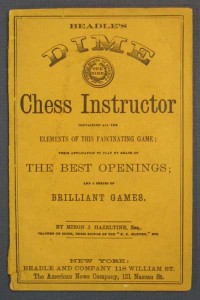

Toward the middle of the nineteenth century, the story papers started giving way to a new publication format: the dime novel. Though a number of American publishers capitalized on the trend, Irwin and Erastus Beadle were likely the most successful. The fruits of their publishing company include numerous series, constituting a unique category of collecting.

Erastus Flavel Beadle was born on September 9, 1821 in Oswego County, New York. Five years later, his brother, Irwin Pedro Beadle, was born. After various apprenticeships, the brothers eventually set up their own stereotype foundry in 1850. The following year, Erastus teamed up with engraver Benjamin Vanduzee to publish the youth magazine The Youth’s Casket. Though Vanduzee would leave the project a few years later, publication continued until 1856. Meanwhile, in 1855, Erastus started his next project: The Home: A Fireside Companion and Guide for the Wife, the Mother, the Sister, and the Daughter.

New City, New Venture

The following year, however, Erastus decided to head west. He hoped to take advantage of the land boom in Kansas and Nebraska. It’s likely that his former apprentice Robert Adams took over publication until his return in 1857. Then in 1858, both Beadle brothers and Adams relocated to New York City. Erastus continued publishing The Home from there, and he brought on Metta Victoria Fuller Victor as the new editor in December, 1858. Victor would become a notable author of several Beadle’s dime novels, including The Dead Letter and Maum Guinea. Her husband would also become an editor for the publishing house for several years.

The following year, however, Erastus decided to head west. He hoped to take advantage of the land boom in Kansas and Nebraska. It’s likely that his former apprentice Robert Adams took over publication until his return in 1857. Then in 1858, both Beadle brothers and Adams relocated to New York City. Erastus continued publishing The Home from there, and he brought on Metta Victoria Fuller Victor as the new editor in December, 1858. Victor would become a notable author of several Beadle’s dime novels, including The Dead Letter and Maum Guinea. Her husband would also become an editor for the publishing house for several years.

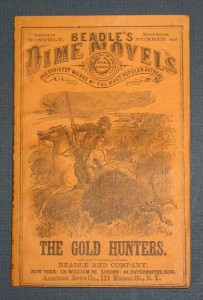

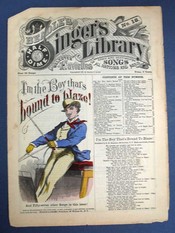

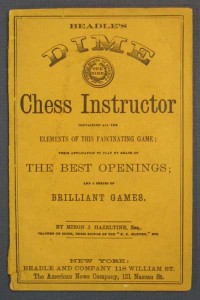

The late 1850’s also saw a new interest in sheet music and popular songs. Irwin capitalized with the Dime Song Book (1859), a paper-bound set of ballads that had previously been published separately. The book sold quite well, so Irwin undertook a series of dime booklets on a wide variety of subjects, from cookery to baseball. At the end of that year, Irwin and Adams formed Irwin P Beadle & Co. Though Irwin would come up with the innovation of publishing dime novels serially, it would be Erastus who got most of the credit–and the profit.

