“I am Richard II. Know ye not that?”

So spoke Queen Elizabeth I to William Lambarde in August 1601–or so the story goes. The queen’s allusion to Shakespeare’s Richard II has long served as an illustration of the intense connection between arts and politics in Elizabethan England.

A Trusted Record Keeper

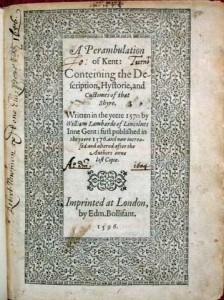

Born in London, William Lambarde was a noted antiquarian, barrister, and politician who likely served in Parliament. Lord Chancellor Sir Thomas Egerton appointed Lambarde Keeper of the Rolls in 1597, and Queen Elizabeth appointed him Keeper of the Records of the Tower in 1601. By this time, Lambarde was already quite well known for his A Perambulation of Kent. This volume, known as the first county history, was circulated in manuscript before it was printed in 1576. It was popular enough to go through several editions. Indeed, the last edition was published in 1656, some eighty years after its first appearance.

Born in London, William Lambarde was a noted antiquarian, barrister, and politician who likely served in Parliament. Lord Chancellor Sir Thomas Egerton appointed Lambarde Keeper of the Rolls in 1597, and Queen Elizabeth appointed him Keeper of the Records of the Tower in 1601. By this time, Lambarde was already quite well known for his A Perambulation of Kent. This volume, known as the first county history, was circulated in manuscript before it was printed in 1576. It was popular enough to go through several editions. Indeed, the last edition was published in 1656, some eighty years after its first appearance.

So how did the author of such a charming and innocuous work come to be at the center of political intrigue? Lambarde’s role as the Keeper of the Records of the Tower gave him unique access to records that spanned Elizabeth’s entire reign–and before. Early in August 1601, Lambarde presented Elizabeth with a book of “pandects,” the broad name for a compendium on virtually any subject. This book of pandects was a special compilation of records that Lambarde had prepared especially for Elizabeth.

Questions of Provenance and Authenticity

The ensuing dialogue between Lambarde and Queen Elizabeth I was recounted in a document titled “That which passed from the Excellent Majestie of Queen ELIZABETH, in her Privie Chamber at East Greenwich, 4 August, 1601, 43 reg. sui, towards William LAMBARDE.” Elizabeth supposedly told Lambarde, “I am Richard II. Know ye not that?” as she perused–and praised–Lambarde’s gift. The comment shows that Elizabeth knew that she, like Richard II, sat in a precarious position, in danger of losing her power at any moment.

At least, that was the conventional interpretation. But in recent years, scholars have questioned both the veracity of the document and the real implications of the statement. The document itself is first extant in 1780, where it’s included as an appendix to John Nichol’s biographical sketch of Lambarde in Bibliotheca Topographica Britannica. It was reprinted in 1788 in Progresses and Public Processions of Queen Elizabeth. Nichols added a note in a later edition that it was “communicated from the original, by Thomas Lambarde of Sevenoak, Esq.”

But the original author of the statement has been difficult to determine. The account drops to first person at the end, indicating that Lambarde may have written the account himself. He remained a competent and enthusiastic writer to the end of his life, and the manuscript could plausibly have passed down through multiple generations. Meanwhile, Queen Elizabeth was indeed on Greenwich on the date in question. Lambarde’s post as record keeper and independent interest in antiquities lend further support to the document’s authenticity. Thus it seems likely that the conversation happened as reported, even if we cannot readily identify the reporter.

Uncertain Succession

Elizabeth’s comment was certainly a pregnant one. She knew that her hold on the throne was loosening against her will. For years, there had been whispers about who would succeed her since she had no direct descendents. Many favored the succession of James VI of Scotland. Alternatives were Isabella of Spain, the sister of Spanish king Phillip III; and Arabella Stuart, the granddaughter of Margaret Tudor.

