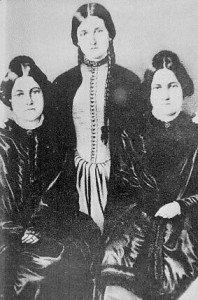

On April 1, 1848, modern Spiritualism was born in Hydesville, New York. That day, teenage sisters Margaret and Kate Fox announced that they had communicated with the spirit of a man who had been murdered in their house years before. A report of the incident first appeared in the New York Tribune, and it was reprinted soon after in both American and European newspapers.

Spiritualism Takes Hold in England

The Fox Sisters

The roots of Spiritualism stretch back to the eighteenth-century works of Emmanuel Swedenborg. But the incident with the Fox sisters ignited unprecedented interest in the phenomenon of communicating with the dead. Spiritualism would enrapture leading thinkers of the day, along with celebrated authors like Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Meanwhile, Charles Dickens came out as a staunch opponent–despite his own interest in the also-questionable practice of mesmerism.

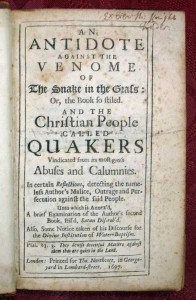

Spiritualism in its modern form emerged in Britain in 1852. That year, Maria Hayden traveled to London and offered her services as a medium. She conducted seances, complete with table rappings and automatic writing. But Spiritualism was far from new in England; Queen Victoria herself had subscribed to the belief as early as 1846. By the 1860’s Spiritualism had exploded into a full-fledged counterculture; it had its own newspapers, societies, treatises, and pamphlets. Seances–complete with table tapping, table tipping, automatic writing and levitation–were conducted in even the most genteel social circles.

Victorian England was ripe for just such a movement. Though it was an era of great scientific discovery, it was also an era of turning away from organized religion and confronting uncertainty. To fill the void, many Victorians turned to the supernatural, mesmerism, electro-biology, Spiritualism, and other relatively new pursuits. These new practices thoroughly blurred the lines between religion and science, and even proponents of Spiritualism were divided about how to characterize it.

From Fiction Writer to Leading Spiritualist

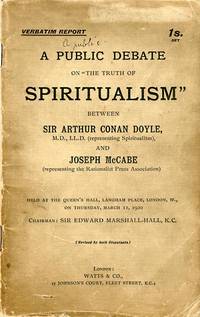

Elizabeth Barrett Browning famously subscribed to Spiritualism, much to the chagrin of her skeptical husband, Robert Browning, who was dragged to seances with her on multiple occasions. But the Brownings were far from the only authors at the seance tables; Christina Rosetti, John Ruskin, William Makepeace Thackeray, and Rudyard Kipling participated in seances. But it was Sir Arthur Conan Doyle who would delve so deeply into Spiritualism, he would turn away from fiction almost altogether.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning famously subscribed to Spiritualism, much to the chagrin of her skeptical husband, Robert Browning, who was dragged to seances with her on multiple occasions. But the Brownings were far from the only authors at the seance tables; Christina Rosetti, John Ruskin, William Makepeace Thackeray, and Rudyard Kipling participated in seances. But it was Sir Arthur Conan Doyle who would delve so deeply into Spiritualism, he would turn away from fiction almost altogether.

Conan Doyle encountered Spiritualism as early as 1866, thanks to a book by US High Courts Judge John Worth Edmonds. The judge, who claimed he’d communicated with his wife after she died, was one of the most influential Spiritualists in America. Conan Doyle was by now already famous as the creator of Sherlock Holmes. But he hoped to be remembered for something entirely different, so he turned away from his famous protagonist to study Spiritualism. Conan Doyle presented his first public lecture on Spiritualism in 1917, and he would eventually travel throughout Great Britain, Europe, and America educating audiences about the practice. He even trekked to Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa in the name of Spiritualism.