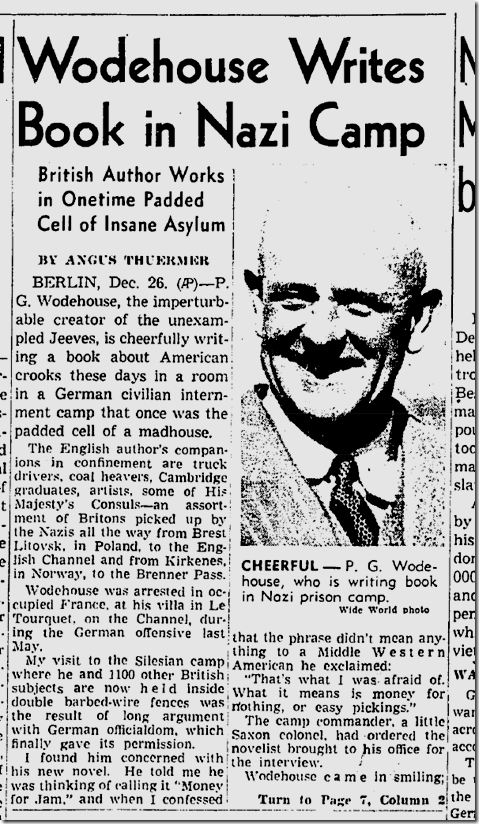

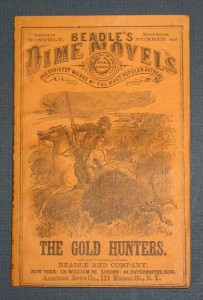

1860 saw the inception of the first Beadle novel series. It kicked off with Ann Stephens’ Maleaska, the Indian Wife of the White Hunter, which had first appeared in Ladies’ Companion magazine (February-April 1839). The story was advertised as “a dollar book for a dime.” In dime novel form, Stephens’ work sold more than 65,000 copies in the first few months. Erastus would later estimate that the eighth novel, Edward Sylvester Ellis’ Seth Jones, sold over twice that, though some experts believe he exaggerated. At any rate, the dime novels, with their orange paper wrappers and patriotic stories, were popular sellers.

1860 saw the inception of the first Beadle novel series. It kicked off with Ann Stephens’ Maleaska, the Indian Wife of the White Hunter, which had first appeared in Ladies’ Companion magazine (February-April 1839). The story was advertised as “a dollar book for a dime.” In dime novel form, Stephens’ work sold more than 65,000 copies in the first few months. Erastus would later estimate that the eighth novel, Edward Sylvester Ellis’ Seth Jones, sold over twice that, though some experts believe he exaggerated. At any rate, the dime novels, with their orange paper wrappers and patriotic stories, were popular sellers.

The Civil War temporarily slowed sales of Beadle’s Dime Novels, but the Union troops were soon reading them as voraciously as ever. Nevertheless, in 1861, Beadle’s American Library was launched in London. It mostly included reprints from the American editions and lasted for five years. In 1862, Erastus and Adams actually bought out Irwin. They didn’t rename the firm Beadle & Adams until 1870, four years after Adams had died and his two brothers, David and William Adams, had assumed his ownership. In the meantime, publications would be issued under several subsidiary names: Frank Starr & Co; Adams, Victor, & Co; and Adams & Co.

Irwin tried his hand at publishing dime novels on his own, but he couldn’t match the efforts of his brother. He gave up the endeavor in 1868. But 31 more novel series would be published, many of these reprints of earlier publications.

Beadle’s New York Dime Library

The longest running of these was Beadle’s New York Dime Library. The series actually began as Frank Starr’s New York Library, and Numbers 1 through 26 were were originally published under this title. Then Number 27 appeared on February 18, 1878 with the title Beadle’s New York Dime Library. When Numbers 1 through 26 ran out, they were reprinted with the new name. Now, it’s almost impossible to find printings with the original name, though occasionally a copy will surface with the new title pasted over the old one. In advertisements, the “New York” was often omitted from the name, likely because it was considered rather insignificant.

The longest running of these was Beadle’s New York Dime Library. The series actually began as Frank Starr’s New York Library, and Numbers 1 through 26 were were originally published under this title. Then Number 27 appeared on February 18, 1878 with the title Beadle’s New York Dime Library. When Numbers 1 through 26 ran out, they were reprinted with the new name. Now, it’s almost impossible to find printings with the original name, though occasionally a copy will surface with the new title pasted over the old one. In advertisements, the “New York” was often omitted from the name, likely because it was considered rather insignificant.

Stories in Beadle’s Dime Library generally hadn’t been published anywhere else first, except for a few serials from story papers. The content was largely the same: stories of adventure, of pioneers and cowboys, of criminals and war heroes. An occasional tale of the sea would be included (notably the pirate stories of the two Ingrahams), but for the most part this genre was considered past its prime. In the late 1870’s and 1880’s, stories of street boys who made their way in the world became increasingly popular. Horatio Alger, Jr was a frequent contributor of these.

