thomas Paine had already made a name for himself as a dissident with Common Sense (1776) and The American Crisis (1776). In The Rights of Man, Paine vociferously objects to the divine right of kings the inherent right of any family or social class to govern. He also argues that governments should be guided by the will of the people, pointing to France and America as prime examples. The English crown found Paine’s latest work downright treasonous and issued a warrant for his arrest. Paine fled to France, but was found guilty of libel and treason in absentia. He was sentenced to death should he ever enter England again. All copies of The Rights of Man were regularly seized and burned for many years after.

Thomas Paine had already made a name for himself as a dissident with Common Sense (1776) and The American Crisis (1776). In The Rights of Man, Paine vociferously objects to the divine right of kings the inherent right of any family or social class to govern. He also argues that governments should be guided by the will of the people, pointing to France and America as prime examples. The English crown found Paine’s latest work downright treasonous and issued a warrant for his arrest. Paine fled to France, but was found guilty of libel and treason in absentia. He was sentenced to death should he ever enter England again. All copies of The Rights of Man were regularly seized and burned for many years after.

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865)

What could possibly be offensive about Lewis Carroll’s classic Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland? In 1931, General Ho Chein, governer of the Hunan province of China, decided that the book should be banned because its characters included anthropomorphic animals. The general argued that it was “disastrous to put animals and human beings on the same level.” Surprisingly enough, similar arguments have been used in the United States to justify banning Charlotte’s Web (EB White, 1952) and Winnie-the-Pooh (Milne, 1926).

What could possibly be offensive about Lewis Carroll’s classic Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland? In 1931, General Ho Chein, governer of the Hunan province of China, decided that the book should be banned because its characters included anthropomorphic animals. The general argued that it was “disastrous to put animals and human beings on the same level.” Surprisingly enough, similar arguments have been used in the United States to justify banning Charlotte’s Web (EB White, 1952) and Winnie-the-Pooh (Milne, 1926).