While Conan Doyle was respected in Spiritualist circles, his blind devotion led him headlong into ridicule on more than one occasion. He was taken in by Frances Griffith and Elsie Wright’s forged photographs of fairies. Conan Doyle, accepting the photographs as authentic, wrote a few pamphlets and The Coming of Fairies (1922), which made him a bit of a laughingstock. Later, Conan Doyle invited his friend Harry Houdini to attend a seance,with his wife Jean, acting as medium. Jean claimed to have contacted Houdini’s mother and “automatically” wrote a long letter in English. Unfortunately Houdini’s mother had known little English. Consequently the famous magician publicly declared Conan Doyle a fraud.

While Conan Doyle was respected in Spiritualist circles, his blind devotion led him headlong into ridicule on more than one occasion. He was taken in by Frances Griffith and Elsie Wright’s forged photographs of fairies. Conan Doyle, accepting the photographs as authentic, wrote a few pamphlets and The Coming of Fairies (1922), which made him a bit of a laughingstock. Later, Conan Doyle invited his friend Harry Houdini to attend a seance,with his wife Jean, acting as medium. Jean claimed to have contacted Houdini’s mother and “automatically” wrote a long letter in English. Unfortunately Houdini’s mother had known little English. Consequently the famous magician publicly declared Conan Doyle a fraud.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Conan Doyle persisted, remaining an avid Spiritualist until his death. Once he passed away, claims surfaced that he and his wife had arranged for communication from beyond the grave. On July 7, 1930, five days after Conan Doyle’s death, a seance was held at Royal Albert Hall. The presiding medium, Estelle Roberts, claimed that she’d relayed a message from Conan Doyle to his wife…but was drowned out by the overzealous organ player.

Dickens Ridicules Spiritualists

Although Conan Doyle was devoted to Spiritualism, he was careful not to sully Sherlock Holmes with such a controversial ideology. Thus whenever Holmes encounters potentially supernatural phenomena, he remains nonplussed and seeks a rational explanation. After all, as the famed detective says in “The Adventure of the Sussex Vampire,” “This agency stands flat-footed upon the ground, and there it must remain. The world is big enough for us. No ghosts need apply.” Charles Dickens would surely have agreed.

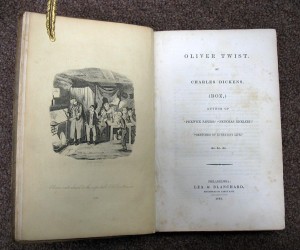

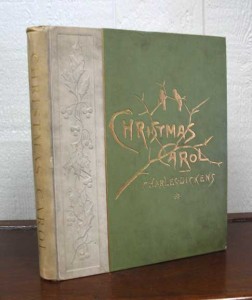

Dickens grew up reading penny weeklies like The Terrific Register, which he said “frightened the very wits out of [his] head.” The register’s pages brimmed with tales of ghosts, murder, incest, and cannibalism. Meanwhile, the English tradition of telling ghost stories at Christmas–coupled with Dickens’ own (lucrative) habit of publishing new stories at Christmas resulted in Dickens’ publishing plenty of ghost stories of his own.

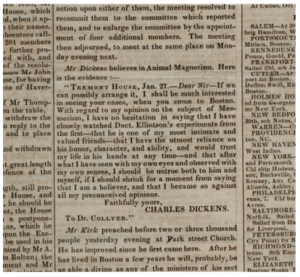

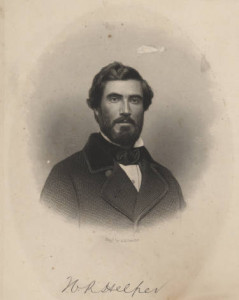

Dickens called Eliotson “one of my most intimate and valuable friends” in this letter to ‘The Boston Morning Post.’

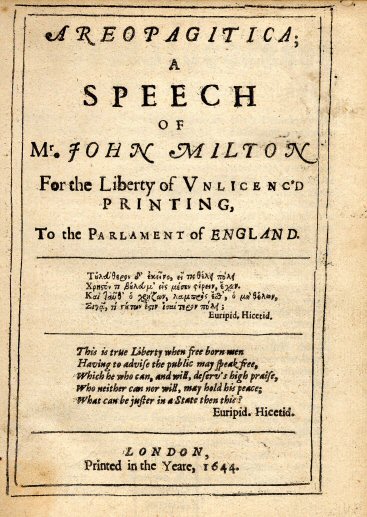

That didn’t stop the Inimitable from openly dismissing Spiritualism as unmitigated quackery. He frequently attacked Spiritualists in both Household Words and All the Year Round. In “Well Authenticated Rappings,” (Household Words, 1858), Dickens questions why spirits would return to communicate with the living, only to make idiots of themselves by tapping out banal messages rife with orthographical mistakes.