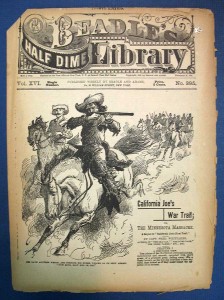

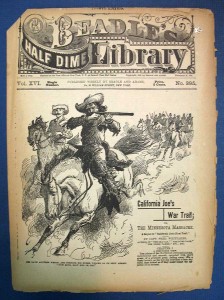

Beadle’s Half-Dime Novels

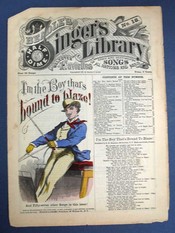

Just five months after Beadle’s Dime Library was launched, Beadle & Adams started the Beadle’s Half-Dime Library. It was geared toward children, who couldn’t always get a dime, but could often scrape together five cents. Experts believe that the first Number most likely appeared on Monday, October 15, 1877, which is actually the same day that the advertisement stating that the series was “coming soon” appeared in Beadle’s Dime Library.

Beadle’s Half-Dime Library was published twice a week until the end of 1877. Starting in 1878, the publication appeared once a week, on Tuesdays, so long as Beadle remained publisher. Some early Numbers have multiple illustrations. For the most part, however, they are illustrated with a single woodcut on the front page. Beadle also squeezed quite a bit of text on each page–often twelve lines of type per inch.

Beadle’s Half-Dime Library was published twice a week until the end of 1877. Starting in 1878, the publication appeared once a week, on Tuesdays, so long as Beadle remained publisher. Some early Numbers have multiple illustrations. For the most part, however, they are illustrated with a single woodcut on the front page. Beadle also squeezed quite a bit of text on each page–often twelve lines of type per inch.

Earlier Half-Dime stories were of adventurers, backwoodsmen, trappers, and hunters. The majority of the stories ran as series. These included Broadway Billy and Joe Phoenix. Deadwood Dick was probably the most successful of these, continuing for over 100 Numbers.

The End of an Era

In 1891, two other similar libraries emerged: Nick Carter Library and Gem Library. Then 1893 saw the establishment of the Bob Brooks Library. And the Tip Top Library and the Diamond Dick Library both started in 1896. But these would be short lived in comparison to Beadle’s Dime Library, which continued a few more years, until 1905. By the end of the 1930’s the dime novel had mostly given way to the pulp magazine.

A Selection of Beadle’s Dime and Half-Dime Publications

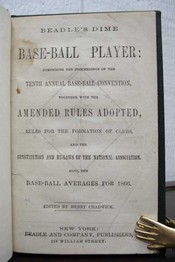

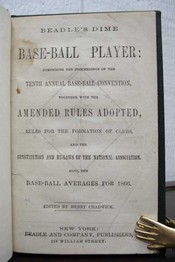

Beadle’s Dime Base-Ball Player (1867)

Beadle’s Dime Base-Ball Player (1867)

Beadle’s Dime Base-Ball Player was published as a continuous series from 1860 to 1881 (none were issued in 1861 or 1863). This is the sixth example. Author Henry Chadwick, is generally regarded as the first sports writer in the US. According to DAB, “the rules of baseball are largely his work.” The series gave rise to the many iterations and laborious study that baseball fans still love today. All of these guides are quite scarce; OCLC shows only one listing of the seventh issue for the nine editions through 1870, and none have come to auction in the last three decades. Details>>

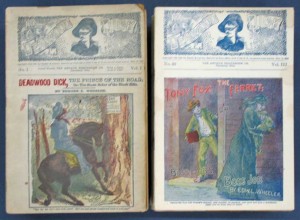

The Deadwood Dick Library

The Deadwood Dick Library

Published in 64 issues, the Deadwood Dick series was penned by Edward Lytton Wheeler. The eponymous protagonist, whose real name is Edward Harris, is considered the quintessential dime-novel hero. Written from 1877 to 1895, the series began publication in Beadle’s Half-Dime Library and was later republished multiple times. This Westwood set is quite rare because it’s complete. Details>>