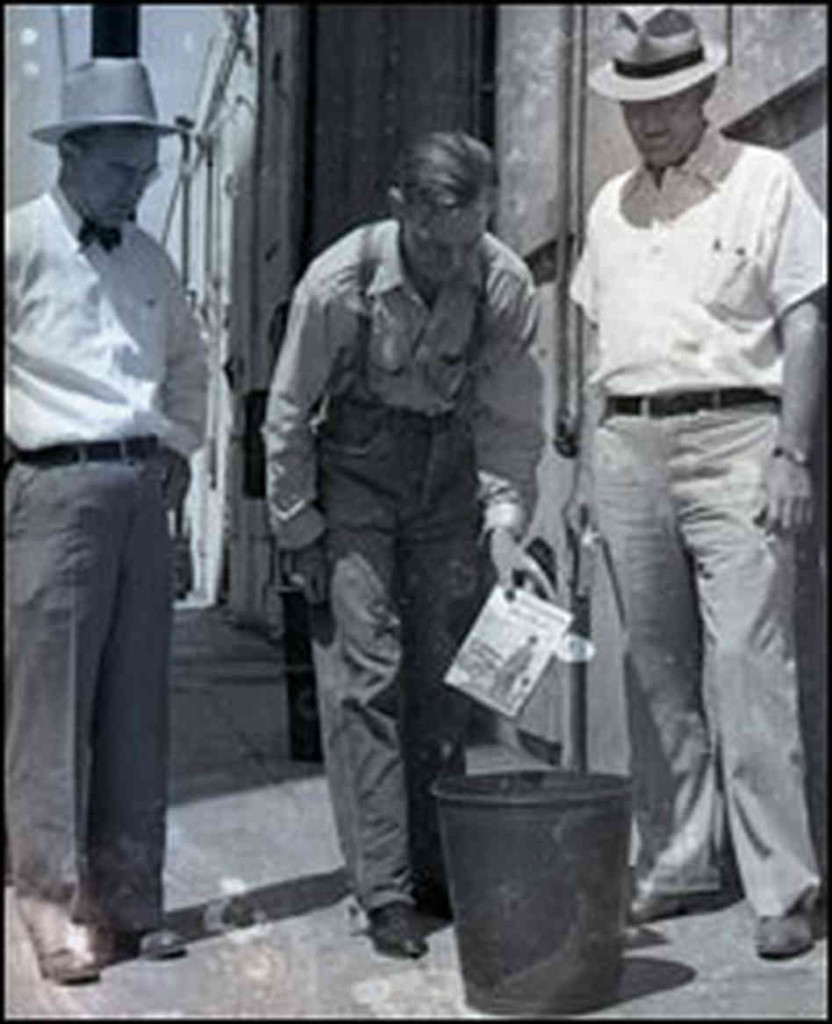

Grapes of Wrath (1939)

Often considered John Steinbeck’s greatest work, The Grapes of Wrath was published to heated outcry. Steinbeck was accused of exaggerating the plight of the poor and unfairly vilifying the wealthy. This reaction was, to some extent, Steinbeck’s intention: he wrote that he wanted to “put a tag of shame on the greedy bastards who are responsible for the Great Depression.” Those who denounced Steinbeck most enthusiastically were the Associated Farmers of California, who called the novel a “pack of lies” and “communist propaganda.” The novel was temporarily banned in parts of the United States–and even burned publicly in some places. The censorship of Grapes of Wrath was pivotal in the creation of the Library Bill of Rights.

Often considered John Steinbeck’s greatest work, The Grapes of Wrath was published to heated outcry. Steinbeck was accused of exaggerating the plight of the poor and unfairly vilifying the wealthy. This reaction was, to some extent, Steinbeck’s intention: he wrote that he wanted to “put a tag of shame on the greedy bastards who are responsible for the Great Depression.” Those who denounced Steinbeck most enthusiastically were the Associated Farmers of California, who called the novel a “pack of lies” and “communist propaganda.” The novel was temporarily banned in parts of the United States–and even burned publicly in some places. The censorship of Grapes of Wrath was pivotal in the creation of the Library Bill of Rights.

Animal Farm (1945)

After George Orwell finished Animal Farm in 1943, it took him two years to find a publisher. The book openly criticized political leadership in the USSR, an important British ally during World War II. After the book was published, it was banned in the USSR and other Communist countries. In 1991, Kenya banned a theatrical adaptation of Animal Farm because it criticizes corrupt leadership. The book was also banned in the United Arab Emirates for containing scenarios and ideas (namely, a talking pig) that conflict with Islamic values. Animal Farm is still banned in Cuba and North Korea, and censored in China.

After George Orwell finished Animal Farm in 1943, it took him two years to find a publisher. The book openly criticized political leadership in the USSR, an important British ally during World War II. After the book was published, it was banned in the USSR and other Communist countries. In 1991, Kenya banned a theatrical adaptation of Animal Farm because it criticizes corrupt leadership. The book was also banned in the United Arab Emirates for containing scenarios and ideas (namely, a talking pig) that conflict with Islamic values. Animal Farm is still banned in Cuba and North Korea, and censored in China.

Green Eggs and Ham (1960)