Yet even Dickens got pulled into a movement of highly questionable validity: mesmerism. Named for its creator, Anton Mesmer, mesmerism was the belief that the universe was full of an invisible magnetic fluid, which influenced all life and could be manipulated more easily with magnets. Prominent doctor John Eliotson was one of the leading proponents of mesmerism (also known as magnetism and animal magnetism). Eliotson was eventually shunned from the medical establishment as a result.

Dickens actually became a practicing mesmeric doctor, successfully putting both his wife and sister-in-law into a trance. During his family’s trip to Italy in 1844, Dickens also mesmerized the alluring Augusta de la Rue, who suffered from, as she called it, a “burning and raging” in her head. The attention he lavished on M. de la Rue was sufficient to evoke jealousy from Dickens’ wife, Catherine. Meanwhile, Dickens was less successful in his attempt to mesmerize his friend Charles Macready.

Dickens and his fellow mesmerists believed, as Eliotson did, that the practice represented a genuine improvement in the field of medicine–unlike Spiritualism, which served no such therapeutic function. Thus he felt perfectly justified in lambasting Spiritualism while simultaneously espousing a practice that, as modern readers, we might find laughable.

Dickens and his fellow mesmerists believed, as Eliotson did, that the practice represented a genuine improvement in the field of medicine–unlike Spiritualism, which served no such therapeutic function. Thus he felt perfectly justified in lambasting Spiritualism while simultaneously espousing a practice that, as modern readers, we might find laughable.

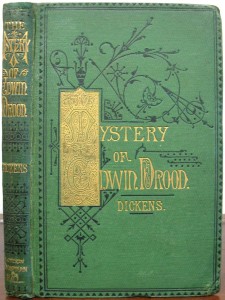

Ironically enough, Dickens was a frequent target of mediums. His final, unfinished novel, The Mystery of Edwin Drood has inspired many an author to attempt its end. But in 1873, printer Thomas James penned an ending for the book. He claimed that Dickens had dictated the ending from beyond the grave, calling the book The Mystery of Edwin Drood (Complete). Part second of The Mystery of Edwin Drood. By the spirit-pen of Charles Dickens, through a medium.

Ultimately both Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Charles Dickens illustrate the Victorian predilection for the supernatural and strange.

Related Posts:

Why Did Charles Dickens Write Ghost Stories for Christmas?

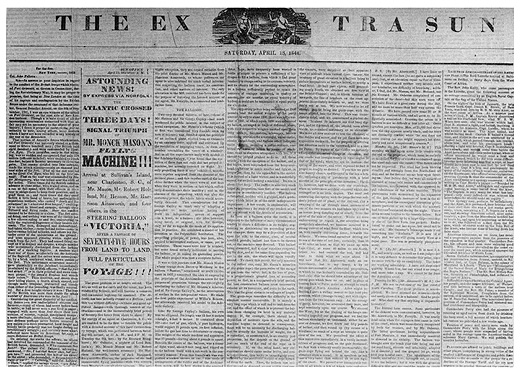

The Six Hoaxes of Edgar Allan Poe

All Posts-Charles Dickens

Thanks for reading! Love our blog? Subscribe via email (right sidebar) or sign up for our newsletter--you’ll never miss a post.