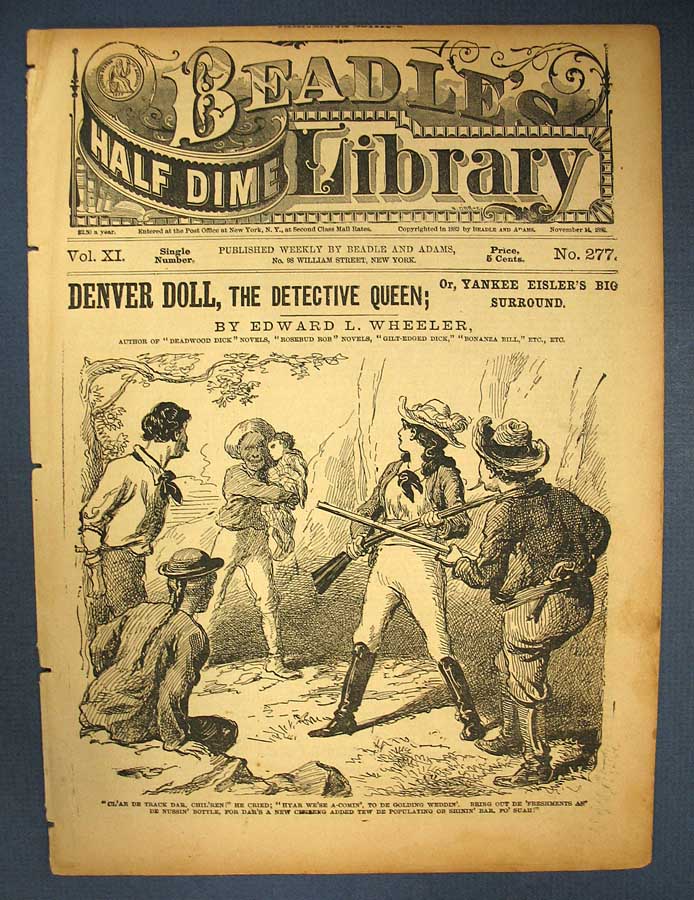

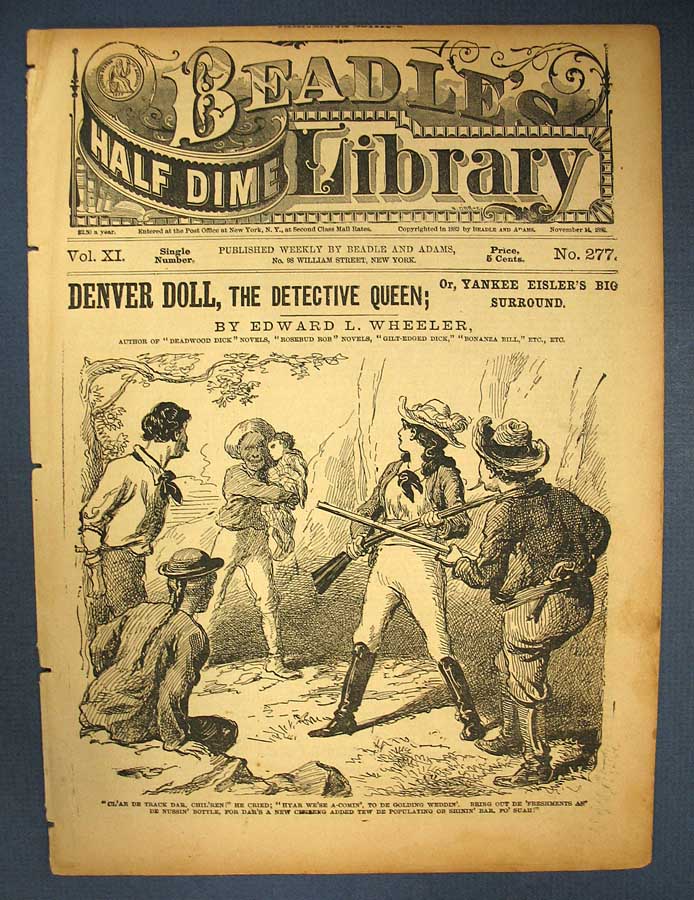

Denver Doll, the Detective Queen

Denver Doll, the Detective Queen

Our research indicates that the “Denver Doll” was one of the earliest female detective characters in American fiction. Wheeler (also responsible for the Deadwood Dick series, above) describes her as “a splendid specimen of young womanhood.” Despite the protagonist’s charm, the series failed to capture the attention of Beadle’s Half-Dime Library readers. The fourth, and last, part of the series was published in March 1883. The series’ short life-span has undoubtedly contributed to its current scarcity. Indeed, even avid mystery collectors are unaware of the Denver Doll and believe that Katherine Green’s Amelia Butterworth (The Affair Next Door, 1897) is the first female detective in US literature. This is the first of the Denver Doll series and can be said to be quite rare. Details>>