The majority of Elizabeth’s subjects were religiously moderate and would accept a monarch of either Catholic or Protestant persuasion, so long as tolerance was extended to observers of the other denomination. Elizabeth herself refused to discuss the matter and was careful not to show favor to any single heir. The entire situation invited intrigue upon intrigue, as various factions sought to assure the succession of their preferred candidates.

Essex Proves a Royal Disappointment

One such schemer was Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex. Elizabeth thoroughly enjoyed Essex at court but never deigned to admit him to her confidence; she knew that Essex was not to be trusted. In 1598, the English sent a large force to Ireland to oppose Hugh O’Neill, Earl of Tyrone. Essex was put in charge of the effort and granted sweeping administrative power in Ireland.

However, Essex failed miserably, refusing to engage O’Neill and his men even under direct orders from the queen. When pushed harder, Essex struck an accord with O’Neill. Although the exact details of their agreement are unknown, scholars generally agree that they probably pledged their mutual support of James VI of Scotland.

The queen, none too pleased with this arrangement, reproached Essex–who responded by deserting his post, sailing for England, riding to Greenwich, and bursting in on the queen to beg her mercy. Queen Elizabeth was unconvinced. She banished Essex from her presence, and he was arrested later that day. Essex served a year of house arrest and emerged to discover that support for his cause had evaporated. All the while, his rival Robert Cecil had continued his own efforts to ingratiate himself to the queen.

A Failed Rebellion

Essex was sure that he’d still be able to garner support. His first move was to sponsor a performance of Shakespeare’s Richard II. He believed that the parallels would be quite clear: like Richard II, Queen Elizabeth had availed herself of malevolent advisors (ie, Cecil) and would invariably and imminently lose the throne. Such a move might seem ridiculously subtle by today’s standards, but the comparison would not have been lost on Essex’s contemporaries.

Essex then gathered about 300 followers and tried to persuade his replacement in Ireland, Lord Mountjoy, to bring his troops back to support Essex. Cecil already knew what Essex was planning, and Queen Elizabeth sent four advisors to Essex’s home. Essex locked them in his library and took to the streets, presuming that he’d be able to raise a supportive mob. He also hoped that the Sheriff of London, Sir Thomas Smyth, would support his cause.

Yet Smythe blew him off, and the mob failed to materialize. The Earl of Nottingham led a force of men to Essex house and forced Essex to surrender. He was tried and found guilty of treason alongside the Earl of Southampton (a patron of Shakespeare and the dedicatee of Venus and Adonis and The Rape of Lucrece). While Southampton was thrown into the Tower of London, Essex was sentenced to death. He hoped that Queen Elizabeth would intercede. She did not, and Essex was executed on February 25, 1601.

Seditious Shakespeare

The performance of Richard II was considered so treacherous that the Chamberlain’s Men also came under suspicion of sedition. On February 8, 1601, spokesman Augustine Philips testified, eager to distance the players from the performance. He emphasized that none of the players had wanted to perform such an outdated play, but that Essex had paid them 40 shillings above the usual fee. The players were exonerated and even performed for Elizabeth at Whitehall on the eve of Essex’s execution.

Some experts argue that the speed with which the investigate against the players was dropped shows how politically insignificant Shakespeare’s play really was. Others believe the play a sort of anthem for the Essex camp; it addresses issues of chivalry, pragmatism, and the divine right of monarchs. And it’s also possible that Essex didn’t intend treason at all, but that he was merely desperate to alert the queen of Cecil’s intentions. At any rate, the fact that Shakespeare’s imagined rebellion was implicated in a real one exemplifies the interplay between arts and literature in Elizabethan England.

Though William Lambarde was a trusted advisor to Queen Elizabeth I, his influence would not extend to the end of her reign. Lambarde passed away only a few months after his apocryphal exchange with Elizabeth. The episode elucidates Lambarde’s unique place in Elizabethan history, as much more than an author of a quaint county history.

Related Posts:

Happy Birthday, William Shakespeare!

Meet Dr. Erin Blake, Curator of Art and Special Collections at the Folger!

Thanks for reading! Love our blog? Subscribe via email (right sidebar) or sign up for our newsletter--you’ll never miss a post.