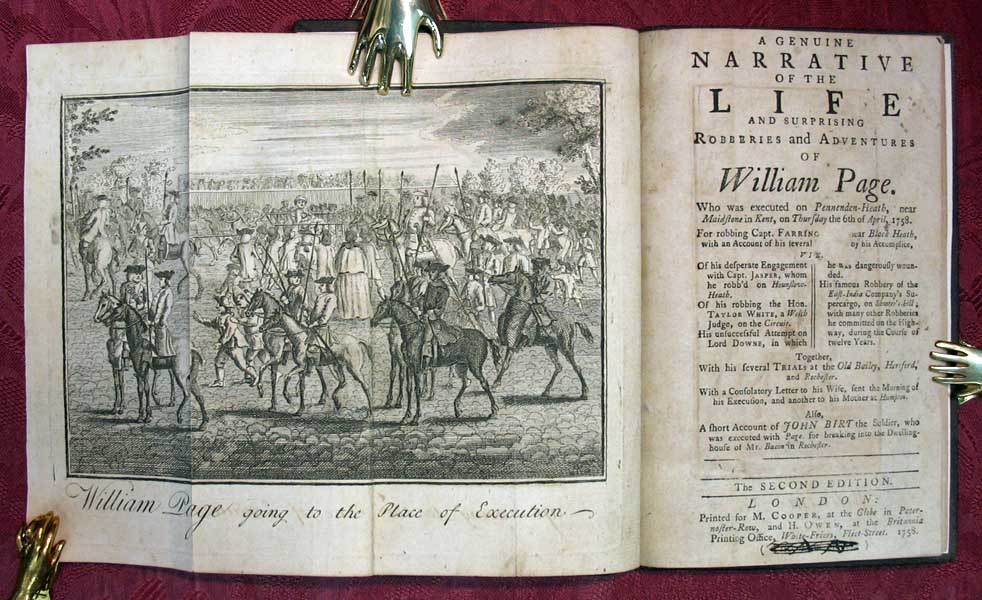

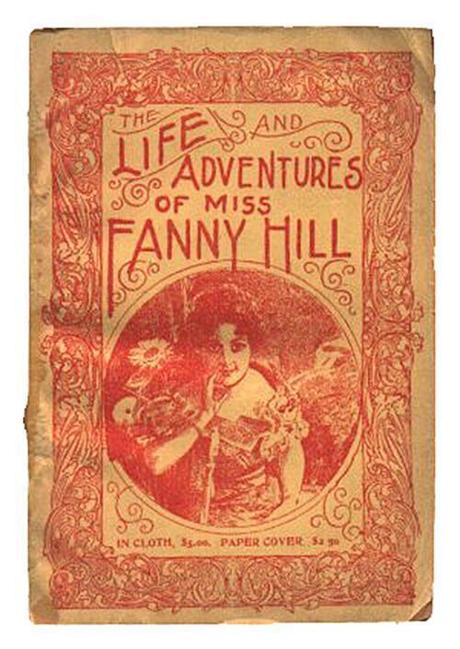

Considered the first pornographic novel published in English, Fanny Hill is every bit as lurid as one would expect from the fictional memoir of a Georgian prostitute. Even more scandalous: the eponymous protagonist enjoys the work of earning “profit by pleasing.” Author John Cleland and the book’s original publisher were immediately thrown into jail after the book was published. And in America, Fanny Hill was the subject of the country’s very first obscenity trial: in 1821, two men were charged with printing an illustrated version. That edition and subsequent contraband editions became hot collector’s items; even Benjamin Franklin was said to have a copy. The book found its way back to the US Supreme Court in 1963 after Massachusetts banned the book. The Supreme Court found the book lewd–and ruled that it was protected by the First Amendment.

Considered the first pornographic novel published in English, Fanny Hill is every bit as lurid as one would expect from the fictional memoir of a Georgian prostitute. Even more scandalous: the eponymous protagonist enjoys the work of earning “profit by pleasing.” Author John Cleland and the book’s original publisher were immediately thrown into jail after the book was published. And in America, Fanny Hill was the subject of the country’s very first obscenity trial: in 1821, two men were charged with printing an illustrated version. That edition and subsequent contraband editions became hot collector’s items; even Benjamin Franklin was said to have a copy. The book found its way back to the US Supreme Court in 1963 after Massachusetts banned the book. The Supreme Court found the book lewd–and ruled that it was protected by the First Amendment.