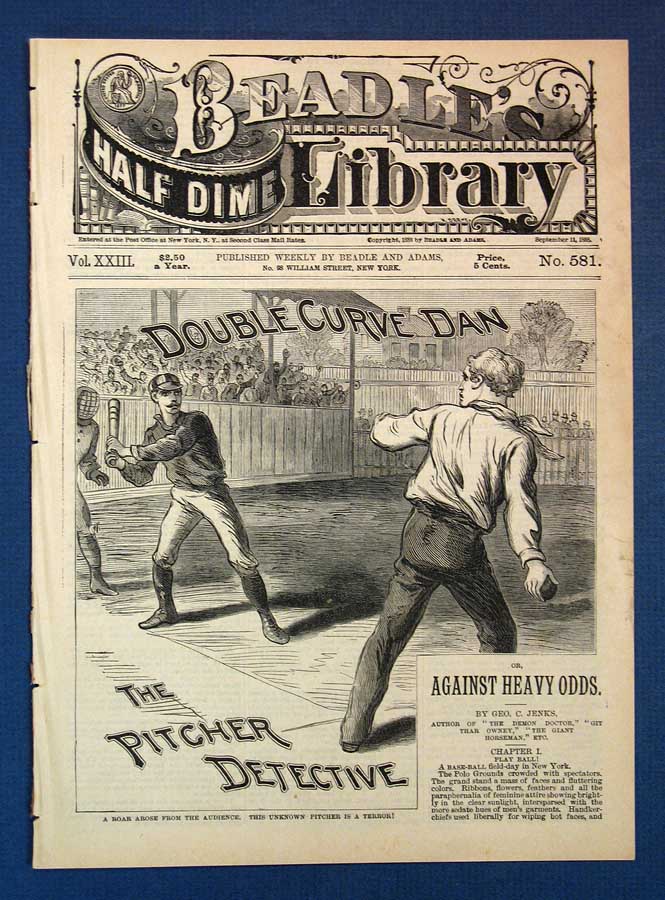

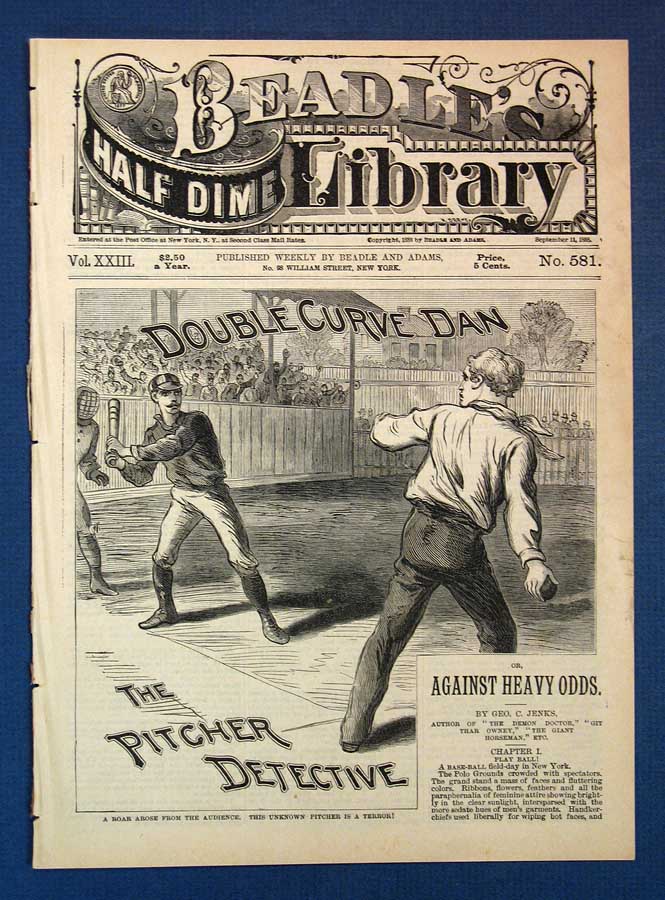

Double Curve Dan, the Pitcher Detective

Double Curve Dan, the Pitcher Detective

George Jenks penned three stories for the Double Curve Dan series. This is the first in the series. OCLC shows only three institutional holdings, and no copies have been at auction in the past thirty years. This copy shows evidence of previous binding, but is otherwise a very good copy of a quite fragile item. Details>>