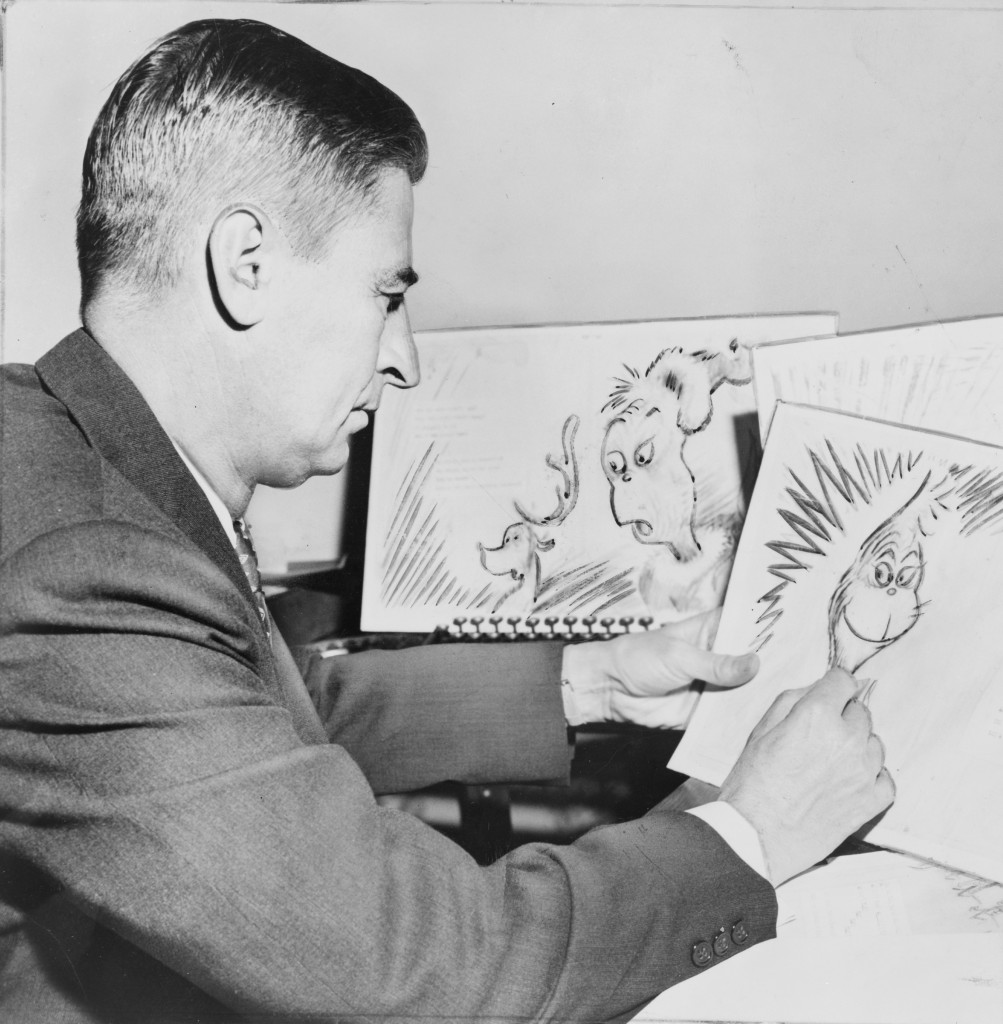

Theodore Seuss Geisel, better known as Dr. Seuss, admitted that he was “subversive as hell” and had no desire to write children’s books that simply modeled good behavior. His books show kids how to question their surroundings and explore new things. Green Eggs and Ham is one of Seuss’ best known works…and it was banned in Maoist China in 1965. According to the Chinese government, the book was a portrayal of Marxism. The ban was not lifted until after Geisel passed away. Meanwhile Yertle the Tertle (1958) was removed from schools in British Columbia in April 2012 because of a single line that carries a political message. And The Lorax (1972) earned a ban from a California community for its negative depiction of loggers.

Theodore Seuss Geisel, better known as Dr. Seuss, admitted that he was “subversive as hell” and had no desire to write children’s books that simply modeled good behavior. His books show kids how to question their surroundings and explore new things. Green Eggs and Ham is one of Seuss’ best known works…and it was banned in Maoist China in 1965. According to the Chinese government, the book was a portrayal of Marxism. The ban was not lifted until after Geisel passed away. Meanwhile Yertle the Tertle (1958) was removed from schools in British Columbia in April 2012 because of a single line that carries a political message. And The Lorax (1972) earned a ban from a California community for its negative depiction of loggers.