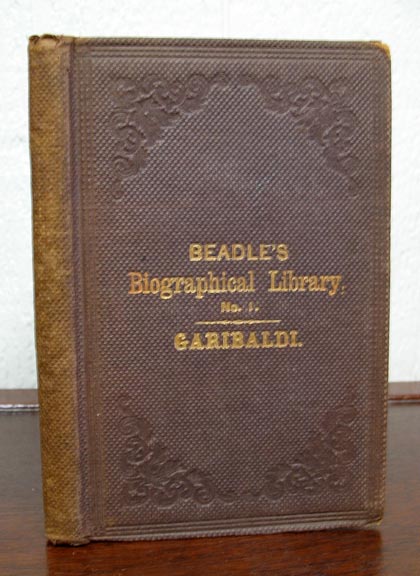

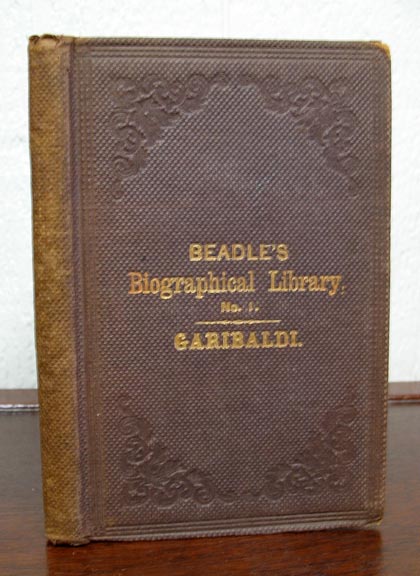

The Life of Joseph Garibaldi, the Liberator of Italy

The Life of Joseph Garibaldi, the Liberator of Italy

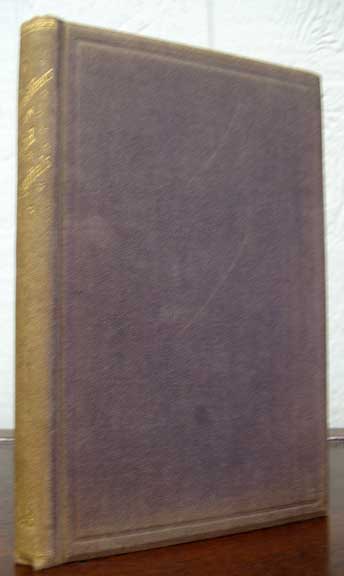

In addition to the popular dime novel series, Beadle & Co launched another series in 1860. Beadle’s Dime Biographical Library presented biographies of famous figures from all over the world. This first edition of The Life of Joseph Garibaldi (1860) has proven a quite rare Beadle publication, especially in this cloth binding (which is not mentioned in Johannsen). It includes an engraving of Garibaldi on the frontis. Details>>

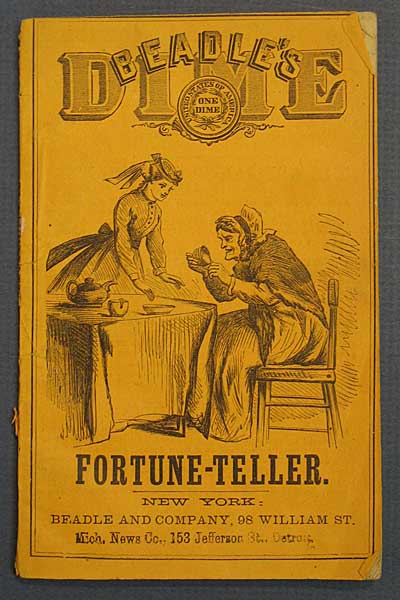

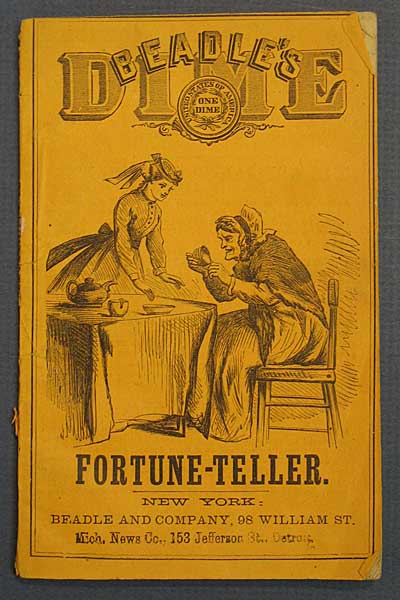

Beadle’s Dime Fortune-Teller

Beadle’s Dime Fortune-Teller

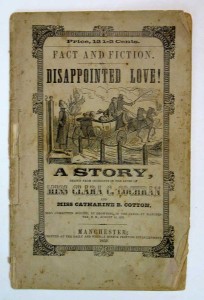

The woodcut on the front of this pamphlet depicts an old crone telling the fortune of a young maid. The book promises to demystify dreams and instruct the reader to discern his fortune in everything from tea leaves to egg whites. First published in October 1868, this is an early reprint, circa December 1868. OCLC records just one institutional holding, at NIU. Details>>

Born on February 12, 1777, Fouqué was a descendent of French Huguenots. His grandfather was a general for Frederick the Great, and his father was a Prussian officer. Fouqué himself didn’t intend to have a military career. Instead, he went to Halles. But in 1794, he left school to join the army and participate in the Rhine campaign. Fouqué would again see battle in 1813, during the uprising against Napoleon. By this time, nationalism had taken deep root in Germany, and these sentiments came to influence Fouqué’s writing.

Born on February 12, 1777, Fouqué was a descendent of French Huguenots. His grandfather was a general for Frederick the Great, and his father was a Prussian officer. Fouqué himself didn’t intend to have a military career. Instead, he went to Halles. But in 1794, he left school to join the army and participate in the Rhine campaign. Fouqué would again see battle in 1813, during the uprising against Napoleon. By this time, nationalism had taken deep root in Germany, and these sentiments came to influence Fouqué’s writing. Tolkien scholar Amy H Sturgis notes that The Magic Ring (1813) is a sort of “missing link in the story of Tolkien’s One Ring.” The legend began several centuries ago with the Siegfried story of Norse legend. It also appears in the Nordic Sagas and Eddas, along with the Middle High German Nibelundenlied. Over time the legend evolved, but Fouqué’s adaptation proved incredibly influential. It was taken up by Richard Wagner in his Ring Cycle and by JRR Tolkien in the Lord of the Ring series.

Tolkien scholar Amy H Sturgis notes that The Magic Ring (1813) is a sort of “missing link in the story of Tolkien’s One Ring.” The legend began several centuries ago with the Siegfried story of Norse legend. It also appears in the Nordic Sagas and Eddas, along with the Middle High German Nibelundenlied. Over time the legend evolved, but Fouqué’s adaptation proved incredibly influential. It was taken up by Richard Wagner in his Ring Cycle and by JRR Tolkien in the Lord of the Ring series.

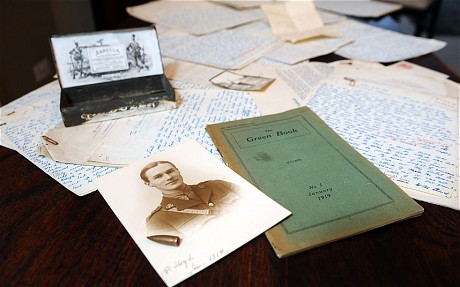

Revered scientist Robert Hooke was one of the original fellows of the Royal Society and the curator of the group’s experiments. He was also responsible for recording the organization’s minutes from 1661 to 1682. The minutes make for fascinating reading, not least because of Hooke’s own asides and commentary. They recount many seminal moments in science, including the earliest work with a microscope and the first sightings of sperm and micro-organisms. This fascinating 500-page document didn’t show up until 2006, when it was discovered in a dusty cabinet.

Revered scientist Robert Hooke was one of the original fellows of the Royal Society and the curator of the group’s experiments. He was also responsible for recording the organization’s minutes from 1661 to 1682. The minutes make for fascinating reading, not least because of Hooke’s own asides and commentary. They recount many seminal moments in science, including the earliest work with a microscope and the first sightings of sperm and micro-organisms. This fascinating 500-page document didn’t show up until 2006, when it was discovered in a dusty cabinet.