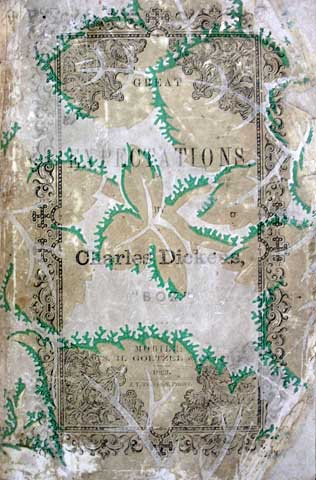

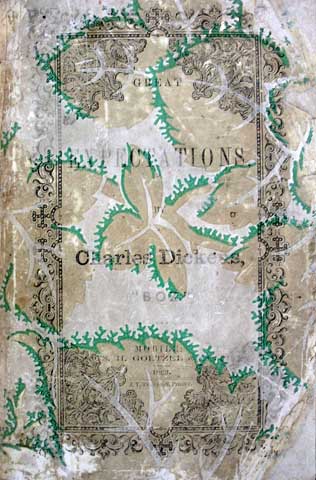

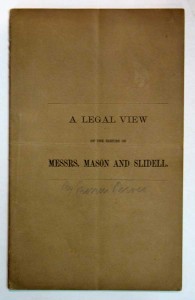

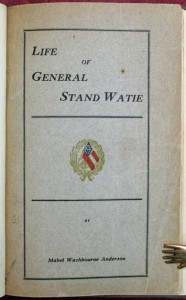

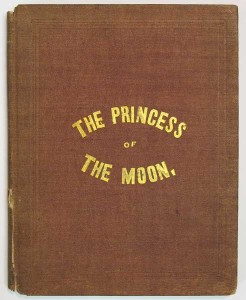

Many of these banned books have become beloved classics for the very reason they were originally banned–they push us to consider uncomfortable ideas that challenge the status quo. Their place in the literary canon has bolstered their desirability among rare book collectors, especially in cases where early editions were frequently confiscated and destroyed.

Related Reading:

AA Milne: Legendary Children’s Author and Ambivalent Pacifist

Fra Paolo Sarpi, Scholar, Priest, and Heretic

Thanks for reading! Love our blog? Subscribe via email (right sidebar) or sign up for our newsletter--you’ll never miss a post.

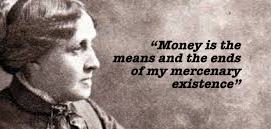

Because Little Women was so obviously based on Alcott’s own childhood, her family gained celebrity along with her. Bronson was quite fond of the attention. Now wealthy and widowed, he sported fine clothes and toured the country as “The Father of the Little Women.” He started publishing (very verbose) volumes of philosophy. Alcott built him the Concord School of Philosophy, so that he could again enjoy lecturing to an audience. His exploits were curtailed by a stroke, and he was forced to retire to a beautiful home in Louisburg Square, provided by his dutiful daughter, who visited almost every day. Alcott, however, wanted nothing to do with fame–perhaps because she saw so little merit in the books that had made her famous. Tourists shamelessly came calling at Orchard House, and Alcott would often pretend to be her own maid to avoid their attentions.

Because Little Women was so obviously based on Alcott’s own childhood, her family gained celebrity along with her. Bronson was quite fond of the attention. Now wealthy and widowed, he sported fine clothes and toured the country as “The Father of the Little Women.” He started publishing (very verbose) volumes of philosophy. Alcott built him the Concord School of Philosophy, so that he could again enjoy lecturing to an audience. His exploits were curtailed by a stroke, and he was forced to retire to a beautiful home in Louisburg Square, provided by his dutiful daughter, who visited almost every day. Alcott, however, wanted nothing to do with fame–perhaps because she saw so little merit in the books that had made her famous. Tourists shamelessly came calling at Orchard House, and Alcott would often pretend to be her own maid to avoid their attentions.